China’s Paradox Under Xi - Episode 5 of 7

A Sea /xi:/of Macro Imbalances - a Story Told Through the Lens of its Bust Property Bubble.

Let us continue our journey on China.

In this episode, we will discuss whether China may abandon the current investment-led growth model that created significant malinvestment and record indebtedness and replace it with more consumption (we named it path 2, in episode 4 of 7). You will soon find out that the answer has nothing to do with economic optionalities and everything to do with political preferences or - rather - Xi Jinping himself.

Before we continue, let us briefly recap the property picture as explained in the past four episodes (1) here, (2) here, (3) here and (4) here:

China’s real estate sector represents 25% of the Chinese economy, 70% of Chinese household wealth and 36% of local government revenues. But today, China’s real estate sector faces huge challenges: the equivalent of one and a half Japan standing vacant, one Netherlands available for sale and nearly one United States remains to be completed. Worst, local government revenues from land concession sales are in free fall and have to be replaced with more (future bad) debt.

In order to deflate this bubble, China’s households and private sector economy face a painful and prolonged de-leveraging process in which companies will stop borrowing despite record low interest rates. Instead of maximizing profits, they will minimize risk by paying down debt - a so called “balance sheet recession”. This is happening right now; China is in a balance sheet recession.

However, the investment-led growth model of the CCP that caused the property bubble and widespread industrial overcapacities remains in place. For the past two decades, China’s capital formation has been hovering around 45%. No other G20 economy came even close to such a high number. The CCP is, and remains, in the middle of an unprecedented macroeconomic experiment in human history that has gone largely unnoticed.

The model worked wonders while animal spirits were in full swing due to higher property prices each year. But it also led to significant malinvestment, diminishing returns on investment and a mountain of debt that will prove hard to service. In 2023, China’s total system debt stood at 318% debt-to-GDP, a level comparable to advanced economies but held within the system fragility of an emerging market economy with Chinese characteristics under a “Marxist” leader. Quite a toxic cocktail.

There are only 5 paths China’s economy can follow going forward: (1) it can stay the course and take on more debt. We have explained why that must lead to a form of Great Depression as seen in the U.S. in the 1930s. (2) China can replace malinvestment with consumption. You will learn later in this episode why Xi is not interested in this option. (3) China can replace malinvestment with quality investments or (4) it can replace malinvestment with more exports. The latter two paths are unprecedented in economic history but they are what Xi is pursuing. Finally, China can (5) replace malinvestment with do nothing. The post Soviet Union great depression would be the obvious outcome.

Let us now assess path 2.

Path 2: Can China Replace Malinvestment with Consumption?

Answer: Maybe a little bit and over a long time frame, but President Xi does not want to focus on this path. Instead, he wants to implement his socialist utopia. Let us explain…

From 2020 to August 2024 Chinese households saved CNY 65.4 trillion of bank deposits. That is 50% of their overall accumulated savings of CNY 131.5 trillion since January 2005 and despite April’s record drawdown of CNY 1.85 trillion.

If the Chairman for Life really aims to stimulate private household consumption to shift away from his investment-led growth (irony intended), he is on the wrong track. But does he want do that? The answer is no.

