Running on Fumes: How refinery strikes and Urals economics threaten Russia’s oil output - and its regime

A data-driven look at Russia’s oilfields and refineries—and the risks to tomorrow’s barrels

Ration Cards in the “Petrostate”

Gasoline in Russia is being rationed from Kaliningrad to Vladivostok.

The state that styles itself an energy superpower can’t keep its own drivers on the road. In region after region, stations are limiting buyers to 10–20 liters per visit—if they have gasoline at all; elsewhere only diesel remains—which 98% of Russian passenger cars do not use. Russians move on gasoline.

Even pro-government outlets acknowledge ad-hoc curbs: Lukoil stations in Moscow banned fills into canisters and suspended certain fuel cards around Nizhny Novgorod to tamp down panic buying. This isn’t rumor; it’s on the record.

On some days, Russia’s refining capacity has fallen by nearly a fifth, with exports from key ports sharply curtailed. Crimea’s local newspaper reported that about half of Crimea’s gas stations have already run dry. But the situation seems also severe in the Far East and the Volga Federal District, where supply lines stretch thin and shortages bite hardest.

OMT Consult’s latest analysis measures the closing of petrol stations nationwide and suggests that only within the month of September 2.6% of all gas stations have closed down — a reduction by 360 petrol stations. They show that independent gas stations are overproportionally effected, with a uneven effect by region.

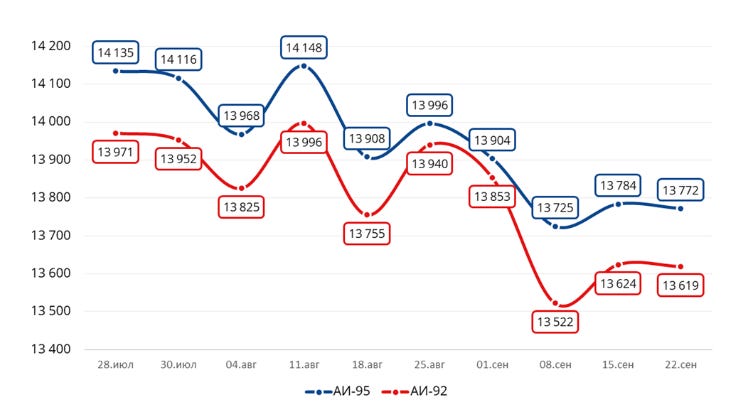

Prices tell a similar story, even though retail fuel is heavily managed and never a pure market signal. The exchange tape is. On the country’s main wholesale venue, the St. Petersburg International Mercantile Exchange (SPIMEX), AI-92 settled up 1.9% to 73,144 rubles per tonne—about US$0.66 per liter, US$2.50 per gallon, or US$105 per barrel at ₽82/US$. Those are hard prints—before retail taxes.

Volumes are the clincher. As Kremlin-friendly Kommersant noted in its 17 September 2025 market wrap, gasoline turnover fell to a two-year low: AI-92 sales dropped 21.7% d/d to 15,600 tonnes, AI-95 slipped 15.5% to 12,060 tonnes, and total gasoline sales slid 19.1% to 27,700 tonnes. Peak seasonal demand colliding with unplanned outages drains inventories fast—and the tape showed exactly that.

