Skeena Gold & Silver: The Takeover Setup Is Now in Place

High Quality Gold AND Silver Asset with a Clear Pathway to First Gold

High quality asset with a clear pathway to first gold

Eskay Creek is a sizeable, high grade open pit project, grading roughly 3.5g/t gold equivalent. The mine plan targets around 450kozpa gold equivalent production in years 1 to 5 and roughly 320kozpa over a 12 year mine life. With AISC below US$900 per ounce in the feasibility study, Eskay sits in the rare category of high margin projects in a tier one jurisdiction.

What makes this story particularly interesting is that it is not a typical greenfield discovery that still needs to invent its infrastructure. Eskay is a brownfield re start with significant legacy assets, including road access, camp infrastructure, and most importantly an existing permitted tailings facility. This materially reduces both capex intensity and permitting loop risk, and it helps explain why management believes first gold in H2 2027 is achievable.

At today’s price, Skeena trades at a material discount to NPV, roughly 0.55 times, despite the project now having a clear catalyst pathway. Over the next 12 months, we expect further de risking to drive a re rating through three primary levers. First, final permitting milestones, including formal consent under the Tahltan framework, which until recently was the dominant political risk but isn’t anymore. Second, continued de-risking of capex and execution, including engineering progress and early works. Third, the potential buyback of the Orion gold stream, which would increase unencumbered leverage to gold and silver prices and improve equity quality.

In short, the project has moved from being a permitting and governance question to becoming an execution and valuation question, and that is where the market typically begins to pay most attention, and not just institutional investors, also the competition.

Eskay Creek, A Mine the Gold Price Left Behind

One of the cheapest and least risky ways to find a new gold mine is not to explore for gold, but to revisit old gold mines that were placed into care and maintenance because the gold price at the time no longer justified continued production. The industry refers to this as brownfield exploration, as opposed to greenfield exploration.

The advantage of this approach is simple. Historical mines come with data. Technical reports, drill logs, production records, and cut off grades already exist. In theory, if one takes a systematic view across closed gold mines and revisits the cut off grades that defined resources decades ago, it becomes possible to identify ounces that were uneconomic then but profitable at today’s gold prices. There is no magic involved. It is mostly arithmetic, discipline, and patience.

This is precisely what Walter Coles did in 2018. His background as a credit analyst at UBS in New York, perhaps, allowed him to see the forest for the trees at a time when gold prices were still relatively uninspiring. Somebody had to do the work, take a view, raise capital, and act. Walter did. Today, he owns roughly 4% of Skeena Resources, which seems well earned.

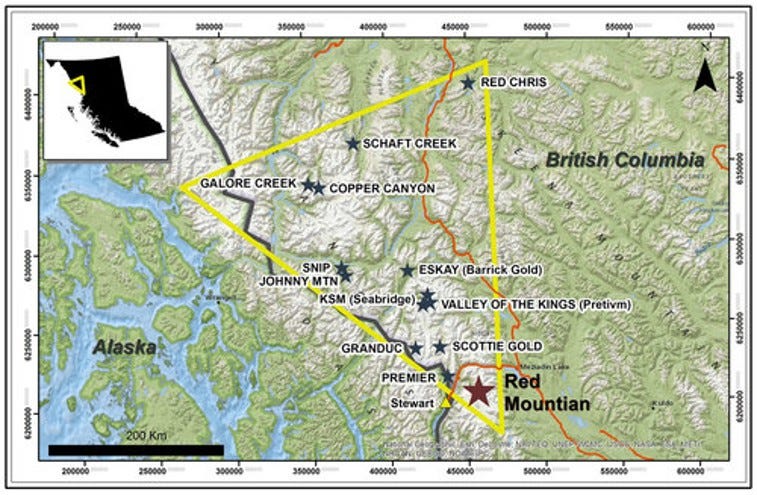

Walter identified Eskay Creek as a target within the so called Golden Triangle of northwestern British Columbia. The Golden Triangle is one of Canada’s most prolific mineral belts, host to both historic and current world class deposits. Seabridge’s KSM sits within the region. Brucejack, now owned by Newmont, is located there as well, along with its famously challenging high grade geology, which I have mentioned more than once by now.

Eskay Creek’s history stretches back to 1932, when prospector Tom Mackay first recognised the area’s unusual geological potential. Lacking modern exploration tools, Mackay relied on surface sampling and was unable to locate the core of the ore body.

It took more than fifty years for Eskay Creek’s true potential to be revealed. In 1988, a new exploration syndicate returned to the site under the guidance of legendary Canadian geologist Ron Netolitzky. Consolidated Stikine Resources, together with Murray Pezim’s Calpine Resources, initiated an aggressive drilling campaign. After 108 drill holes, it was hole 109 that changed everything, intersecting 27.2g/t Au and 30.2g/t Ag over 208m.