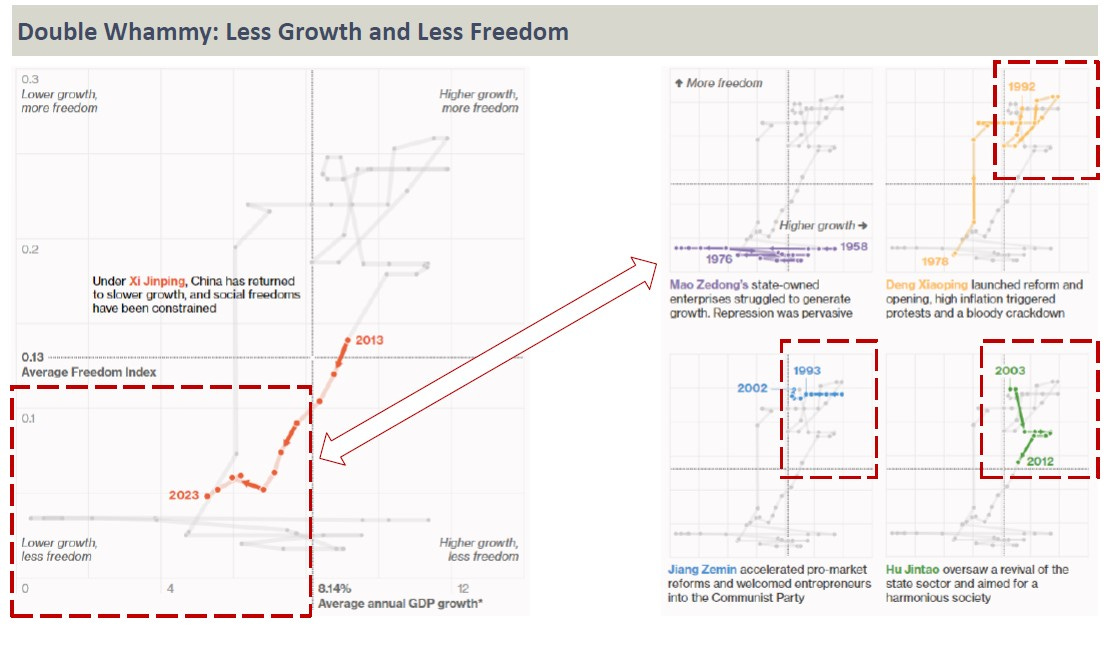

China’s rising entrepreneurs were welcomed into the Communist Party for at least two decades. Under Jiang Zemin’s presidency, that was part of the cautious shift towards a more open society that accompanied rising prosperity in those years.

Under his successor Hu Jintao, there was greater emphasis on social stability — or “harmony” as Hu put it. Civil rights lawyers, labor organizers and land-rights activists could make their voice heard.

All of that is now in reverse. Under Xi Jinping, China has moved full circle: from low growth and low freedom in the pre-reform era back towards something similar today. Take time to study this chart in detail.

It is a paradox that Xi Jinping remains an enigma to most Western commentators, given that for the past 12 years he has been the leader of the world’s largest military, second-largest nation by population size and second-largest economy. Yes, little is known about his personal habits and interests. But if we don’t know much about Xi the man, the same cannot be said about what Xi thinks.

In an interview, Professor Stephen Kotkin, the historian and author of a projected trilogy on the life of Joseph Stalin, explained that Xi Jinping, as a student of the Soviet collapse, spent a great deal of his time and resources figuring out why that happened in the Soviet Union and how it could be prevented in China.

According to Stephen, Xi firmly believes that the failure of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union to fight back against a “traitor” like Mikhail Gorbachev was responsible for the collapse of the Soviet Union. In fact, not just Xi believes that. There is the Central Party school that trains higher cadres. Its number one subject lesson? Avoid the Gorbachev-mistake under all circumstances.

The important point here is that communism is an all or nothing proposition. You can’t be half communist. Either you have a monopoly on power or you don’t. Any attempt to reform communism politically and thereby allow quasi market rights and the accumulation of wealth is an inherent risk to the party’s long-term monopoly on power. As Stephen put it: you don’t politically liberalize a communist system unless you want to commit political suicide. Dubcek tried in 1968 in Prague and Brezhnev sent his tanks to put a stop to it. Gorbachev tried and ruined Soviet Russia, losing it to the communist cause. Deng Xiaoping quashed student protests with his tanks in 1992, avoiding Gorbachev’s fate for the CCP.

Fact is, China’s Leninist structure, that being the Communist Party’s monopoly on power, never went away. However, there was this wishful thinking (in the West) that the Marxist-Leninist ideology was fading even though the Leninist structure had survived. There was this make-believe that Xi Jinping is somehow worried about shaving a point or two off China’s GDP in order to secure the parties monopoly on power and that less growth would hurt living standards and thus cause the regime to lose its “bargain” with the people. But of course, these are what they are: illusions, alternative, parallel realities, Western perception versus the Chinese reality. For the latter, the iron grip of the CCP never went away, not one second.