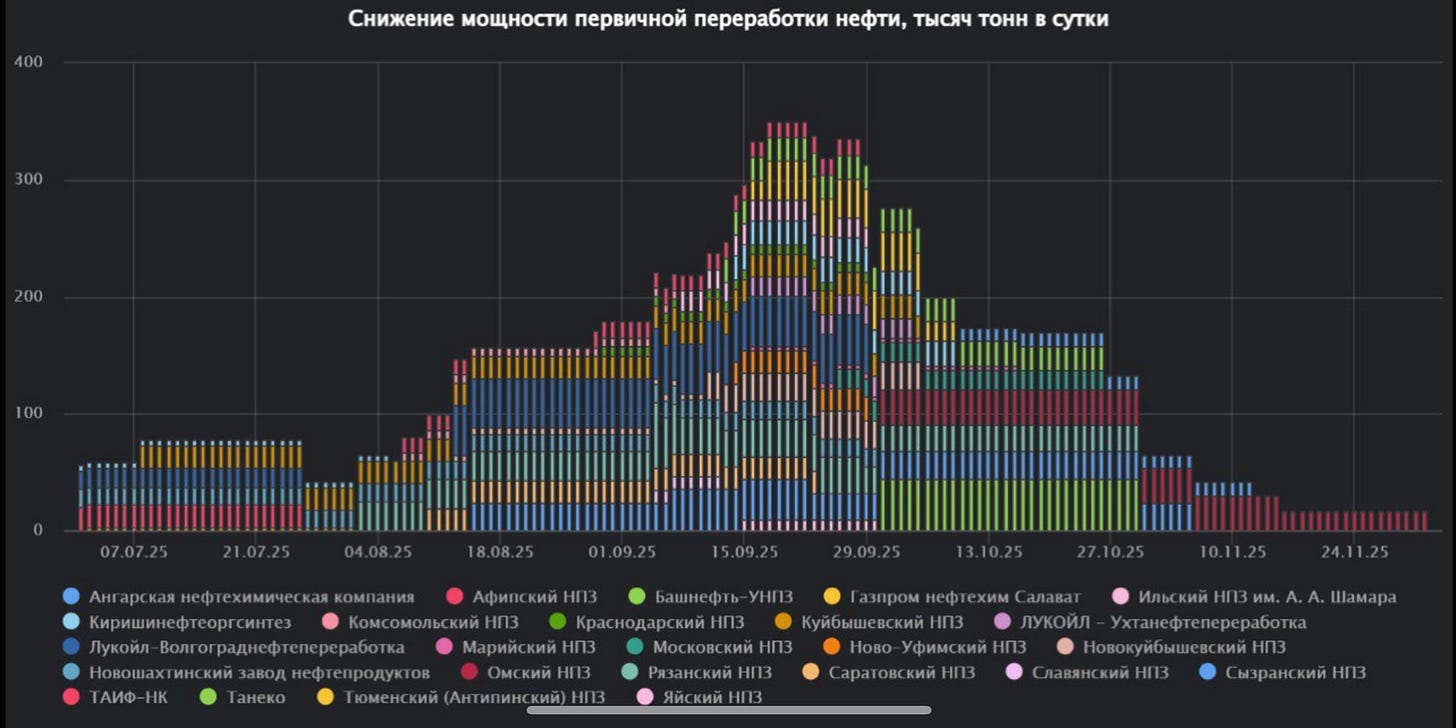

The capacity side is worse. In a 18 August 2025 Telegram post, Seala (Сиала) — a Russian energy-market analytics firm that compiles real-time stats on crude and product flows, refinery operations, and LNG — estimated that 226,000 tonnes/day of crude-refining capacity and 12,000 tonnes/day of condensate processing were offline nationwide at that time.

More recent reads are starker. Citing Seala’s plant-by-plant analytics, RBC Pro—the paywalled professional edition of the RBC business outlet—reported that by 28 September roughly 38% of Russia’s primary (CDU) refining capacity—about 338,000 t/day—was idle, while capacity suitable for producing gasoline and diesel fell 6% in August and a further 18% in September. On 1 October 2025, OilKapital repeated the same Seala-based figures: roughly 38% of primary units were down, i.e., this was not routine maintenance.

On 2 October, Seala (Сиала) clarified on Telegram that the “38%” figure reflected peak September downtime; by early October some units were returning from accident-related shutdowns. Their breakdown attributes 70% of September losses to drone strikes, with the balance to scheduled work. They also note that temporary restarts of older primary units skew yields toward fuel oil, leaving the gasoline balance much tighter than diesel.

Important caveat: the above October improvements are Seala’s forecast trajectory, not a statement that normal operations have broadly resumed.

My view? That trajectory is optimistic. Ukraine’s long-range drone campaign shows no sign of abating. On 4 October 2025, Ukraine’s General Staff listed fresh strikes, including Kirishinefteorgsintez near St. Petersburg. And Russian repair cycles are anything but straightforward under sanctions: parts, catalysts, control systems, and specialist contractors are all constrained. We unpack that later in this piece.

One more note on method. I pride myself on independent, data-heavy work and try to stay clear of propaganda—on both sides. Here, the exchange prints and Seala’s capacity math line up with what TV, Telegram, and even X are showing on the ground.

The fuel crunch in Russia is real—and it’s national, not local.

Minister Novak reacted as usual, with an extention of the diesel and gasoline export ban for producers — hardly surprising.

How Russians Move

If you want to grasp the drama of today’s shortages, start with a simple truth: Russian households run on gasoline.

