The Pitfall of High Expectations and Disillusionment

Lesson 8

Lesson 8: The Pitfall of High Expectations and Disillusionment

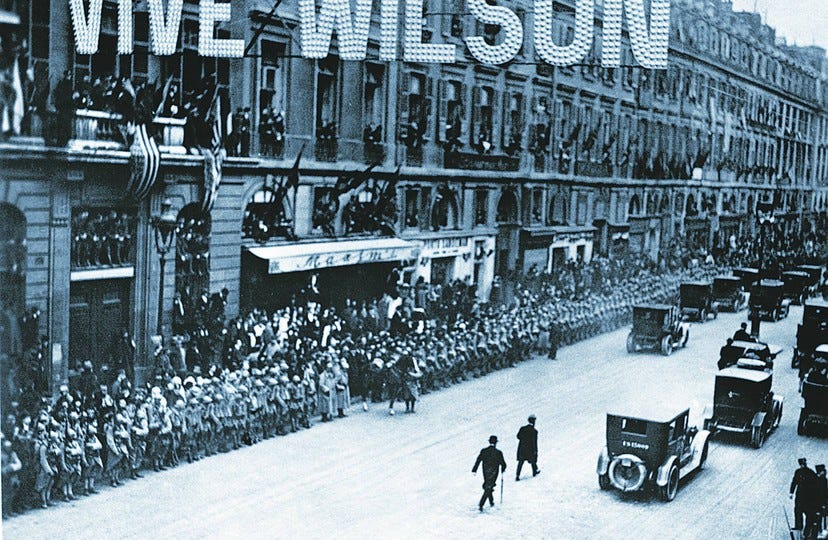

When Woodrow Wilson landed in the harbor of Brest on the French Atlantic coast on Friday, 13 December 1918, the city’s mayor welcomed him at the dock as an apostle of liberty—a liberator come to free the peoples of Europe from their suffering.

The very next morning, Wilson drove through the streets of Paris, cheered by massive crowds lining the boulevards. The French press, across all political affiliations, hailed him as “the incarnation of the hope of the future.” Similar scenes played out in England and Italy in the weeks that followed, where Wilson was greeted not as a mere diplomat, but as a world savior.

Along his motorcade route in Paris, giant letters lit up above the street in white lightbulbs: Vive Wilson — Long live Wilson. The atmosphere was euphoric, verging on the surreal. The British writer H. G. Wells later captured the essence of this moment, describing the intensity—and fragility—of Wilson’s apotheosis:

“For a brief interval, Wilson stood alone for mankind. And in that brief interval there was a very extraordinary and significant wave of response to him throughout the earth… He ceased to be a common statesman; he became a Messiah.”

Yet for all the soaring rhetoric and ecstatic adoration, Wilson’s triumph was tragically short-lived. Today, his reception in Europe is remembered less as a turning point than as an ironic footnote to the Great War. The immense hopes he inspired unraveled almost as quickly as they were raised. The reverence once shown toward the American president across Europe and beyond gave way to disappointment, then to resentment.

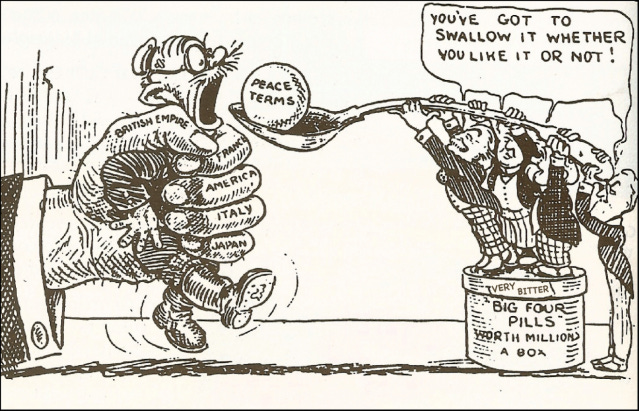

The Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, 1919, fell far short of the aspirations Wilson had stirred. It was condemned not only by former admirers around the world, but also by Wilson’s own country. The U.S. Senate refused to ratify it, and the American public, weary of foreign entanglements, retreated into the comforting embrace of what Warren Harding would soon call “normalcy.”

Where did the overstrain of 1919 lie? Several factors combined.

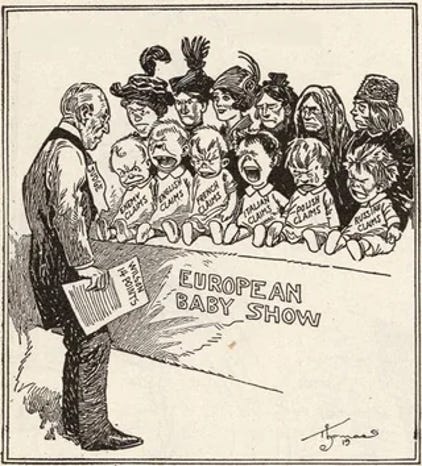

First, the sheer scale. Wilson’s vision of transparent, expert, law-based diplomacy drew two dozen official delegations — including Britain’s dominions — and countless unofficial groups from India, Egypt, and elsewhere. Over 10,000 delegates, advisors, and assistants filled Paris. Committees soared into the dozens, plenaries exceeded 1,000 participants, and the city swarmed with activists.

Second, the media glare. Hundreds of journalists carried hopes and outcomes across continents — and their home audiences’ reactions fed back into the conference in real time. It was the first truly global, media-infused peace process.

Third, the issues themselves. Unlike 1815, 1919 confronted problems that redrawn borders couldn’t solve: millions of refugees, prisoners of war, and newly stateless people. The war’s hopes had crystallized into two global watchwords — “the war to end all wars” and “self-determination.”

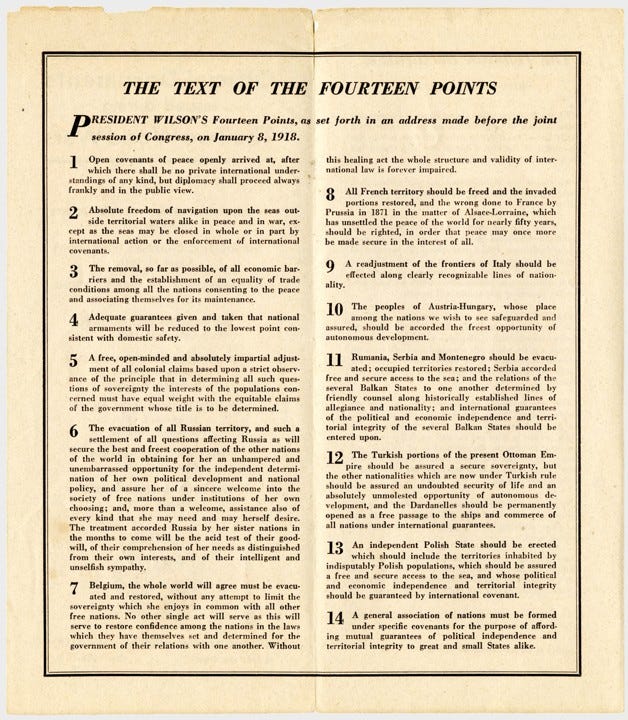

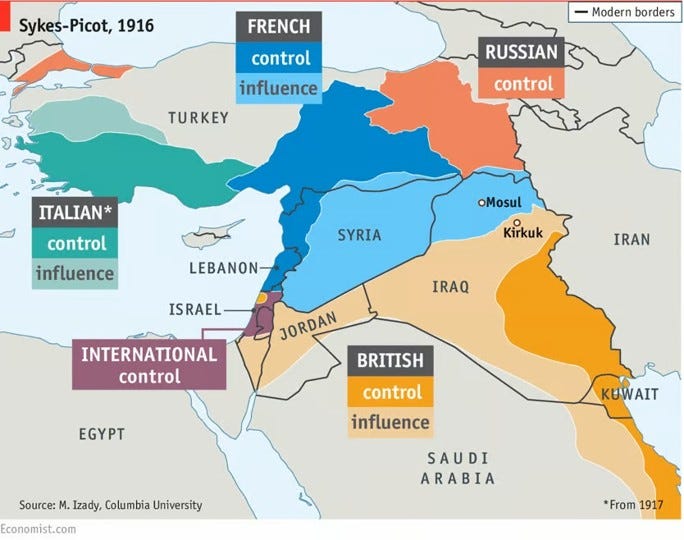

Wilson’s Fourteen Points gave self-determination its moral force. But the world wasn’t ready for it. On his November 1918 voyage to Europe, he privately confessed his fears to George Creel, America’s propaganda chief:

“Have you not unconsciously woven a net from which there is no escape for me? The whole world now looks to America with all its hopes and burdens. All these expectations contain a dreadful urgency… People endure their tyrants for years, but they tear their liberators to pieces if the millennium is not created at once.”

