The Paradox of Winning and Losing War and Peace

Lesson 7

Lesson 7: The Paradox of Winning and Losing War and Peace

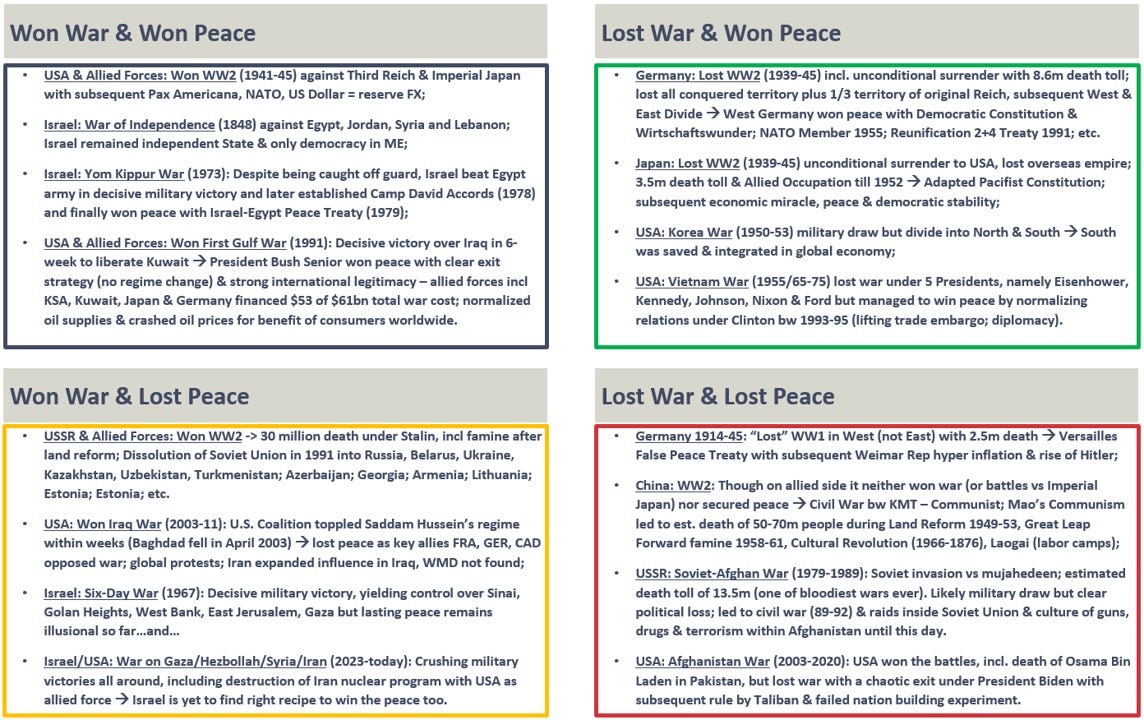

History reveals a paradox: you can win the war but lose the peace, lose the war but win the peace—or lose and win both at once. I illustrate this paradox in my above matrix for a few selected examples on the basis of 259 distinct state-based armed conflicts (link) since 1946 and will discuss three examples in detail below.

Example 1: Operation Desert Storm — When Strategy, Stability, and Serendipity Aligned

In the summer of 1990, military planners at Fort Irwin, California, were running Exercise Internal Look ’90, a war game simulating an Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. When Saddam Hussein actually launched his invasion—at 2 a.m. on August 2—the line between rehearsal and reality vanished overnight.