The country counts roughly 55 million registered vehicles, of which ~46 million are passenger cars. Only a sliver of those cars are diesel. New-car data underline the point: diesel’s share of new passenger registrations has collapsed to about 1%; in the installed fleet it’s only a few percent. If you’re driving in Russia, you’re almost certainly burning gasoline.

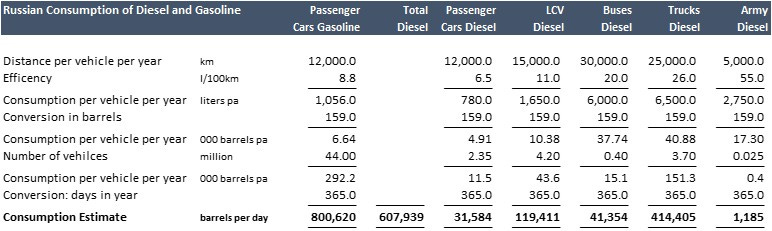

My table below does the heavy lifting, but here’s the headline: 0.801 mbpd of gasoline fuels private mobility, while 0.608 mbpd of diesel is consumed mostly by commerce, bus fleets, agriculture, and the military. Gasoline moves people; diesel moves the economy. That single split explains almost everything that follows.

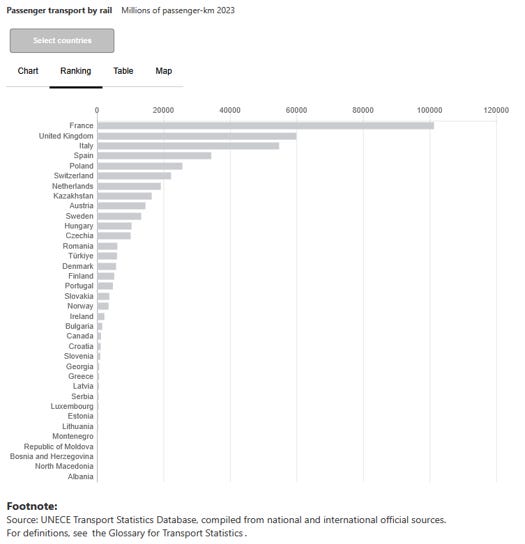

Now put that fleet into its geography. Outside Moscow and St Petersburg, public transport thins out fast. Intercity rail is engineered around freight first, passengers second; timetables are sparse, routings indirect.

Yes, there are seven metro systems, namely in Moscow, St Petersburg, Kazan, Nizhny Novgorod, Novosibirsk, Samara and Yekaterinburg. Yes, there are a handful of higher-speed corridors, notably Moscow–St Petersburg with branches toward Nizhny. But once you leave the big hubs, daily life is road-bound.

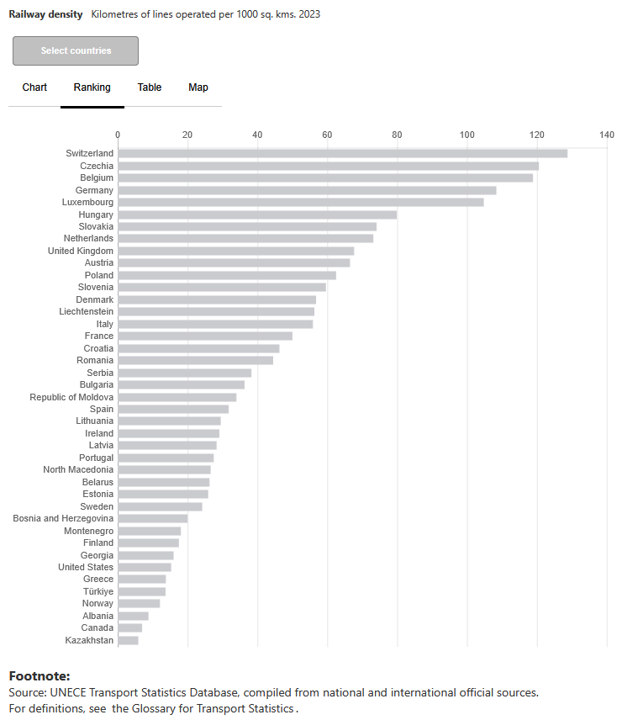

People often wave around “Russia has 85,000 km of railway” (and pundits love to confuse Moscow’s ornate metro stations with nationwide service) as if that settles the question. It doesn’t. Network density, frequency, and passenger capacity per person are what matter for everyday resilience—on those metrics, Russia lags far behind rail-first countries.

