China's Paradox under Xi - Episode 4 of 7

A Sea /xi:/of Macro Imbalances - a Story Told Through the Lens of its Bust Property Bubble.

Let us continue our journey on China, shall we?

In this episode, we will discuss the Chinese investment-led growth model that the CCP pursued for the past two decades. It turns out this was a unique experiment in economic history. No other G20 country has come close to China’s sustained capital formation when put in the context of other G20 economies. We will discuss if China can continue on this path which created significant malinvestment and record indebtedness. We will also give an outlook for the 4 remaining paths forward China’s economy can follow.

Before we continue, let us briefly recap the property picture as explained in the past three episodes (1) here, (2) here and (3) here:

China’s real estate sector is absolutely massive and analyzing it offers the best insight into the Chinese economic growth model. It represents 25% of the Chinese economy, 70% of Chinese household wealth and 36% of local government revenues.

But today, China’s real estate sector faces huge challenges: the equivalent of one and a half Japan standing vacant, one Netherlands available for sale and nearly one United States remains to be completed. Worst, local government revenues from land concession sales are in free fall.

Not surprisingly, cash-strapped local governments commit fraud at scale to balance their budgets. They artificially boost revenues by selling land concessions to Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs) without any underlying project in existence. In the month of December 2023 alone, such transaction volume reached CNY 1.6 trillion!

In order to deflate this bubble, China’s households and private sector economy face a painful and prolonged de-leveraging process in which companies will stop borrowing despite record low interest rates. Instead of maximizing profits, they will minimize risk by paying down debt - a so called “balance sheet recession”. This is happening right now; China is in a balance sheet recession.

On various occasions, we read that China can avoid a Japan-style, prolonged recession. We disagree and argue that Japan’s economy was in significantly better shape to deal with its balance sheet recession in the 1990s than China’s is today.

The entire Chinese economy has grown analogous to Real Estate: cheap loans doing the bidding of the CCP’s 5-year economic plans, funded industrial capacity build and job creation, generating ever decreasing returns, however, in-line with growing overcapacity relative to domestic and even global demand. This so called investment-led growth model suited the CCP’s ideology, stressing employment growth and state control over individual consumption.

But does it have a future? We don’t think so.

Investment-Led Growth Model

Starting in the early 1990s, China’s economic growth engine has been fueled by capital investments. Its central planning bureau-defined GDP targets within a 5-year plan, picked sector winners, and drove growth from significant debt-driven capital formations (green line in the graph below) to build real estate (often ghost cities), infrastructure or industrial production capacities.

China’s capital formation has been hovering around 45% for more than a decade. As industrial capacities surpassed domestic demand, excesses had to be exported. Of course, this also led to significant malinvestment, as it always does when the state allocates capital (think Belt & Road Initiative). All this came at the expense of household demand (blue line in graph below), as social benefits or higher wages didn’t progress.