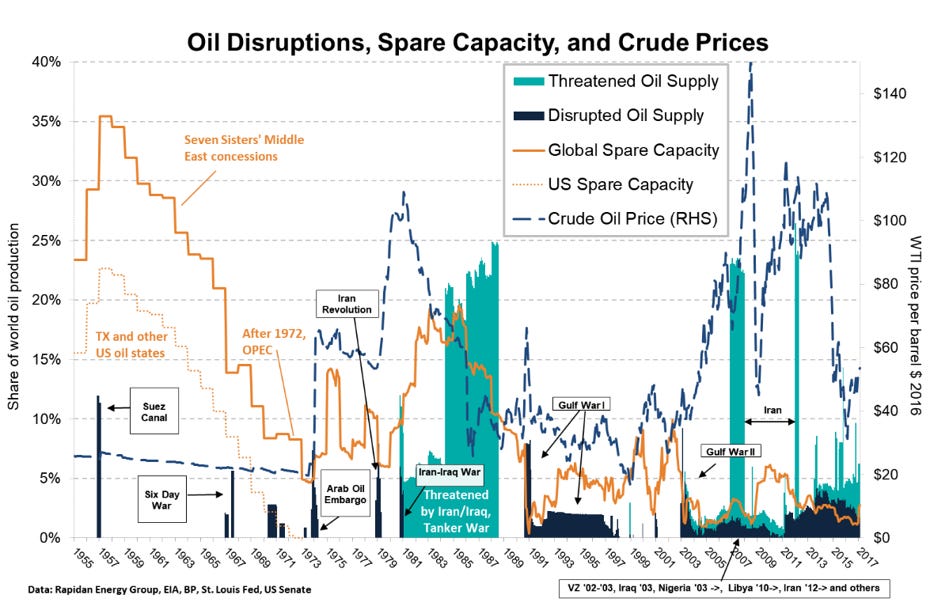

This was no mere border spat. Saddam Hussein’s move was an oil war, born of desperation and ambition. After an eight-year war with Iran, Iraq’s finances were devastated—its coffers empty, infrastructure battered, and foreign debt climbing to around $80 billion. Saddam demanded debt forgiveness from Gulf allies; they refused. He accused Kuwait of “slant drilling” into Iraq’s Rumaila oil field and used that as justification for aggression.

In truth, it was blackmail: seize Kuwait’s reserves, threaten oil stability, and control nearly 40% of OPEC’s production. Domestically, Saddam ruled through terror, corruption, and a cult of personality—no internal governance or restraint.

Markets panicked. West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude jumped from $17 in June to nearly $40 by late September, shimmering with fear. Kuwait’s fall—an export titan and key Western supplier—was catastrophic.

Fun fact:

Did you know that Saddam Hussein, in full defiance of international norms, ordered retreating Iraqi forces in February 1991 to set Kuwait’s oil fields literally on fire. Over 600 wells were torched in a calculated act of scorched-earth sabotage, unleashing one of the worst environmental disasters in modern history. Thick black smoke blanketed the skies for months, damaging ecosystems, choking nearby cities, and stoking fears of prolonged global supply disruption.

Fund fact 2:

Did you know that a brilliant company freshly born out of the ashes of communist Hungary—MB Drilling, a division of Oman’s MB Group—sent a Soviet-era tank retrofitted with twin MiG-21 jet engines, dubbed “Big Wind,” into the Kuwaiti oil fields? In just 43 days, that clever contraption quelled nine raging oil well fires using nothing more than jet-powered blast cooling and water—the kind of industrial theater that still boggles the imagination. Here a link.

Saudi Arabia’s role as the swing producer crystallized. With vast reserves but only ~2 mb/d of spare capacity, it was the world’s only meaningful supply buffer. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union—already ailing—saw oil production fall 6% in 1990, foreshadowing a staggering 56% decline over the decade. China’s demand was beginning to rise too. The result: oil’s global spare capacity near zero (remember my recent oil thread here?) and peak global energy anxiety.

But beyond energy and arms lay strategic fortune—what one might call strategic luck. Mikhail Gorbachev faced a planned-economy ruin, military overstretch provoked by Reagan’s Strategic Defense bluff, and internal reform creating more unrest than renewal. Glasnost (openness) unleashed criticism; Perestroika (economic restructuring) disrupted the economy. Eastern Europe collapsed. The Two‑Plus‑Four Treaty (September 12, 1990) cemented German reunification and further occupied Moscow. Unbeknownst to many, Bush’s greatest adversary was disintegrating from within.

At home, however, Bush faced the haunting shadow of Vietnam. Many Americans bristled at another Middle East entanglement. But Bush reframed the crisis—not as an oil war but as a just war for global stability, sovereignty, and international law. Saddam’s aggression, he argued, was not America’s problem—but the world’s. The narrative stuck.

Bush took the fight to Capitol Hill—and won authorization by the skin of his teeth: 250–183 in the House, 52–47 in the Senate. It was a narrow, politically delicate mandate—but it was real. At the same time, he secured crucial international legitimacy through UN Security Council Resolution 678, passed on November 29, 1990, which gave Iraq a firm deadline to withdraw from Kuwait and authorized member states to use “all necessary means” if it failed to comply. The resolution passed with a strong majority—12 in favor, only 2 against (Cuba and Yemen), and 1 abstention (China)—further strengthening Bush’s hand at home and abroad. In other words, Bush Sr. secured legitimacy like a pro. Did you know or remember all that?

