False Virtue Signalling & Humiliations Won't Bring Peace

Lesson 5

Lesson 5: Whoever Humiliates the Defeated Turns Peace into a Mere Armistice

There can be no durable peace without communication—and whoever humiliates the defeated reduces peace to a fragile armistice.

The Napoleonic Wars (also known as the Coalition Wars; see Appendix below for a brief refresher) offer a vivid early-modern lesson in how peace can be theatrically staged and symbolically charged, yet fail to take root when one side is humiliated and sidelined.

In June 1807, a river pavilion was erected—on two specially constructed rafts in the middle of the Memel River near Tilsit, in what is now modern-day Sovetsk, Russia. Under intense time pressure, French military engineers decorated the floating structure with luxurious wallpaper and fine furnishings to host a meeting between Napoleon Bonaparte and Tsar Alexander I.

The goal was to project mutual respect and sovereign equality, with the meeting’s location—exactly at the midpoint of a border river—chosen to symbolize neutrality and balance. This stagecraft is vividly captured in the painting above, where flags, wreaths, canopies, and the armies arrayed on either bank reinforce the illusion of equal footing.

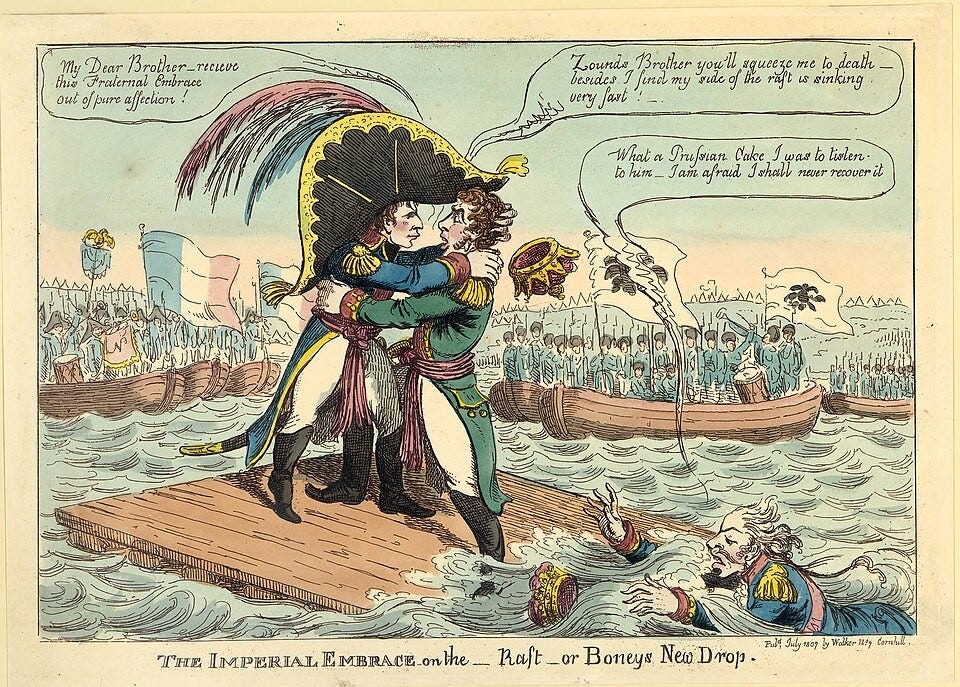

But the illusion was deliberate. A contemporary British caricature (see top picture) conveys the underlying power dynamic far more accurately: Napoleon and Alexander embrace in theatrical warmth, while the Prussian king—drenched and desperate—struggles in the water, his crown adrift, powerless.

The Peace of Tilsit ended hostilities between France and Russia—but was not a foundation for lasting peace. Napoleon viewed it as a temporary convenience, a step toward consolidating power rather than reconciling differences. Five years later, he invaded Russia with over 600,000 troops—an ambition that would prove catastrophic.

Prussia, treated as an afterthought during the negotiations, suffered half its territory stripped away and was relegated to the role of a buffer state. Queen Louise’s emotional and ultimately futile plea for leniency turned her into a tragic, mythic symbol of national suffering—one that shaped German nationalist memory and helped fuel the Franco-Prussian War six decades later.