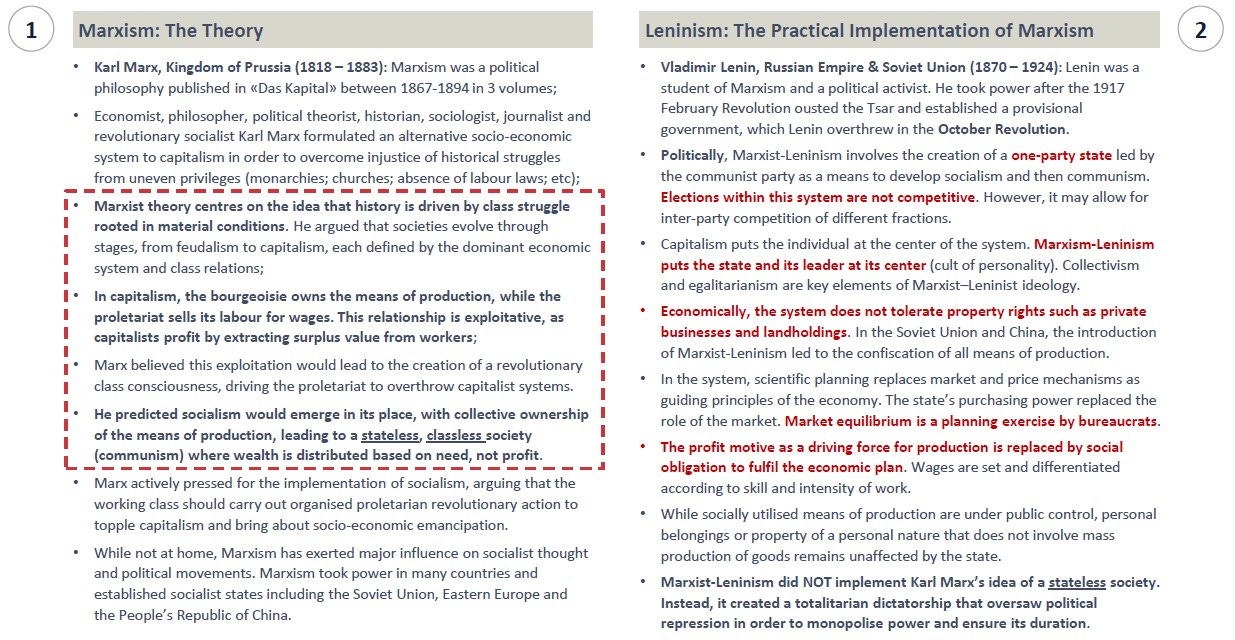

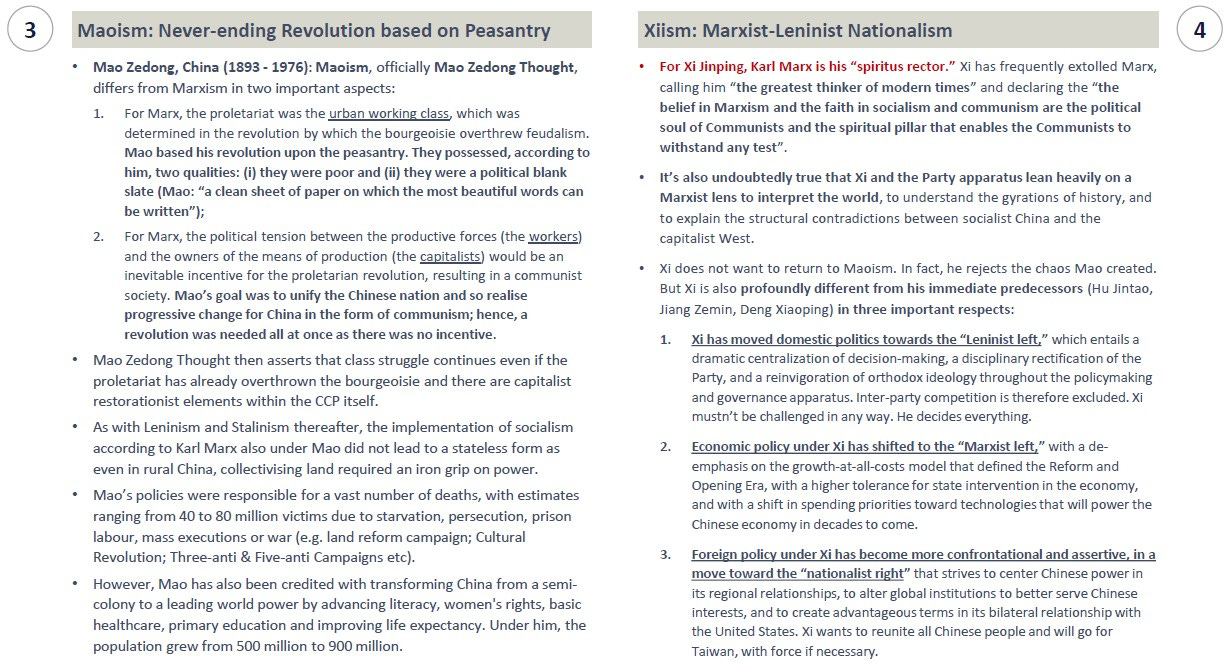

But before we dig deeper, we need to recapitulate the ideological framework, namely Marxism and its various applications and implementations such as Leninism and Maoism.

In his book «On Xi Jinping», Kevin Rudd, former prime minister of Australia who speaks Mandarin and who negotiated with Xi Jinping personally, argues that Xi’s Marxist ideological convictions are genuine and foundational, driving his efforts to assert Party control, reshape the international order, and secure China’s future as a socialist superpower (the Chinese Dream).

To achieve that, the thrust of Deng Xiaoping’s reforms and the trend towards intraparty democracy have been reversed.

Xi moved politics towards the Leninist left (less freedom), economics to the Marxist left (less growth and less private enterprise) and foreign policy to the nationalist right (more confrontational).

Xi therefore pursues governance reforms that strengthen his control over the Party and state apparatus, as well as the Party’s leadership over everyone and everything in China, so as to significantly enhance the reach of the Party - and by extension the reach of Xi himself.

Economically, his priority is on developing a “socialist market economy” – party-speak for a Marxist-style state-led economy in which Xi (not Beijing) directs all resources - to give China the muscle to compete with the West.

In practical terms, it means applying active state steerage, under the direction of Xi Jinping so that the economy can serve his geopolitical agenda to overtake the West, even if it reduces the autonomy and profit of businesses and individuals.