The Burden of High Expectations from “Self-Determination” for European Colonies

There is, of course, a vast historiography on the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 and the role played by the United States. Yet much of it remains narrowly focused on Europe — particularly on the policies, decisions, and personalities of the Great Powers: Britain, France, Italy, and the United States.

In fact, much of the literature closely mirrors the priorities of the “Big Four” at the negotiating table. The depth of analysis on specific issues and regions often correlates directly with the degree of attention those matters received from Allied leaders at the time. This is understandable. Many of the debates in Paris concerned matters of enormous consequence — both for the immediate shape of the postwar European order and for the longer trajectory of the twentieth century.

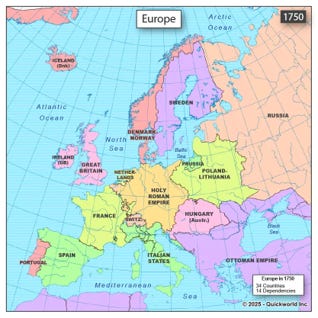

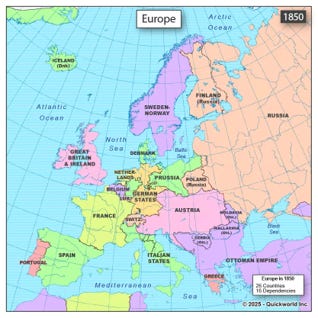

Territorially, the most dramatic revision was the disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In its place emerged a patchwork of new or expanded states: Austria and Hungary became independent nations; Czechoslovakia was created; Romania and Serbia were enlarged, with the latter forming the nucleus of a new multinational kingdom — Yugoslavia — which now included Croatia, Bosnia, and Slovenia.

The most disastrous and, arguably, most avoidable revision at Versailles was the deliberate humiliation of the German Empire. Territorial losses — most notably the creation of an independent Poland carved partly from acient Prussian lands — were compounded by crippling reparations. The final demand, set at approximately US$33 billion in 1921 dollars (equivalent to $600–760 billion today), inflicted deep economic wounds.

National humiliation followed, feeding the narrative of betrayal at home and giving birth to the Dolchstoßlegende — the “stab-in-the-back” myth that claimed Germany had been defeated not on the battlefield, but by treachery on the home front. Hyperinflation, political instability, and resentment cascaded in the following years, laying the groundwork for Hitler’s rise and the eventual descent into another global war.

Beyond Central Europe and the colonial world, the collapse of the Russian and German empires redrew the map of northeastern Europe. Finland, which had been conquered by Tsar Alexander I in 1809 and turned into an autonomous Grand Duchy within the Russian Empire, declared independence in 1917 amid the chaos of the Bolshevik Revolution. Its sovereignty was secured through a brutal civil war and the repulsion of Soviet forces during the Finnish War of Independence and again during the Winter War in World War 2.

The Baltic states — Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania — followed a similar path, asserting independence as imperial authority crumbled. These were not simply new nations born from Versailles, but heirs to much older histories. Lithuania, in particular, traced its identity to the long-standing Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which had once stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea. The resurrection of Poland itself after over a century of partitions was rightly celebrated — but it reopened border disputes with Lithuania and Ukraine, and rekindled old rivalries. In this northeastern corner of Europe, as elsewhere, Versailles ratified change it did not control — and left behind new fault lines.

This European core of the Versailles failure is well understood — and as I’ve discussed in earlier Substacks here and here, it has been picked apart and analyzed from nearly every angle.

What is far less often remembered, however, are the global repercussions of 1919.

Much like the Allied leaders at the time, international historians have tended to overlook the questions and demands that fell outside the immediate focus on Europe. In particular, the calls for self-determination from peoples across Asia, the Middle East, and Africa were largely ignored—whether by design or by indifference.

This neglect was no accident. The Great Powers had little interest in applying the principles of national sovereignty and self-rule to their own empires. Where the aspirations of colonized peoples—whether in China, Korea, Egypt, Tunisia, India, Indochina, or beyond—conflicted with the interests of the victors, those aspirations were simply excluded from the agenda.

Yet in the spring of 1919, resistance erupted across the non-European world. Anticolonial nationalism surged with a scope and intensity not seen before. A few international historians have acknowledged this in passing, recognizing 1919 as a critical moment in the emergence of global anticolonial consciousness. But the movements themselves—their demands, their disappointments, and their deep historical context—have rarely been given the attention they deserve in mainstream accounts of the Paris Peace Conference.

Versailles, then, was not merely a European settlement. It was a global rupture.

The peace collapsed under the weight of its own contradictions. Intended to end all wars, it instead produced a cascade of expectations—some idealistic, others cynical—so vast and so unevenly fulfilled that disappointment was not just likely, but inevitable.

Sykes-Picot Agreement and the Broken Promise of Self-Determination

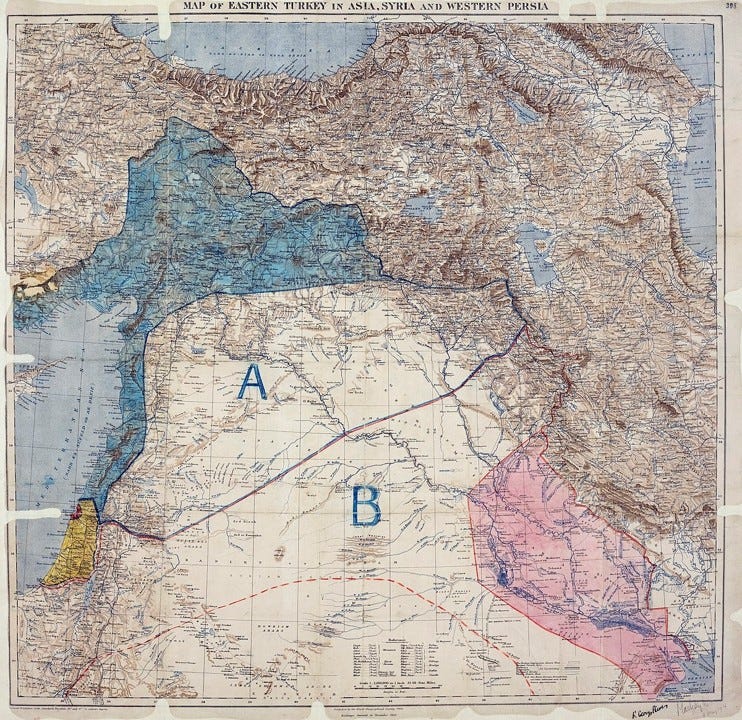

The modern frontiers of the Arab world only vaguely resemble the blue and red grease-pencil lines secretly drawn on a map of the Levant on 16 May 1916, at the height of the first world war.

Sir Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot were appointed by the British and French governments respectively to decide how to apportion the lands of the Ottoman empire, which had entered the war on the side of Germany and the central powers.

The Russian foreign minister, Sergei Sazonov, was also involved. The Allies agreed that Russia would get Istanbul, the sea passages from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean, and Armenia; the British would get Basra, Hafia and southern Mesopotamia; and the French a slice in the middle, including Lebanon, Syria and Cilicia (in modern-day Turkey). Palestine would be an international territory.

In between the French- and British-ruled blocs, large swathes of territory, mostly desert, would be allocated to the two powers’ respective spheres of influence. Italian claims were added in 1917. But after the defeat of the Ottomans in 1918 these lines changed markedly with the fortunes of war and diplomacy.

In 1919, a famous Arab delegation came to Paris, with Prince Faisal and T. E. Lawrence. Politically, however, the outcome was that the Arabs did not receive the pan-Arab state they hoped for, because the reality of the Middle East was shaped by Britain and France, who, as in Asia and Africa, divided territories between themselves. In 1916, through the infamous Sykes–Picot Agreement, they had literally drawn borders with thick markers on maps and allocated these areas to themselves.

A pan-Arab state did not exist in 1919, nor later. In the long run, countless actors in the Middle East referred back to this moment of 1919, arguing that the Arabs had been denied the right of self-determination. Sykes-Picot has become a byword for imperial treachery.

George Antonius, one of the first historians on Arab nationalism, called it a shocking document, the product of “greed allied to suspicion and so leading to stupidity.” It was, in fact, one of three separate and irreconcilable wartime commitments that Britain made to France, the Arabs and the Jews. And it collided squarely with Woodrow Wilson’s principle of self-determination.