Measured as track per land area, Switzerland has about 129km per 1,000 km² (Germany 108; UK 131; France 43). The U.S. and Russia sit near the bottom—single digits per 1,000 km²— because their distances are continental and populations are spread out. Sparse track can still haul a lot of coal and containers. But it does not automatically move people.

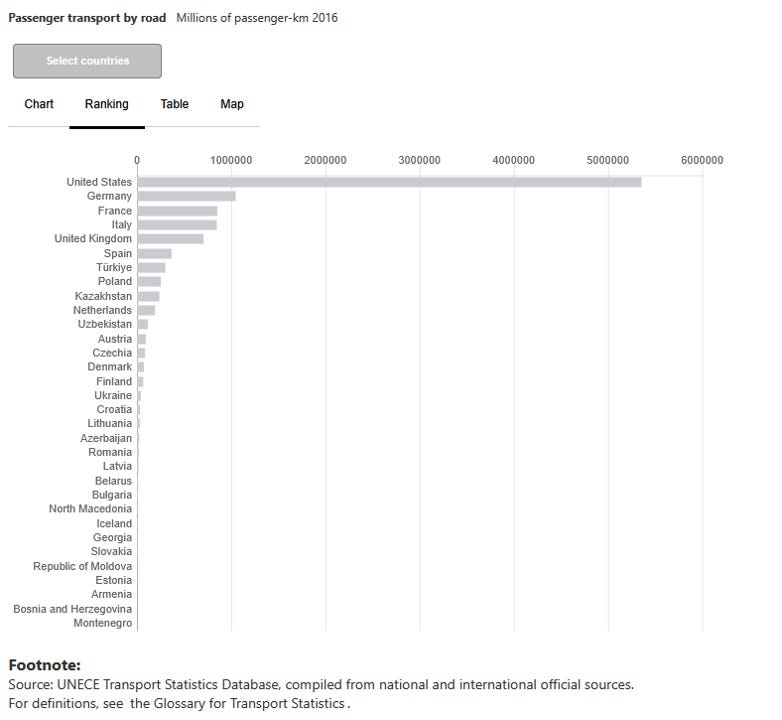

A cleaner like-for-like is passenger-kilometres per capita and offered capacity:

Switzerland (SBB) in 2024: 20.5bn passenger-km and 75.1bn seat-km offered. With 9 million people that’s 2,280 rail passenger-km per person and 8,340 seat-km of capacity per person. Rail is designed to be the default. The average Swiss takes 54 rail trips per year—and most ride the train twice a day for work.

Russia (RZD) in 2023: 136.3bn passenger-km (103bn long-distance; 33bn suburban). With 146 million people that’s 930 passenger-km per person — about 40% of Swiss usage. RZD does not publish comparable national seat-km, but given longer trains serving lower density, offered capacity per capita is well below Swiss levels. And none of that speaks to what happens after you step off the train in a far-flung oblast without trams, frequent buses, or reliable taxis. Believe me. I have been in the pampa many times. Not pretty.

That’s the structural backdrop to the shortages. Western Europe, Japan, South Korea—even China now—are built to move people by rail: short headways, dense stops, seamless hand-offs to metros and trams, and very high seat-km per capita. When petrol hiccups happen, life mostly continues; you take the next train.

Russia isn’t built like that. Distances are vast, settlement patterns thin, and outside a few cores the practical default is the road—for work, shopping, medical visits, and seeing family across an oblast. If gasoline is scarce, there isn’t a dense, high-capacity rail fallback to absorb everyday trips. In that sense - but only in this one - it is similar to the United States.

That’s why the current crunch cuts so close to the bone. Russians do not use gasoline for home heat or power—that’s district heat and natural gas. They use gasoline for mobility: getting to work, stocking shops and pharmacies, moving children and the elderly, keeping ordinary life ticking over.

So when you see ration limits of 10–20 litres per visit, wholesale exchange volumes hitting two-year lows, and capacity analytics showing a large share of CDUs down, translate that into lived reality: in a road-locked country whose households overwhelmingly drive gasoline cars, fuel shortages matter - immensely. And winter is arriving too, don’t forget.

In Soviet and post-Soviet writing, public transport is rarely a refuge; it’s a trial. Venedikt Erofeev’s Moscow to the End of the Line unfolds entirely on a suburban elektrichka that lurches, stalls, and seethes with overpacked carriages, hawkers, and drunks—a rolling purgatory where time and timetables dissolve.