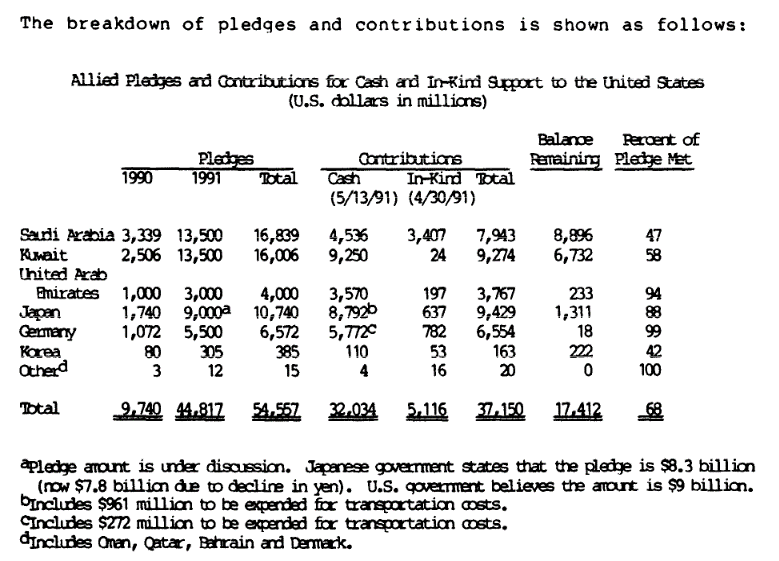

Then came the money. Bush did something often missed in today’s “America First” lens and age of X-bullshit narratives: he made key allies pay—and not just token amounts. The coalition’s war chest wasn’t funded solely by U.S. taxpayers. In fact, only a minority portion was. Nations like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Japan, and Germany stepped up, not out of charity, but because they had skin in the game. All had a strategic and economic interest in resolving the crisis quickly and preserving oil flows. Both Japan and Germany, in fact, imported a greater percentage of their oil than the U.S. did at the time. One administration report estimated that allies covered roughly 80% of U.S. costs for the Desert Shield operations. Now that IS a great deal.

This wasn’t just fiscal pragmatism—it was political savvy. Unlike the later flood of narratives accusing allies of freeloading, Bush’s administration actually demonstrated what coalition burden-sharing looks like in practice. Truman—of course—did something similar after WWII with the Marshall Plan. Bush didn’t invent the playbook, but he dusted it off, used it well, and reminded the world how diplomacy and leadership can align. Post World War 2 America was always "America First"—but perhaps with a bit more class and foresight?

Inside the Situation Room, Bush wrestled with military options. General Norman Schwarzkopf (one of my personal leadership heros as I happened to have been in Swiss Officer School during his Operations and watched him carefully) used a sand table and toy tanks to demonstrate the now-iconic “left hook” maneuver—a sweeping ground assault through desert that would outflank Iraqi defenses. Its clarity reassured both Bush and Cheney. This wasn’t quagmire—it was executable strategy.

Operation Desert Storm kicked off on January 17, 1991. In 42 days, the U.S.-led coalition dismantled Saddam’s forces. The ground war lasted just four days and culminated in Kuwait’s liberation. General Schwarzkopf’s nightly briefings—calm, clear, authoritative—became a new wartime cadence, projecting command credibility to the world. And boy he had it. Schwarzkopf was what I like to call a natural leader. People would follow him to hell and back.

Without any doubt, General Norman Schwarzkopf’s leadership—alongside meticulously coordinated planning cells—was instrumental in engineering the swift and overwhelming military campaign that, in conjunction with the diplomatic finesse of President George H. W. Bush and his team, successfully expelled Saddam Hussein’s forces from Kuwait.

And while some later criticized the decision not to march all the way to Baghdad — let that sink in, especially in light of today’s geopolitical hindsight — Schwarzkopf delivered a prophetic warning that those leading the 2003 invasion would have done well to heed:

“Had we taken all of Iraq, we would have been like a dinosaur in the tar pit — we would still be there, and we, not the United Nations, would be bearing the costs of that occupation.”

Senior Bush not only won the war, he won the peace. He restored American prestige, shattered the “Vietnam Syndrome,” renewed public confidence, and re-legalized force as a tool conditioned by coalition and moral purpose. Crucially, oil markets stabilized: prices slid back to ~$20 per barrel by mid-1991. Saudi Arabia ramped production from 5.4 to ~8.5 mb/d, and Kuwait — though devastated — ramped back up to ~1.6 mb/d by late 1992, approaching full capacity soon after.

Desert Storm became a post-WWII rarity: a war whose ending reinforced peace. Military victory, strategic restraint, market stabilization, alliance cohesion, morale regained, and energy security secured—all achieved. Bush Sr., through diplomacy, burden-sharing, precision, and a dose of strategic fortune, delivered what so few leaders ever do: a war that healed more than it harmed.

With the benefit of 55 years of hindsight, I might add: December 1991 may have marked the peak of Western civilization—for now.

Yet irony endured. The architect of one of modern America’s most successful military-diplomatic campaigns lost the 1992 election to Arkansas governor Bill Clinton. For voters, the home front mattered most. As the campaign mantra had it: “It’s the economy, stupid.” My god, democracies are indeed a total utter mess.