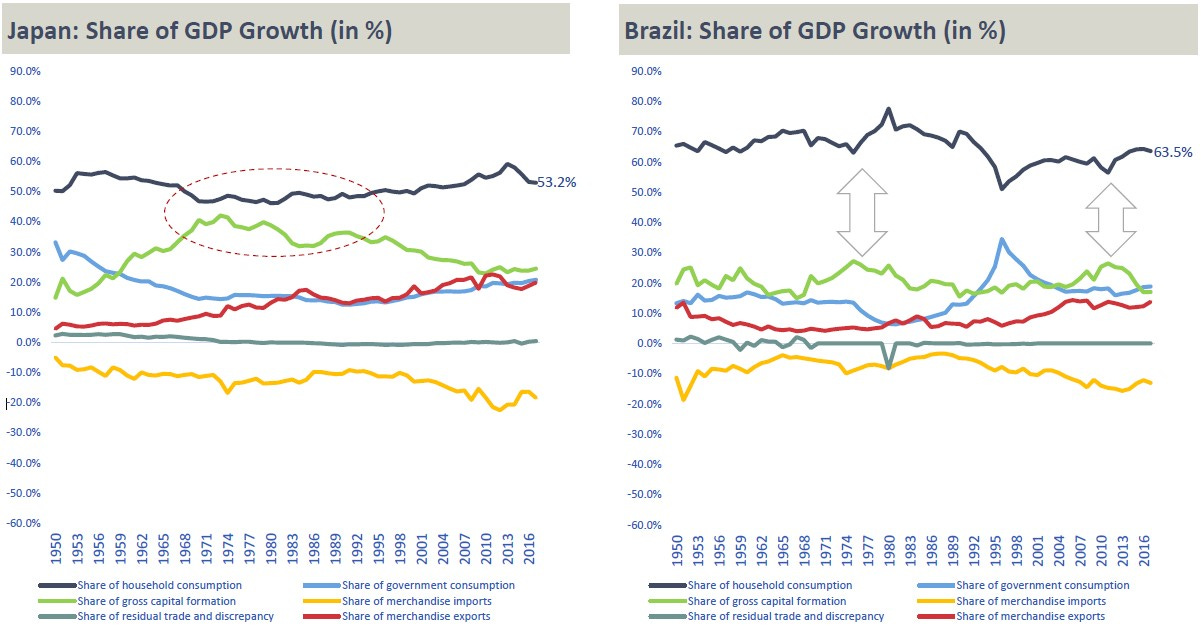

Has any nation tried this before, ever? Not to our knowledge. We looked at all G20 economies and their respective growth model for the past 70 years. No other nation has attempted anything close to what the CCP has been doing for the past two decades.

South Korea came closest (very briefly) when its capital formation crossed household consumption in the late 1990s. India, on the other hand, seems to have learned from China’s challenges and allows consumption to be the pacemaker of growth. Although it also invested more into infrastructure lately, it has done so without throttling consumption.

Obviously, Japan’s economic model comes to mind, too, due to its asset bubble in the early 1990s. Interestingly, during that time its capital formation remained relatively subdued at around 35% and nowhere near China’s 45% while it kept consumption above 50% due to little unemployment, a solid social system and a well-diversified economy. Brazil, another large emerging economy, did not pursue the Chinese model either. No G20 country has!

Do global executives or capital allocators fully understand the risky experiment the CCP is running and that is has run its course? We have our doubts.