The through-line is clear: outside a few privileged corridors, rail and trolleybus were something you endured, not a flexible backup that can absorb a sudden shift from cars to carriages. That’s why gasoline shortages translate into queues, cancellations, and fewer trips—not a standstill, but a grinding drag on everyday life. Let me say it bluntly: everyone tries to avoid public transport, if they can.

Let us now move to the supply side and drill down on some inconveniences.

Supply: Big Picture First

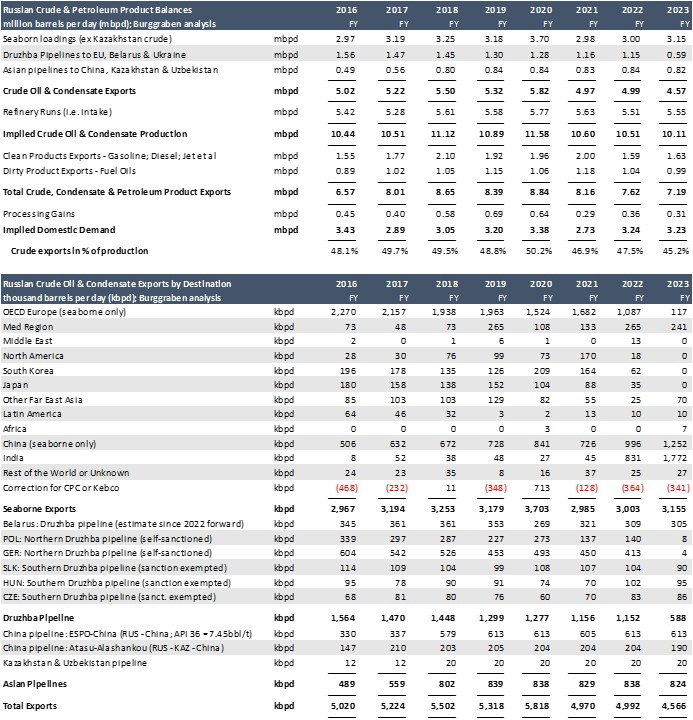

At Burggraben we track global crude and liquids balances closely. Even with wartime opacity, Russia’s oil system is still measurable.

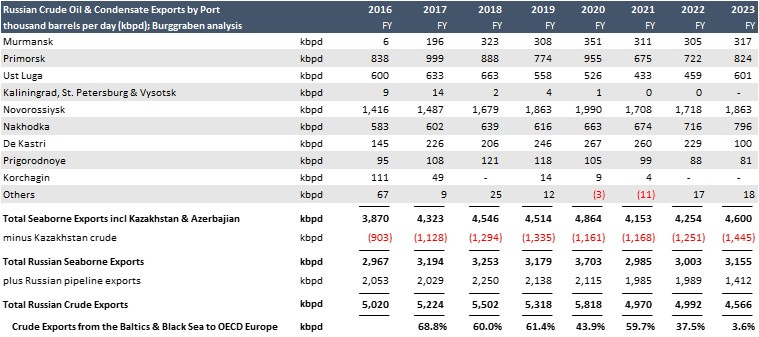

Russia produces roughly 10–11 mbpd of crude. About half leaves the country—moving either by sea or through Transneft’s pipeline grid (whose site is now geo-blocked for most Western IPs). The remainder, around 5.5 mbpd, is run through domestic refineries.

On destinations, the pattern is clear: India absorbs about 1.4–1.8 mbpd of Russian crude; China takes roughly 2.2–2.4 mbpd—about 1.7 mbpd seaborne, with the balance via pipelines feeding the ESPO/China network. Hold those anchors; they frame everything that follows and they’re harder (and more expensive) to find than you’d think.

The Great Consolidation of Russia’s Oil Empire

To our knowledge, Russia operates 24 active and relevant refineries.

Official counts sometimes reach 38, depending on how multi-site complexes are categorized. However, many smaller independents became irrelevant after Igor Sechin’s Rosneft consolidation crusade began in 2004—a campaign that transformed Russia’s oil sector from a patchwork of competing firms into a single, hierarchical system run by the security elite—the siloviki.

Catherine Belton chronicles this in Putin’s People: the siloviki turned oil and gas wealth into an instrument of political control. The destruction of Yukos, following Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s confrontation with Putin in February 2003, was the turning point: a fake auction of assets, legal theater for political expropriation.

