The Death of Peace Treaties and Why Wars Often End Without Justice

Lesson 6

Lesson 6: The Death of Peace Treaties and Why Wars Often End Without Justice

The armistice signed on July 27, 1953, between the United Nations Command and North Korea reaffirmed the 38th parallel as the border between North and South Korea and created the four-kilometer-wide “Demilitarized Zone” (DMZ). The Military Demarcation Line bisects the “Bridge of No Return,” used for prisoner exchanges until 1968, when the crew of the USS Pueblo crossed it into South Korea.

The Korean War lasted just over three years, from June 1950 to July 1953. While fought on a divided peninsula, it was in fact the first hot war of the Cold War—a violent proxy confrontation between the democratic-capitalist West, led by the U.S., and the communist East, led by the Soviet Union. South Korea was supported militarily by U.S. and UN forces; North Korea by China, which sent hundreds of thousands of troops, and by the USSR, which supplied matériel, strategy, and legitimacy.

Because the war was a proxy clash between two worldviews, there was never a foundation for trust, let alone a peace process. Yet negotiations began relatively early, just over a year into the conflict. Formal talks opened in Kaesong in July 1951 and later moved to Panmunjom. Despite stalemate on the battlefield, they dragged on for more than two years, paralyzed by disputes over prisoners of war and the demarcation line.

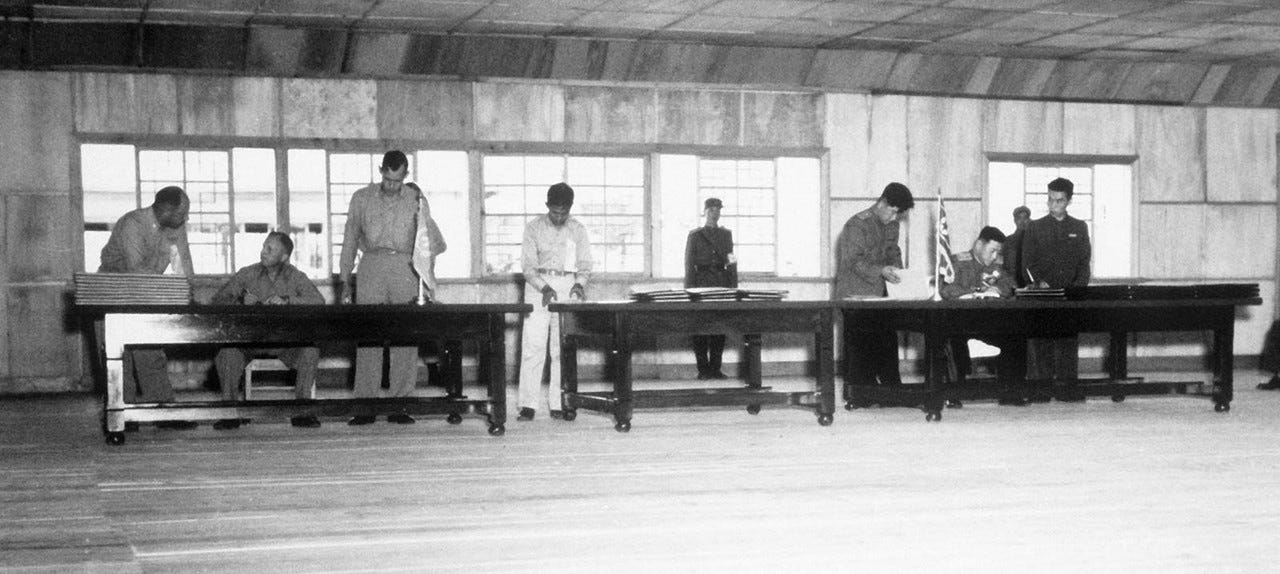

It took more than 700 meetings and nearly two years to negotiate the agreement—almost as long as the war itself. The signing of the armistice took just 12 minutes, conducted in silence at two separate tables so the delegations did not face one another.

The armistice contained operational provisions, notably prisoner exchanges: Operation Little Switch and Operation Big Switch staged the return of sick, wounded, and eventually all remaining POWs. But beyond this, the agreement was strikingly shallow. After 700 days of talks, the sides had failed to address any core political questions: no peace treaty, no normalization, no territorial settlement.

Many North Korean and Chinese prisoners refused repatriation, fearing persecution or worse at home. Their resistance became a major stumbling block and symbolized the deeper ideological divide. We see similar dynamics today in Ukraine, where defections and shifting loyalties complicate any prospect of peace.

The Korean settlement was a minimalist framework—closer to a UN resolution than a true bilateral accord. It reflected the smallest possible denominator: not a shared vision, but mutual exhaustion. Violence stopped, but the war never truly ended. To this day, there has been no Korean equivalent of the Tokyo Trials—no reckoning, no justice, no closure for victims. Remember this when you hear calls for a “just peace” in Ukraine.

Since 1953, the armistice has been violated more than 100,000 times. Even during global détente—such as the 1975 Helsinki Conference—tensions on the peninsula deepened. The frozen conflict became a “continuous nightmare”: artillery duels, assassinations, espionage, hijackings, and later, nuclear and missile tests. What was achieved in 1953 was not peace, but stalemate.

And that is why the Korean Armistice matters today: it offers a cautionary lesson to avoid false expectations as the world debates a “just peace” in Ukraine.