The resulting contradictions have been causing grief ever since. Nasser in Egypt in the 1950s referred to it, later Saddam Hussein invoked it when invading Kuwait, Gaddafi referred to it as well, and even the so-called Islamic State (ISIS) in 2016 unfurled a large banner in the Syrian desert declaring: “Here ends Sykes-Picot.”

Independence for Indochina and Ho Chi Minh’s Broken Hopes

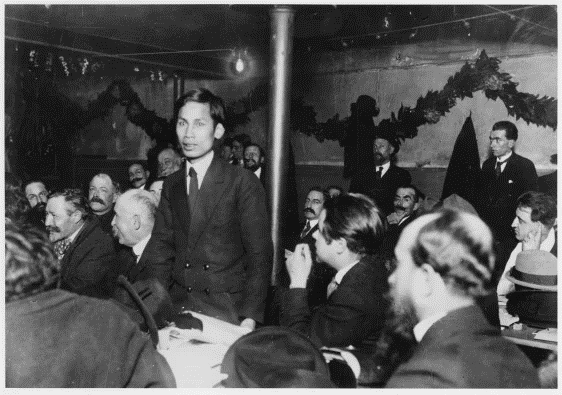

Another young man who appeared in Paris in 1919 was Nguyễn Ái Quốc — later known as Ho Chi Minh. He too wanted to invoke the principle of self-determination, demanding the independence of Indochina.

He wanted the approximately 250,000 Indochinese soldiers who had fought for France not to be treated worse than French recruits. Of course, he was brusquely and immediately dismissed by a mid-level French official — told that France’s colonies were not on the agenda.

Ho Chi Minh was humiliated, his hopes shattered. Seeking justice, he turned to socialist and communist circles, eventually joining the French Communist Party in 1920.

The irony is stark: the man who once appealed to Wilson’s American principle of self-determination would decades later lead Vietnam into wars first against France and then — against the United States itself.

Communist China and Today’s Trade War

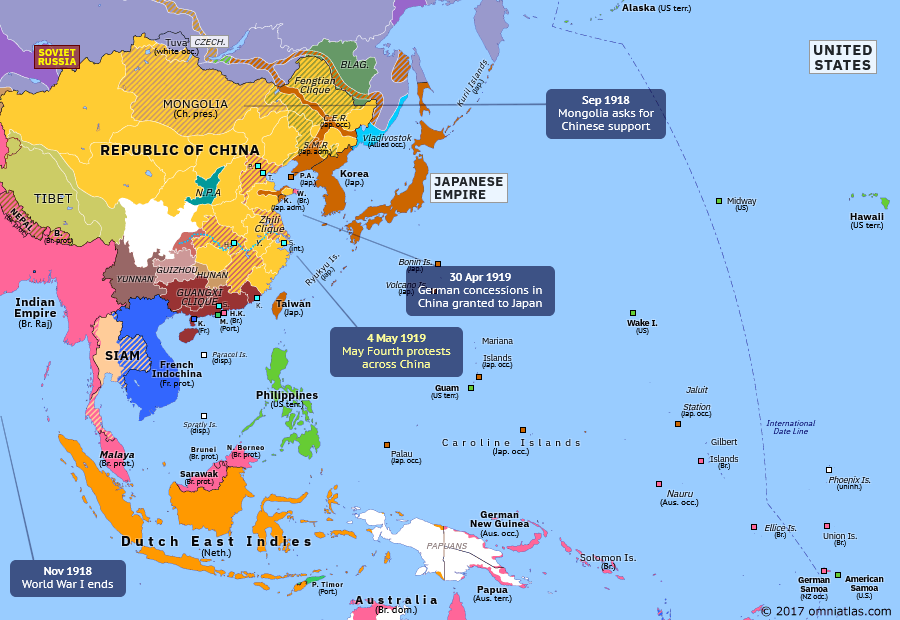

In May 1919, huge demonstrations erupted in China. In Chinese political culture, this event, the “May Fourth Protest,” is still remembered as a decisive turning point. They linked to it the hope that the semi-colonial status of China, dating back to the Opium Wars — with treaty ports such as Hong Kong or Shanghai — would come to an end. In November 1918, demonstrators in Shanghai carried placards in Latin letters reading: “The world must be made safe for democracy.”

But in the summer of 1919, these hopes collapsed when the Treaty of Versailles stipulated that Germany’s former concessions in China would not return to China but would go instead to Japan as spoils of war.

Hundreds of thousands of Chinese protested against this “betrayal of the principles of national self-determination.” China ultimately did not sign the Treaty of Versailles. The Chinese delegation broke off its participation.

Mao Zedong himself took part in these demonstrations. He interpreted the experience of failed peace as proof that China must find its very own path — not a mere imitation of Western modernization, not liberal internationalism, but a specifically Chinese way.

In a way, today’s trade war is a direct consequence of the heightened expectations set at the Versailles Treaty which created Communist China — with all its woes such as its planning economy, resulting in systematic over-capacity as we explained in our China series extensively.

The Nuclear Arms Race: From Fission to MAD

The dawn of the nuclear age was not American, but German.

In December 1938, Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann succeeded in splitting the uranium atom in Berlin. Lise Meitner and her nephew Otto Frisch, both in exile from Nazi Germany, interpreted the results correctly: this was nuclear fission. The discovery was published in a scientific journal, and the implications were immediately obvious to physicists around the world. If the energy of the atom could be controlled, it could also be weaponized.

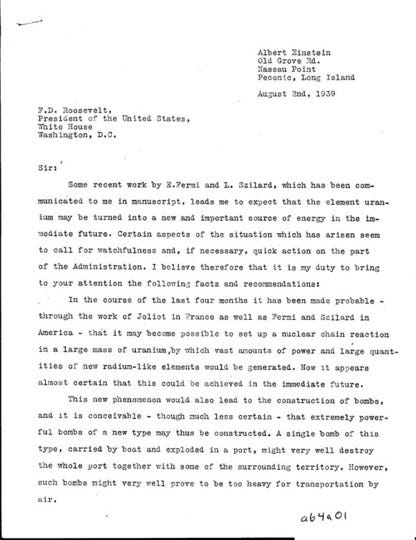

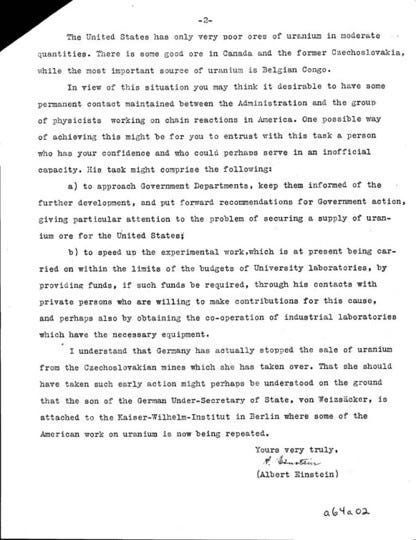

Alarm spread quickly. In America, a small group of émigré physicists — including Leó Szilárd and Edward Teller — feared that Hitler’s Germany might build the bomb first. They persuaded Albert Einstein, then the most famous scientist in the world, to lend his authority.

In August 1939, Einstein signed the now-famous letter to President Roosevelt, warning that Germany might develop “extremely powerful bombs of a new type.” Roosevelt took it seriously. Out of this fear was born the Manhattan Project.

Led by J. Robert Oppenheimer at Los Alamos, the project mobilized the best scientific minds, the vast industrial resources of the United States, and total wartime secrecy. Its motto was simple: build the bomb before Hitler does. By July 1945, the first atomic device was detonated in the desert of New Mexico. In August, Hiroshima and Nagasaki demonstrated to the world a new level of destructive power.

The United States briefly held the monopoly, but only briefly. The Soviet Union, aided by German engineers forcibly relocated to the USSR after the war, and by the espionage of Klaus Fuchs — a German-born physicist who had worked at Los Alamos and secretly passed critical knowledge to Moscow, as later uncovered by British intelligence — detonated its first atomic bomb in 1949. The monopoly was over. The nuclear arms race had begun.