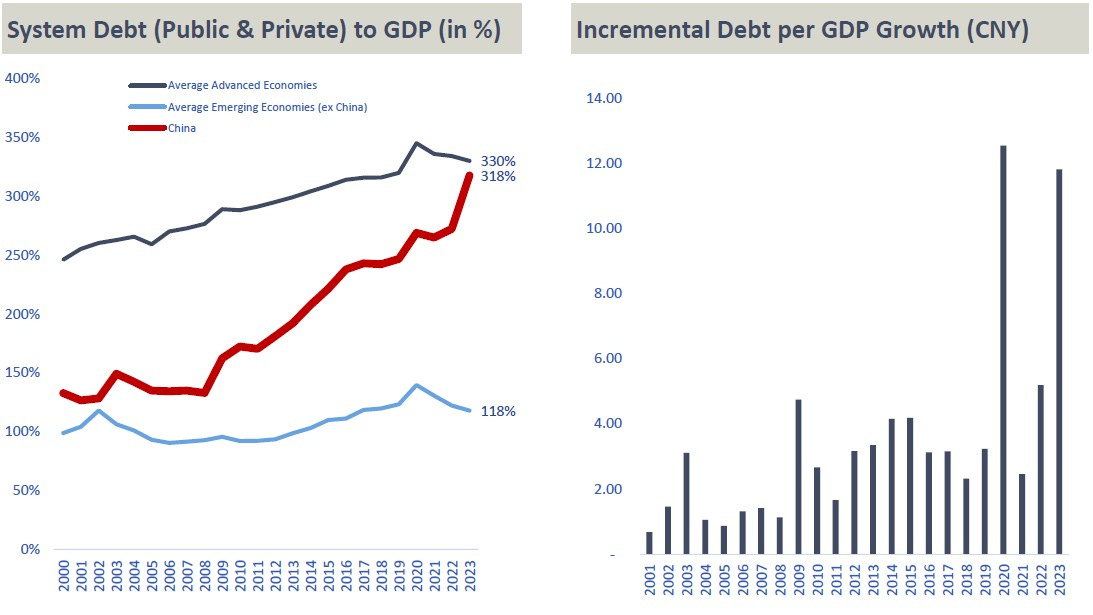

The CCP’s current emphasis on “developing new quality productive forces at a faster pace” and focus on “future industries” is nothing if not an admission that its investment-led growth model has failed. China requires more and more debt to generate an incremental Yuan of GDP.

In 2020 and in 2023, it may have reached an extreme of 12 Yuan of debt for 1 Yuan of GDP growth. China’s command economy is misallocating capital at scale and, in the process, has reached unsustainable debt levels, comparable to developed economies with 4-8x higher GDP per capita. China’s model cannot reduce debt. No wonder the rhetoric shifted to “inward-focused growth”.

There is a growing consensus in Beijing that China’s excessive reliance on surging debt in recent years has made the country’s growth model unsustainable. So what are the alternatives?

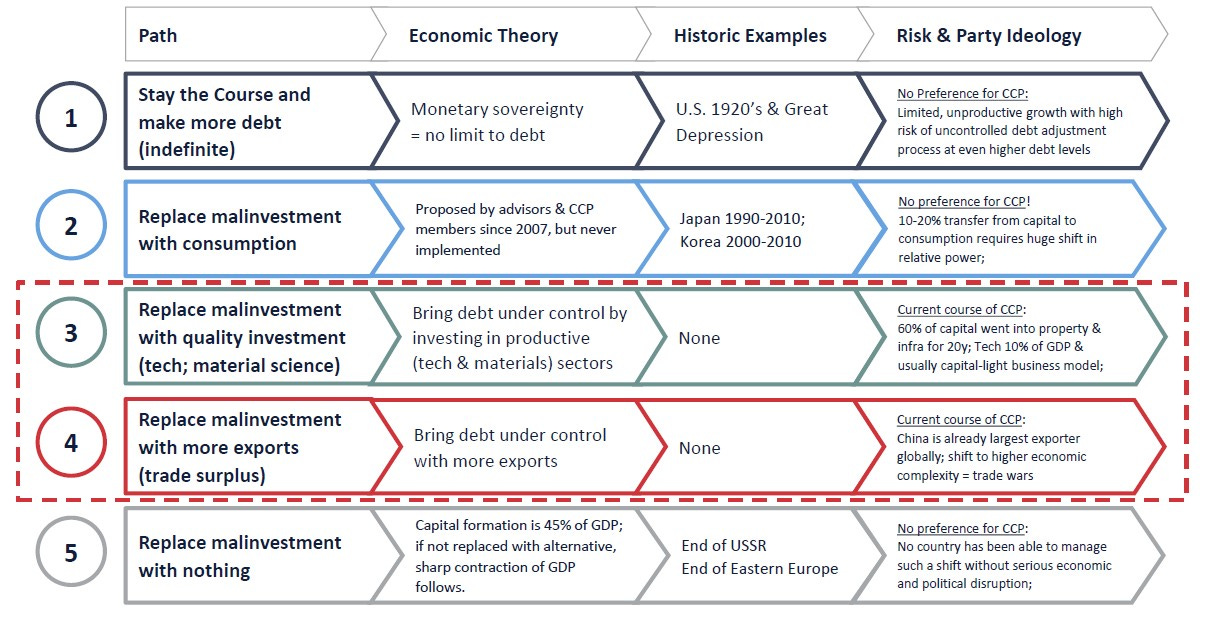

Aside from the current path, there are only four alternatives China can follow, each with its own requirements and constraints:

For now, China seems to pursue a hybrid of options number 3 and 4. We briefly assess all of them except path number 5, which everybody should understand intuitively.