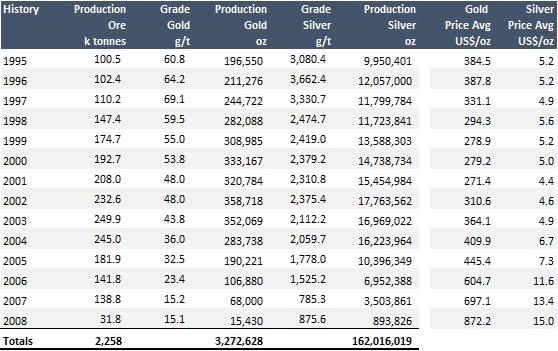

Following permitting, Eskay Creek entered production as an underground mine in 1994. Over the following 14 years, Eskay Creek produced roughly 3.3Moz of gold and 160Moz of silver at average grades of 45g/t Au and 2,224g/t Ag. It became the highest grade gold mine in the world and, by volume, the fifth largest silver producer globally.

In 2008, in the midst of the Great Financial Crisis, Eskay Creek ceased production and was placed on care and maintenance. Gold prices at the time were roughly US$872/oz. In simple terms, an underground cut off grade of 15g/t Au was no longer sufficient for Barrick Gold to justify continued mining. Despite its exceptional grades, Eskay Creek operated as a diesel and propane powered underground mine, which made it a high cost operation by the standards of the time.

After sitting dormant for several years, Walter Coles, through Skeena, secured an option to acquire Eskay Creek from Barrick Gold in 2017. In 2020, Skeena exercised that option and became the sole owner of the asset. In 2019, Walter also acquired the nearby Snip mine from Barrick, located west of Eskay Creek, for zero consideration plus assumed environmental obligations of roughly US$3m. Snip is another brownfield asset, formerly a high grade underground gold mine, and comes with extensive historical drilling and production data.

Below is a short clip of Walter Coles explaining how he approached the Eskay Creek opportunity, in conversation with Rick Rule in June 2024.

Before turning to the specific permitting framework at Eskay Creek, it is helpful to step back and clarify the geological risk differences between open pit and underground mining. That distinction explains not only why Eskay Creek looks the way it does today, but also why I deliberately structured the order of company discussions in this Substack the way I did.

We now turn to geology.

Open Pit versus Underground Mining

Open pit and underground mines fail for different geological reasons, and confusing the two is one of the easiest ways for investors to misprice risk.

Underground geology is dominated by geometry and continuity. Thickness matters because it controls dilution. Depth matters because it drives cost and technical risk. Length and continuity matter because stopes need to hang together. A deposit can be high grade and still be very difficult to mine underground if continuity breaks down or geometry becomes chaotic. This is why some underground projects with attractive grades struggle operationally despite looking compelling on paper.

Open pit geology is a different problem altogether. You are not chasing ore. You are averaging it at scale. The dominant risks shift away from shape and toward how the deposit behaves when reality deviates from the model.

For open pits, the most important geological variable is not the average grade, but the distribution of grade. Some deposits have tight grade distributions, where most material sits close to the mean. Others are highly skewed, where a small portion of high grade material carries a disproportionate share of value. In skewed systems, early years are especially vulnerable to disappointment if the block model is optimistic. This risk rarely shows up in feasibility studies, but it shows up brutally in market reactions once mining starts.

The second key variable is dilution sensitivity. Broad, disseminated systems tend to be forgiving. Narrow or structurally controlled systems mined in an open pit are not. A small amount of waste mixing can materially change economics. This is geology as margin risk.

Third comes geological complexity versus scale. Scale can absorb many issues, but it does not eliminate them. Complex geology increases grade control costs, reconciliation risk, and operational friction. Simple geology at scale is far more valuable than complex geology at scale, even at lower headline grades.

Fourth is metallurgical and geochemical personality. Sulphides, clays, deleterious elements, oxide to sulphide transitions, and water sensitivity are geological traits that matter far more in open pits than underground. They affect recoveries, operating costs, tailings behaviour, and closure risk. These features are real, persistent, and rarely emphasised by management teams.

Finally, there is what might be called geological forgiveness. Some deposits tolerate error. Others punish it. When grade, strip ratio, or recovery assumptions are wrong, forgiving geology bends. Unforgiving geology breaks.

For investors, the takeaway is simple. Underground geology is about whether ore can be followed. Open pit geology is about whether the model can survive contact with reality. High grade alone does not reduce risk. In open pits, it often concentrates it.