Off To the Races

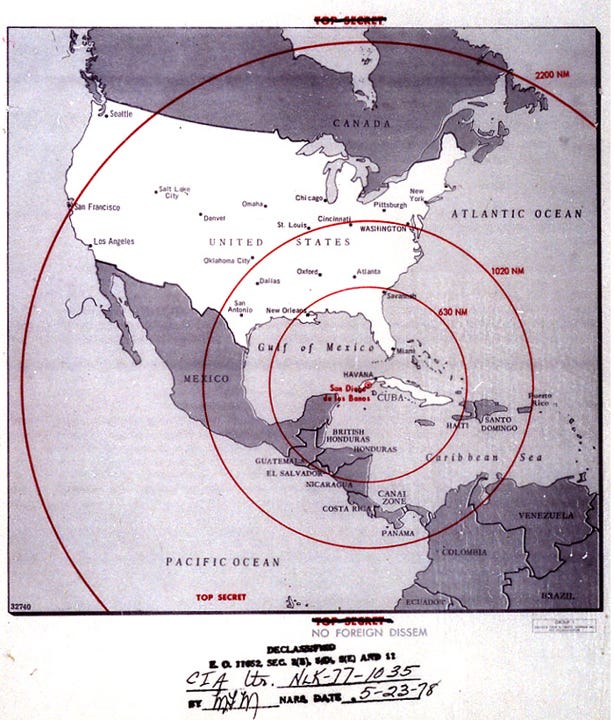

From then on, the arsenals expanded at a frenetic pace. By the early 1960s, both sides had enough warheads to destroy the planet many times over. And in October 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, the world came terrifyingly close to seeing it happen. For thirteen days, the United States and the Soviet Union stood on the edge of annihilation.

American forces were raised to DEFCON 2, everything that could fly or float was armed, and a single misstep could have ended civilization. When Khrushchev blinked and withdrew his missiles, the lesson was burned into the minds of both sides: the arms race had produced only madness.

Yet out of this madness came a form of maturity. President Kennedy openly sought more peaceful solutions. For a brief moment, “détente” — a policy of relaxation of tensions — dominated American politics.

It directly addressed the threat of nuclear war through a series of arms control treaties such as SALT I and II. Key achievements included the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and the Helsinki Accords in 1974.

The famous red telephone “hotline” was installed between Washington and Moscow to ensure that direct communication could take place and no misunderstanding spiraled out of control. Limited test-ban treaties followed. However cynically, both sides learned to manage risk.

But many risks persisted. Nuclear accidents — the so-called “broken arrows” — littered the Cold War record: bombs lost at sea, warheads jettisoned from planes, even live devices recovered by luck. Since 1950, there have been a total of 32 nuclear weapon accidents officially recorded — 32 too many.

One of the most dramatic was the Palomares Incident. In January 1966, a U.S. Air Force B-52 bomber collided mid-air with a refueling tanker over the village of Palomares in southern Spain, accidentally dropping four hydrogen bombs. Three were recovered on land within 24 hours — two of them having ruptured and scattered radioactive plutonium over the countryside. The fourth bomb plunged into the Mediterranean Sea, triggering one of the largest and most complex search operations in U.S. naval history. After an intensive 80-day effort, involving deep-sea submersibles and over 12,000 personnel, the missing bomb was finally located and retrieved from nearly 2,900 feet below the surface. Today, a small museum in Spain commemorates the incident as one of the starkest reminders of Cold War nuclear risk.

Brezniev the Madman — Reagan the Actor

But détente proved fragile. The spirit Kennedy had shared with Khrushchev never returned under the leaders that followed. Under Leonid Brezhnev, from 1964 to 1982, the lesson Moscow drew from Cuba was not to cooperate but to never again fall behind the United States in military capability.

Under Brezhnev, and later Yuri Andropov, the Soviets invaded Afghanistan and massively expanded their arsenal. By 1987, the Soviet Union held over 61,000 nuclear warheads — enough firepower to end the world dozens of times over.

Ronald Reagan was the fiercest critic of détente. He ran for the presidency on this very point, branding the Soviet Union the “evil empire.” His Strategic Defense Initiative — “Star Wars” — was born, at least on paper. Reagan’s vast build-up of nuclear deterrence in the 1980s, combined with the ruinous war in Afghanistan and the tragic nuclear accident at Chernobyl, pushed the Soviet economy to exhaustion. But it also pushed the world back to the edge.

Fun Fact: Reagon - the Actor

Reagan’s much-feared “Star Wars” never came close to being deployed. It was more concept than reality, a bold bluff dressed up as policy. While billions were earmarked for research, no operational system was ever built. Yet the psychological effect was enormous. The Soviets, already crippled by economic stagnation, poured scarce resources into countering a phantom shield. In that sense, SDI was less about lasers in space than about breaking the back of an empire on the ground.

In 1983, Cold War tensions reached their highest point since Cuba. The United States announced the deployment of Pershing II missiles in Europe and staged FleetEx ’83, the largest naval exercise yet in the Pacific. Andropov, already ill and deeply suspicious of Reagan’s intentions, feared a pre-emptive U.S. strike.

The Soviets launched Operation RYAN, a vast intelligence program designed to detect signs of an imminent American attack. That November, during NATO’s Able Archer exercise, Soviet radars mistook routine drills for the beginning of a nuclear strike. For days, Moscow’s leadership considered a pre-emptive response.

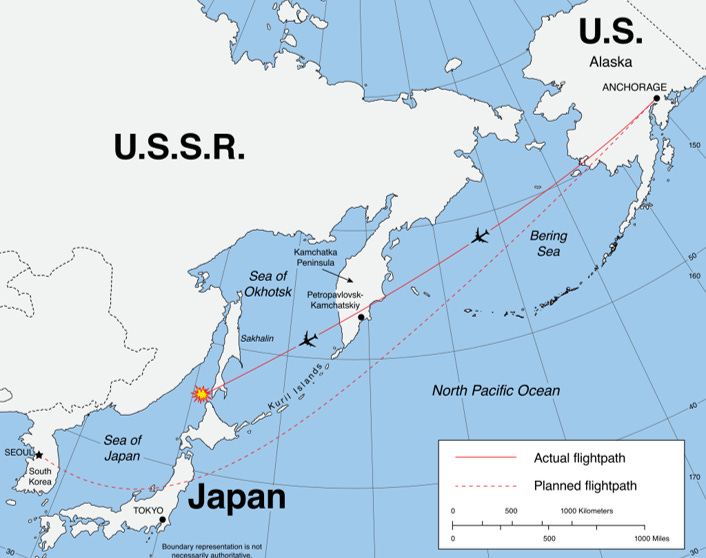

The crisis culminated in tragedy. On September 1, 1983, Soviet air defenses shot down Korean Air Lines Flight 007, a civilian 747 that had strayed into Soviet airspace. All 269 passengers and crew were killed, including U.S. Congressman Larry McDonald.

Then as now, the Politburo claimed it was a spy mission, a deliberate provocation by the United States. The U.S. accused the Soviets of obstructing rescue and suppressing evidence. The flight recorders were hidden until 1992. In response, President Reagan issued a directive that the U.S. Global Positioning System (GPS), then a military tool, would eventually be made freely available for civilian use worldwide — one of history’s most consequential peacetime legacies of a nuclear standoff.

And yet, paradoxically, from this insanity came stability. Mutually Assured Destruction — MAD — created an equilibrium of terror. By the mid-1980s, under Mikhail Gorbachev, both sides could openly admit what had long been obvious: any first strike would be suicide. It was peace by fear, stability through the certainty of annihilation. And with Gorbachev’s arrival in March 1985, nuclear de-armament truly began.

Would You Trade New York for Paris?

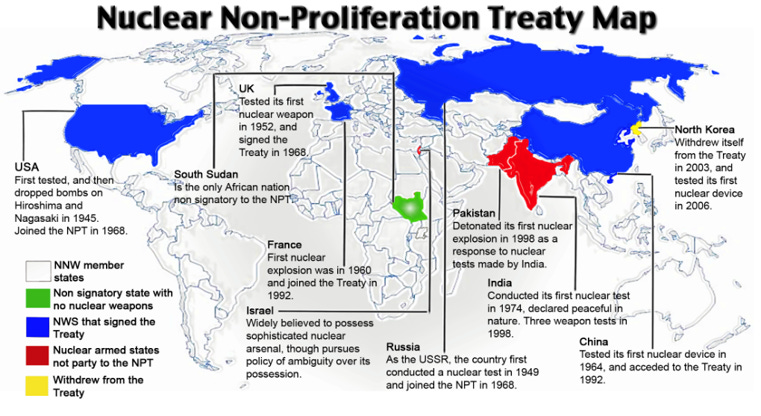

It was in this environment that the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) was born.