A socialist market economy therefore requires strengthened government control of the economy, thus privileging State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) at the expense of domestic private companies. Xi does not see this as attacking the private sector but merely clarifying the ground rules so that the private sector can thrive in a way that contributes to the economic goals he has set for China.

Thus far, there is no systematic evidence showing that party units have assumed a stronger leadership role at the grassroots level than before. But at least on paper, the latest official figures are trending in the direction Xi favors. There was a party branch in 95.2% of SOEs, 73.1% of private companies and 61.7% of social organizations in 2017, compared with 90.8%, 58.4% and 41.9% in 2013. Remember the Politruk in The Hunt for Red October? That’s these guys.

Xi wants to control and direct the economy to accomplish his vision of making China a socialist superpower. For that, he wants to develop an “independent innovation ability.” This is because, he explained, “currently, a new round of technological revolution and industrial transformation is reshaping the global innovation landscape and economic structure.” Strengthening innovation should therefore be the priority of an aspiring world superpower.

The problem here? Albert Einstein did not formulate his theory of relativity under the order of a government bureaucrat. Nor did Henry Ford revolutionize the auto industry that way. Tesla’s inventions were commercialized by Edison, not by legal requirement. Instead, creative breakthroughs and applied science more likely require freedom from rigid control. If history is any guide, innovation and a resilient economy require the opposite of where Xi is taking the China for the past 12 years.