In a world where the U.S. and USSR already possessed enough firepower to destroy the world many times over, it was at least reasonable to prevent more players from joining the club. The NPT was not a moral gesture but a pragmatic one: it tried to freeze the nuclear hierarchy in place, stabilizing a fragile balance.

No one expressed the fragility of this arrangement more vividly than Charles de Gaulle. When President John F. Kennedy visited Paris in the early 1960s and urged him to rely on NATO and the American deterrent, de Gaulle cut him off with a devastating question: “Would you trade New York for Paris?”

With that one line, he exposed the central weakness of extended deterrence: no American president could ever be fully trusted to sacrifice an American city to save a European one and his question was as relevant then as it is now. For President de Gaulle, this was not rhetoric but survival. France would therefore build its own arsenal — and by 1960, it had tested its first nuclear device.

Other powers followed in short order. Britain had already joined the nuclear club in 1952. China tested in 1964. India followed in 1974, Pakistan in 1998, and North Korea in 2006. Israel, meanwhile, pursued a policy of deliberate “opacity”: it never admitted possession, never signed the NPT, but by the late 1960s had built an undeclared arsenal centered on the Dimona reactor. Its silence was itself a signal — everyone understood, and no one said so out loud.

For every nation that built, others could have and chose not to. Germany and Japan, both bound by their post-1945 settlements, lived under Washington’s umbrella. Sweden, which had a working program by the 1960s, dismantled it in 1972. Switzerland, too, quietly abandoned its designs. And Japan remains the world’s most striking case of “nuclear latency” — with vast plutonium stockpiles, advanced reactors, and sophisticated missile technology, it could build a bomb in months, yet has refrained for decades, trusting in American protection.

And then came the rarest case of them all: South Africa. In the 1980s, Pretoria secretly built six nuclear warheads, motivated by its isolation under apartheid and its fear of regional conflict. But by 1989, under President F. W. de Klerk, South Africa made the unprecedented decision to dismantle them all. By 1991 it had joined the NPT, and by 1993 it had invited the International Atomic Energy Agency to verify that every weapon and every document had been destroyed. It remains the only nation in history to build nuclear weapons and then voluntarily give them up.

This is the architecture of non-proliferation: one side promised protection, the other trusted that promise.

Since it was adopted more than 50 years ago, the NPT has been described as the cornerstone of international efforts to limit the danger of nuclear war, its preservation a key, shared policy objective of the P5 - the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council - namely the United States, Britain, France, Russia and China.

The NPT was conceived as a grand bargain between nations who did not have nuclear weapons and promised not to develop them and the P5, who did have them in 1968 and promised, in Article VI of the treaty, to undertake good faith negotiations to eliminate their nuclear arsenals.

But in the five decades since, these five nuclear-armed states have continued to insist that other signatories to the treaty honor their commitment not to build nuclear weapons, but they have never seriously considered meeting their obligations to disarm.

Tension over this blatant failure to uphold their end of the bargain has been growing for years and helped fuel the 2017 adoption by 121 non-nuclear-armed states of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, a new treaty consistent with Article VI and intended to pressure the countries that have nuclear weapons to meet their obligations to get rid of them.

The gap between the promises of the P5 and their behavior has grown into a chasm since the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Russia has made repeated threats to use nuclear weapons and NATO — representing France, the United Kingdom and the United States — has replied with nuclear threats of its own.

What is clear today is this: not only have the P5 failed to begin serious negotiations to eliminate their nuclear arsenals, as they promised decades ago — they will not even commit to refraining from starting World War III.

The NPT bargain, once hailed as a cornerstone of global stability, is now fraying at every seam. Russia openly threatens nuclear war. China expands its arsenal at an accelerating pace. In the United States, voters — weary of Iraq, Afghanistan, and mounting deficits (as we detailed in Lesson 7) — demand that allies shoulder a greater share of the defense burden. Allies, in turn, accuse Washington of unreliability; Washington counters with charges of free-riding. Mutual trust erodes.

And yet, as we’ve tried to show throughout, the truth is more complicated. These bargains were always mutual — built on expectations that were never entirely realistic, and shaped by political promises no side was ever fully prepared to keep. The disillusionment now coursing through both camps was embedded in the agreement from the beginning.

In many ways, we are no longer in the post–Cold War nuclear order. That chapter is over. What has emerged is something more unstable, more fragmented — and far less reassuring.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Project Sapphire

Careless nuclear testing across the Soviet Union during the Cold War left a profound mark on the people of Kazakhstan — so much so that they coined the term “nuclear neuralgia.” Between 1949 and 1989, nearly 500 tests, many atmospheric, were conducted at the Semipalatinsk test site, bathing local populations in radioactive fallout. Doctors who dared investigate the resulting health effects — hemorrhaging, blood disorders, congenital deformities — were silenced or ignored.

Their research was buried in classified military archives until Gorbachev’s glasnost reforms finally allowed the truth to emerge. This public health crisis triggered mass activism, crystallized in 1989 by the Nevada–Semipalatinsk movement, founded by poet Olzhas Suleimenov, which gathered millions of signatures demanding the test site’s closure.

Following the USSR’s dissolution, three newly independent states — Belarus, Ukraine and Kazakhstan — inherited vast Soviet-era nuclear infrastructure: warheads, missile launchers, bombers, and personnel — with little capacity to secure or maintain them.

Among these, Kazakhstan stood out in affirming, early on, its commitment to non-proliferation. President Nazarbayev declared the nation non-nuclear in principle, and in May 1992, Kazakhstan formally joined the NPT, reflecting both strategic outreach and pragmatic positioning toward Western integration.

Diplomatic reinforcement came from meetings with U.S. President George H. W. Bush and senators Sam Nunn and Richard Lugar. Western investment, especially in oil infrastructure, demanded clarity on non-proliferation. That environment paved the way for what remains one of America’s most successful non-proliferation initiatives:

With this background, Andy Weber, a US Foreign Service Officer (State Department) based in Kazakhstan, received a cryptic note from his car mechanic in 1994 reading — “600 kg, 90%” — referring to enough highly enriched uranium (90% U-235) for twenty bombs, stored insecurely at the Ulba Metallurgical Plant.

In a covert operation, U.S. and Kazakh teams carefully packed the uranium into 400 containers, loaded it onto C-5 transport planes, and airlifted it to Oak Ridge, Tennessee — all without incident, and without publicity. In return, Kazakhstan received $30 million in aid. Remarkably, the repurposed fuel went on to supply roughly 10% of U.S. civilian nuclear energy for an entire decade. Not a bad deal.

For the full story (and I highly recommend it), watch Turning Point: The Bomb and the Cold War on Netflix — Episode 7, starting around minute 40.

Discreet, efficient, and unglamorous, this was — I would argue — one of America’s quietest triumphs in nuclear security. And Andy Weber, who helped lead the mission, remains one of my personal heroes. The fact that almost no one knows his name, or this story, is a shame.

The Budapest Memorandum

Sadly, the very same year brought a tragic counterpoint.

At the Budapest OSCE summit in 1994, Ukraine agreed to surrender the world’s third-largest nuclear arsenal — 1,800 warheads — in exchange for “assurances,” not “guarantees.” The difference seems slight but the distinction was fatal in military terms. As one American later put it in the wonderful Netflix documentary “Turning Point: The Bomb and the Cold War”: a guarantee means the 82nd Airborne is coming; an assurance means sympathy.

Ukraine likely understood the risk but wanted recognition and a seat at the diplomatic table. But when Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, and again invaded in 2022, the platform proved hollow. Western military aid came, but it was slow, fragmented, and hedged by prohibitions on striking deep inside Russian territory — all in the name of “not provoking” a nuclear power.

The faint echo of appeasement from 1938 was unmistakable. Avoiding escalation made sense on paper, but in practice it rewarded aggression. Nuclear coercion works if promises are hollow.

Zelensky captured the irony (video here): “Either Ukraine will have nuclear weapons, which will serve as protection, or it must belong to some kind of alliance. Apart from NATO, today we do not know any effective alliance.”

This was precisely the outcome Clinton had hoped to avoid. And yet by tying security to fragile language, the U.S. sowed the seeds of today’s disillusionment. In fact, were Clinton to have insisted on guarantees, the Kremlin most likely would have never dared to attack in the first place — water under the bridge now.

Operation Midnight Hammer

On 21 June 2025, in a dramatic and calculated escalation, the United States launched Operation Midnight Hammer—a precision strike on Iran’s most fortified nuclear facilities.

The mission marked the first wartime use of the 30,000-pound GBU-57 Massive Ordnance Penetrator (MOP), dropped from B-2 bombers on the Fordow and Natanz enrichment sites. Backed by over 125 aircraft and a wave of Tomahawk cruise missiles, the objective was not simply to degrade Iran’s nuclear capabilities—but to eliminate them.

Iran does not currently possess a nuclear weapon. But according to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), it had amassed enough enriched uranium—much of it at 60% purity—to construct multiple warheads if pushed to weapons-grade.

Weaponization is more than just stockpiles; it requires infrastructure, secrecy, and intent—not only to build a warhead, but to pair it with a delivery system like a missile or submarine, which Iran currently lacks. In theory, however, a crude device could still be deployed by truck or other ground-based means. Still, with Tehran repeatedly threatening to “wipe Israel off the map,” both the U.S. and Israel viewed inaction as intolerable.

The targets—Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan—represent the heart of Iran’s nuclear program. Natanz and Fordow are Iran’s only known enrichment sites. Natanz had already been struck by Israeli airstrikes on June 13, reportedly disabling key centrifuge halls and support infrastructure—critically, clearing a path for U.S. air operations.

Isfahan, a sprawling complex for uranium conversion and centrifuge production, was also targeted—first by Israel, then by U.S. Tomahawks. But it was Fordow, buried deep beneath a mountain near Qom, that posed the greatest challenge. Constructed to survive aerial assault, it housed thousands of IR-1 and IR-6 centrifuges operating in open defiance of the 2015 nuclear deal. Since the U.S. exited that agreement in 2018, Fordow had become both a symbol of resistance and the front line of Iran’s sprint toward weapons-grade enrichment.

As so often, this so-called “overnight success” was 15 years in the making. General Dan Caine and his team at the Defense Threat Reduction Agency had been studying Fordow since 2009, when classified satellite imagery first revealed the massive subterranean complex. Realizing early on that no existing weapon could reach its depths, they began an extraordinary engineering journey—collaborating with industry, running hundreds of tests, and ultimately developing the GBU-57 Massive Ordnance Penetrator. American excellence at its finest.

But the GBU-57 is not just any bomb—it weighs 30,000 pounds and can only be delivered by the U.S. Air Force’s B-2 Spirit stealth bombers. No aircraft in Israel’s arsenal is capable of carrying or deploying it. That’s why, despite Israel’s extensive preliminary strikes and deep intelligence work, it was the United States alone that could finish the job. This technical reality underpinned a deeper strategic model that unfolded in Operation Midnight Hammer: a new form of allied coordination.

Over the course of a week, the Israel Defense Forces carried out extensive strikes against radar, air defense systems, and nuclear infrastructure, likely with intelligence boots on the ground. Then, with Iranian skies blinded and defenses disoriented, America delivered the high-tech knockout blow—without incurring the political cost or the battlefield risk of putting U.S. soldiers in harm’s way. It was a division of labor that played to each nation’s strengths. And it may serve as a model for future joint operations against rogue actors who threaten regional or global security.

On June 21, fourteen of these 30,000-pound bombs were dropped by B-2 Spirit bombers, flown non-stop by both active-duty and Missouri National Guard pilots out of Whiteman Air Force Base. The strikes hit with such force that pilots reported the explosions turned night into day. Behind the scenes, thousands of scientists, airmen, and technicians had spent over a decade preparing for this moment. In General Caine’s words, this was a uniquely American feat: “We think, we develop, we train, we rehearse, we test, we evaluate—every single day. And when the call comes, we deliver.”

Despite the operation’s scale and technical sophistication, early assessments were cautious. President Trump called the attack a “spectacular success,” but U.S. and Israeli officials acknowledged that Fordow was damaged, not destroyed. Some intelligence suggests Iran may have moved uranium out in advance, though satellite imagery shows mainly defensive measures—sealed tunnel entrances, dump trucks positioned outside.

However, one troubling question remains: where is the 400 kilograms of 60% enriched uranium that the IAEA previously confirmed was stored at Isfahan? Its current location is unknown. While this amount of material represents a serious step toward a bomb, there’s an important caveat: 60% enriched uranium cannot sustain a nuclear chain reaction. At worst, it could be used in a dirty bomb—a psychological weapon causing panic and radiation exposure, but not a nuclear explosion. Moreover, with its economy under heavy sanctions, Iran lacks the resources to quickly or covertly rebuild its enrichment infrastructure.

"One last story about people,” General Dan Caine said at the the Press Conference of Operation Midnight Hammer, the closes spectacle yet to General Schwarzkopf’s nightly episodes in 1992: “When the crews went to work on Friday, they kissed their loved ones goodbye, not knowing when or if they'd be home. Late on Saturday night, their families became aware of what was happening. And on Sunday, when those jets returned from Whiteman (Air Force Base), their families were there, flags flying and tears flowing. I have chills literally talking about this.” And Caine offered a warning to America’s foes as he wrapped up his comments. “Our adversaries around the world should know that there are other DTRA team members out there studying targets for the same amount of time,” he said.

President Trump has been clear that Iran must never acquire nuclear weapons—and that these were limited, targeted strikes. “Iran must now make peace,” he declared. General Caine echoed that clarity in his Pentagon briefing. In our view, this operation was a rare example of how escalation, when grounded in purpose and executed with precision, can create the conditions for de-escalation and global stability.

Our goal here isn't to speculate on what Iran’s Supreme Leader (a title that almost invites irony) might do next. We believe he is consumed with regime survival. The real takeaway is this: Trump’s decision—executed in close coordination with Israel, which had spent the previous week softening Iran’s defenses—was a direct message to any rogue state contemplating the pursuit of nuclear weapons. In that sense, Trump didn’t just destroy two nuclear facilities—he set a precedent.

And in nuclear history, precedents matter, as I have hopefully explained by now extensively. Does this mean the world is out of the woods when it comes to nuclear proliferation? Sadly not. Let me explain…

The Versailles Moment of the post Cold War Nuclear Order?

If the U.S.–Soviet Cold War nuclear race produced anything constructive, it was communication.

However insane the arms race, both sides recognized — especially after the Cuban Missile Crisis — that silence could be fatal. The red hotline, summit diplomacy, verification regimes, and arms control treaties became ritualized acts of survival. Even when the Soviets lied or cheated, they engaged, because they understood the stakes.

China today is different. Beijing is expanding its arsenal at unprecedented speed — the Pentagon projects over 1,000 warheads by 2030 — but remains entirely unwilling to discuss arms control, share doctrine, or even pick up the phone. There is no red phone. There are no agreed protocols. China prefers opacity, ambiguity, and strategic silence.

And that makes miscalculation more likely, not less. Unlike the Cold War, the flashpoints today are not Berlin or Cuba, but Taiwan and the South China Sea — where decisions unfold in minutes, not months.

Fun Fact:

When Fiona Hill was serving in the Trump 1.0 administration, she received a call from Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov — to inform her that Russia was missing a nuclear weapon. But, he added reassuringly, “Don’t worry — it’s probably just an accounting error.”

Source: Fiona Hill on What Putin Tells Us About Trump - The Political Scene; The New Yorker, 11 July 2025

In Russia, the problem is not silence but spectacle. Nuclear threats aren’t buried in footnotes of policy documents — they are made on state TV, with cinematic flair. Dmitry Kiselyov, often described as Putin’s chief propagandist, once proudly declared: “Russia is the only country in the world that is truly capable of turning the USA into radioactive dust.” His Sunday night show has, for years, featured video simulations of nuclear strikes on Western capitals.

Vladimir Solovyov, another television heavyweight, goes further. Panels on his program joke about reducing New York or London to ashes. Margarita Simonyan, head of RT and a frequent guest, once remarked on air: “We’re all going to die someday,” to which Solovyov added, “But we’ll go to heaven; they’ll just croak.” These conversations are carried to millions of Russian households as entertainment, normalizing nuclear annihilation.

This normalization of apocalypse is not strategy — it’s recklessness. But by numbing the public, it lowers thresholds in the Kremlin itself. When nuclear destruction becomes casual entertainment, its real-world use becomes easier to imagine.

Together, China’s silence and Russia’s spectacle dismantle the very communication structures that kept the Cold War cold. The risks are immense, and we are sleepwalking into them.

In many ways, the nuclear era is entering a Versailles moment — where high expectations collide with bitter self-interest. The post-Cold War ideal was simple: the P5 would slowly disarm, others would abstain, and the U.S. would protect its allies under a reliable nuclear umbrella.

That illusion is cracking.

Allies now openly question whether the U.S. would truly trade New York for Taipei, or Vilnius. And rightly so.

Trump’s nuclear contradictions only amplify the anxiety: calling for arms control with Russia and China while simultaneously undermining confidence among allies. That’s precisely how you get what the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) was designed to prevent — a chain reaction of new nuclear states.

In Europe, serious voices now speak the once unthinkable. Germany’s Die Welt recently asked, Brauchen wir die Bombe? — Do we need the bomb? Poland wants U.S. nukes on its soil. In Asia, South Korea and even Japan debate whether it’s time to break nuclear taboos. In the Middle East, Turkey and Saudi Arabia openly vow to match Iran, warhead for warhead.

So far, these conversations haven’t resulted in action. But that doesn’t mean they won’t. And we certainly don’t know everything. (Think Israel.)

Once again, expectations meet reality: the expectation that the U.S. umbrella would last forever. The reality that Moscow and Beijing have rendered nuclear disarmament — the supposed long-term goal of the NPT — not just implausible, but absurd. This disillusionment is now pushing both allies and opportunists toward their own nuclear options.

You may argue — rightly — that acquiring nuclear weapons is difficult. And yes, it is. Designing a working bomb is a multi-year, resource-intensive effort. It requires acquiring fissile material, mastering enrichment, ensuring weapon miniaturization, and marrying the warhead to a reliable delivery system.

But difficult doesn’t mean impossible. North Korea managed it — with a GDP smaller than West Virginia. The Islamic Republic of Iran has come dangerously close, despite years of sabotage and sanctions. Pakistan — a nation riddled with corruption and internal conflict — built and exported its own nuclear program. The precedent exists.

And here’s the uncomfortable truth: a determined nation does not need a perfect ICBM or a nuclear submarine. In a world where deterrence is often psychological, even a crude device matters. A small state — say, one of the Baltics — could, under existential threat, pursue a basic nuclear deterrent or even a dirty bomb. It wouldn’t need to vaporize a city — just to make the cost of occupation unacceptably high.

What other choices would they have in a world where great powers act in pure self-interest?

This is the real Versailles moment — where shattered illusions give rise to dangerous improvisation. The system that once promised stability now invites improvisation, uncertainty, and risk. And history tells us: when rules collapse, the race begins.

From MAD to Multipolar Uncertainty

During the Cold War, nuclear deterrence paradoxically created a form of stability. Washington and Moscow built arsenals so vast that no first strike could be survived. Mutually Assured Destruction—MAD—became the grim equilibrium. It was terrifying, but it was also clear. The certainty of annihilation at the strategic level reduced the probability of nuclear war.

Yet this very stability produced what theorists called the Stability–Instability Paradox: because both sides feared escalation to Armageddon, they tolerated risks further down the ladder.

Proxy wars flourished—in Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan, Africa, and Latin America. Strategic stability at the top bred tactical instability below. Still, the red lines at the highest level held. After the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, Washington and Moscow built hotlines, signed arms control treaties, and honed the art of nuclear crisis management. It was a kind of maturity born from terror.

Today, however, we face a different and, perhaps, far more precarious reality.

The old guardrails have crumbled. Russia under Putin has shredded the arms control frameworks of the Soviet era, suspended New START, and normalized nuclear threats as televised spectacle. Meanwhile, China rejects arms control outright, expanding its nuclear arsenal rapidly—Pentagon projections estimate over 1,000 warheads by 2030—while refusing transparency or even a hotline with Washington. Where Moscow and Washington once engaged in uneasy communication, Beijing prefers silence.

At the same time, technological advances have shortened the fuse. Hypersonic delivery systems, cyberattacks targeting command-and-control infrastructure, and AI-assisted targeting compress decision cycles from minutes to seconds. In the Cold War, Kennedy had days to deliberate during the Cuban Missile Crisis; today, a flashpoint in Taiwan or the Baltics could escalate into nuclear catastrophe before leaders even pick up the phone.

The paradox has shifted. Where once the world was dangerous but structured—nuclear war unlikely but proxy conflicts abundant—today fewer proxy wars rage, yet the risk of direct nuclear miscalculation is greater than ever. The old assumption that deterrence alone guarantees peace has proven fragile. And that disillusionment is spreading—among allies, adversaries, and the global public alike.

Is Nuclear War Inevitable?

The likelihood of nuclear war is a matter of both independent and interdependent probabilities. Paradoxically, reducing the probability of an all-out catastrophe requires that we learn to accept a certain degree of risk and uncertainty.

This question is discussed here.

The Illusion Cycle: Democracies, Defense, and the Price of Complacency

If Woodrow Wilson set expectations too high in 1919 by promising freedom and self-determination far beyond Europe, then the post-1945 security order repeated the pattern in reverse. NATO and America’s nuclear umbrella created expectations of perpetual peace—expectations that soared even higher after 1991 with the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In both cases, the coin was the same: too much was promised, and too little could ever be delivered. In 1919, the disappointment fueled revolutions, nationalist movements, and the rise of communism. After 1991, it fostered illusions of a peace dividend, underinvestment in defense, and the brittle sense that history itself had ended. Both illusions collapsed when reality returned.

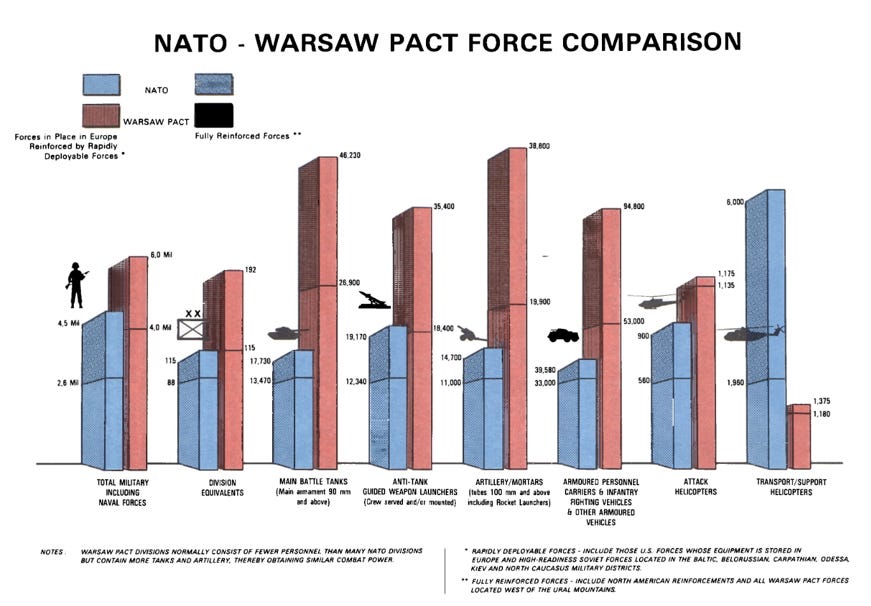

Democracies in particular swing like a pendulum. During the Cold War, the West and the Warsaw Pact stood armed to the teeth, with vast standing armies and massive nuclear arsenals. By the mid-1980s, the Warsaw Pact fielded more than six million troops; NATO responded with roughly 4.5 million. Add to this the neutral states—Sweden with 180,000 soldiers, Finland with 30,000 active and hundreds of thousands in reserves, Norway with nearly 40,000, and Switzerland with close to 625,000 in uniform (you read that correctly) and alternating service on a population of 6.5 million, nota bene (Armee 61)—and Europe was anything but a free rider.

In this historical context, accusing Europe of free-riding is neither helpful nor accurate. At best, it reveals ignorance; at worst, bad faith. Europe was armed and mobilized, standing guard across the Iron Curtain. If anything, European armies were the first line of defense for the United States—a cynical observer might say they were America’s “gun fodder.”

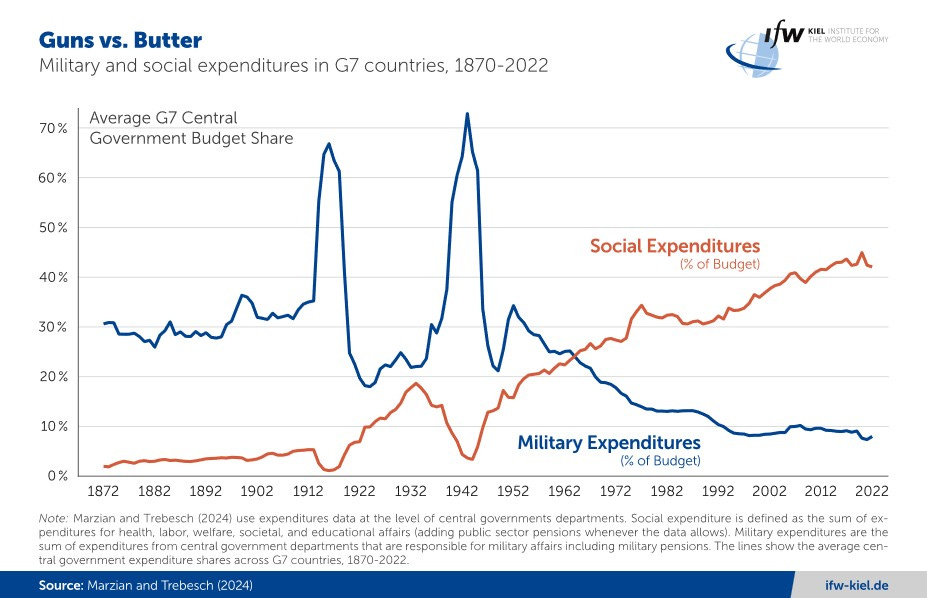

Then came 1991 and the Soviet Union’s dissolution. Instead of recalibrating prudently, Western democracies—and Europe especially—indulged in what I call the “age of butter”: the belief in a never-ending peace dividend that never truly existed. Defense budgets were slashed, social spending ballooned, even as early warning signs mounted. By 2014, when Russia seized Crimea, the illusion of perpetual peace was bankrupt. Yet politicians ignored the warning, unwilling to deliver inconvenient truths or shift the Overton window. This remains a critical political failure. But as the saying goes, the people get the politicians they deserve—so we are all guilty as charged.

Today, the “age of butter” persists across G7 nations—Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK, and the US—as military spending shrinks to historic lows while social spending on health, labor, welfare, education, and social affairs steadily grows. This pattern holds whether measured as a share of government budgets or as a percentage of GDP — and it’s a disgrace.

Meanwhile, the authoritarian world moves in the opposite direction. Xi Jinping’s China has embraced a nationalist right, centralizing power and tightening ideology. Putin’s Russia is a toxic blend of authoritarianism, plunder, and institutional decay, producing a predatory and unstable neighbor. From Beijing to Moscow, the illusion of “responsible stakeholders” has dissolved into a looming security threat.

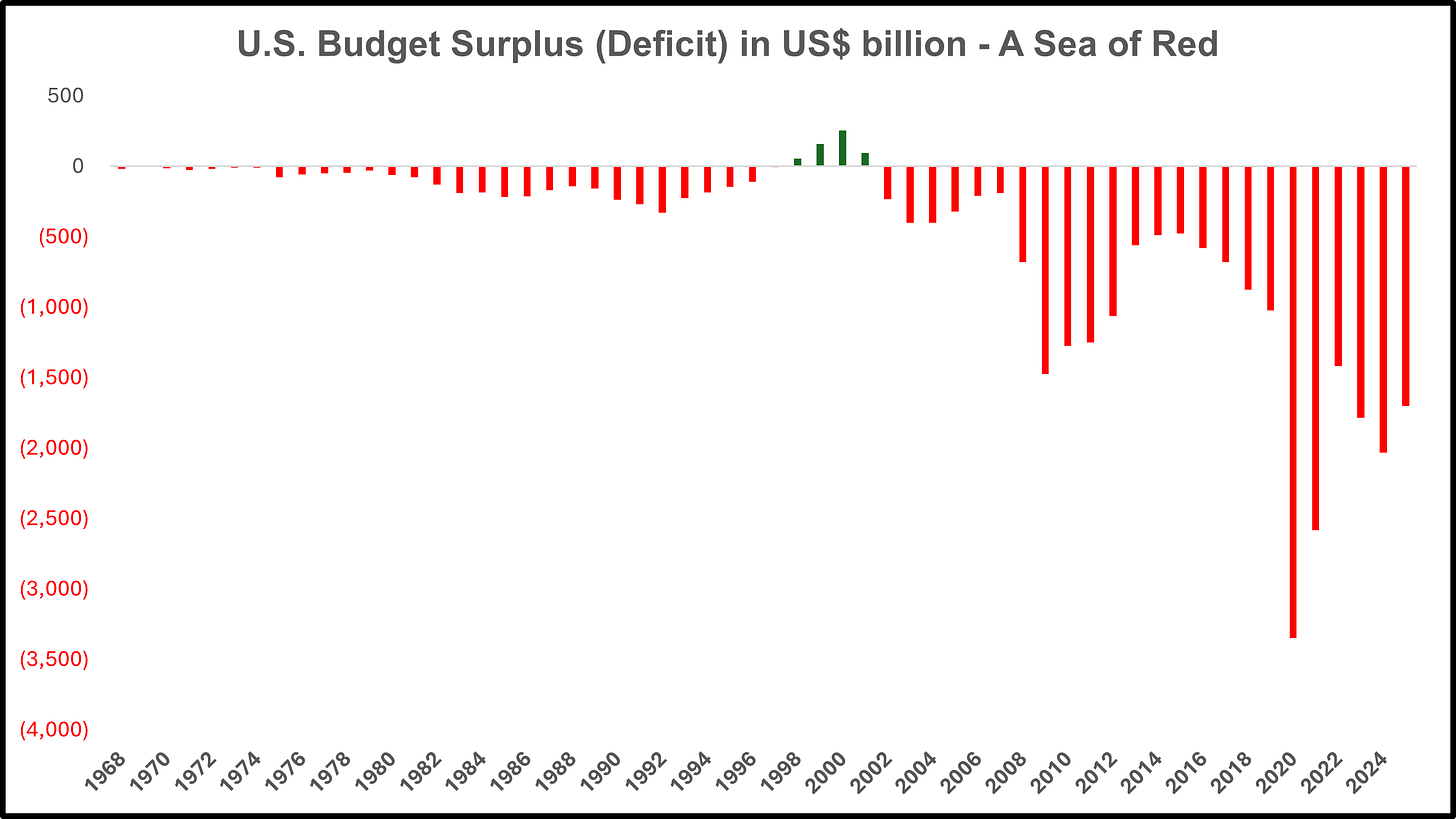

America’s role is complicated. The Bush Jr. administration’s ill-fated wars in Iraq and Afghanistan bred disillusionment and “foreign policy fatigue” among American voters. Both Democrats and Republicans, rather than confronting the tough realities of sustained global leadership, opted for fiscal sugar highs—running deficits of five to seven percent of GDP annually to buy time and votes. The only recent exception was Bill Clinton, who briefly balanced the budgets around 2000.

Under Trump 2.0, the deficit is forecast to reach $1.7 trillion in 2025 and $2.6 trillion by 2035, as fiscal challenges remain unaddressed—especially entitlement programs like Medicare and Social Security. Meanwhile, the costly wars in Iraq and Afghanistan wasted trillions.

The pitfall of high expectations is universal.

Too much was expected of America’s nuclear umbrella, too much of Russia’s willingness to be a stable neighbor, too much of China’s commitment to global rules, and too much of fiscal sleight of hand to preserve domestic comfort without sacrifice. When these expectations are betrayed, the pendulum swings hard—from hope to bitterness, from trust to disillusionment, from peace to renewed conflict.

The Imperative of Shared Responsibility

The lesson of 1919 stands stark and unforgiving: overloaded peace breeds disillusionment. From the rise of communism to the tangled legacy of Sykes–Picot, from the wars in Indochina and the Middle East to the nuclear bargains of the Cold War—right up to today’s collapse of communication with China and Russia, the nightly nuclear theater on Moscow’s state TV, and the tragedy unfolding in Ukraine—these are variations on the same tragic error. High expectations, fragile bargains, and the inevitable disillusionment when harsh reality intrudes.

Unwelcome nuclear proliferation now looms as the latest consequence of these unbalanced policies. America’s efforts to stem it have often been prudent, but the path has been uneven and fraught with contradictions. As U.S. power faces new limits amid financial restraint and political fatigue, the risk of a nuclear cascade grows ever more real.

Yet Western deterrence cannot—and must not—rest on fragile expectations or temporary assurances. Countries need security architectures grounded in trust, mutual responsibility, and credible deterrence that transcend short political cycles. Democracies, in particular, must craft durable security models designed to outlast fleeting electoral mandates. Charles de Gaulle grasped this early, forging France’s independent nuclear deterrent as a sovereign safeguard beyond partisan politics.

High hopes without deep, systemic foundations are a naïve recipe for disappointment. As Einstein famously warned: “I know not with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones.”

If peace fails us now, the conflicts of tomorrow may be unimaginable—and unthinkable.

Warm regards,

Alexander Stahel

What an incredibly informative and well crafted post