The Bashneft raid in 2014 replicated the playbook: Sistema’s jewel seized, Vladimir Yevtushenkov confined, and in 2016 Bashneft formally folded into Rosneft. Markets noticed; trust never recovered.

By the late 2010s, consolidation was all but complete. Gazprom Neft retained limited operational autonomy. Novatek sits inside the President’s inner circle; its co-owner Gennady Timchenko is a regime pillar.

Lukoil remained the last bastion of genuine professionalism under Ravil Maganov: transparent, disciplined, commercially minded. In 2022, days after Lukoil’s board called for peace, Maganov fell from a hospital window and died. Officially, an accident. Unofficially, the end of corporate autonomy in the Russian oil and gas sector. As the great Garry Kasparov once wrote on X: “every country has its own mafia, but in Putin’s Russia, the mafia has its own country.”

By the time the siloviki finished re-wiring ownership, most of Russia’s refining sat inside state or state-aligned groups (with Rosneft roughly 40%). Retail prices were essentially administered—via excises, the ‘tax manoeuvre,’ the 2019 damper, and ad-hoc export curbs. The net effect wasn’t just higher prices over time; it was a system optimized for central control and export netbacks, not resilience. When a few big refineries go down, there are fewer independent suppliers, thinner inventories, and the shortage shows up at the pump fast.

The 24 That Matter

On that happy note, let’s focus on the 24 industrial-scale refineries that actually determine Russia’s gasoline and diesel supply.

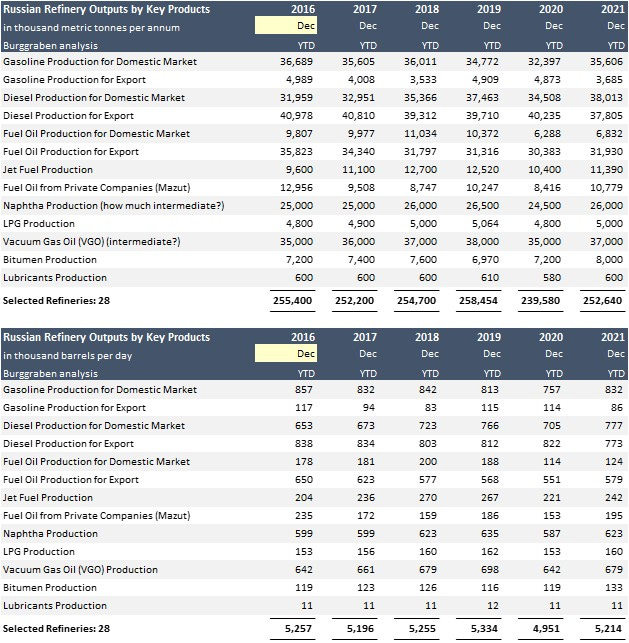

Between 2016 and 2021—when corporates still reported with some rigor—the system produced roughly 900,000 barrels per day of gasoline and about 1.5 million barrels per day of diesel.

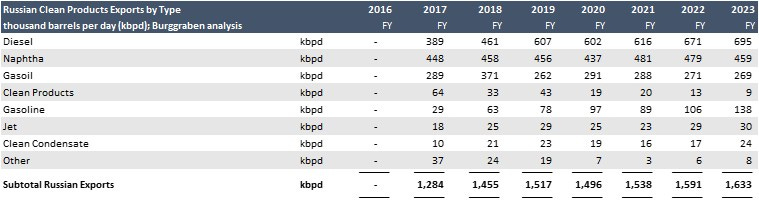

Those company tables are unusually useful because they split output into domestic sales and exports. That lets us check our demand math from the consumer side: around 800kbpd of gasoline burn at home, and roughly 750kbpd of diesel—leaving a diesel surplus on the order of 700–800kbpd for export.

The pattern is consistent year after year (excluding the COVID trough of 2020). Russia is roughly balanced on gasoline—able to cover passenger-car demand in normal times—but structurally long diesel. In practical terms, gasoline is the weak link; diesel carries the safety margin and will only become a bottleneck long after gasoline shortages break the system.

We can cross-check this with external flow trackers. Kpler’s seaborne data for 2021 show gasoline exports of 89kbpd versus 86kbpd in the company reports—almost a perfect match. On diesel, Kpler shows 695kbpd versus 773kbpd reported domestically; the gap is what you’d expect once you account for pipeline and rail movements to neighbors plus export timing differences.

Close enough to be statistically reassuring—and strong confirmation that the 24 refineries, not the long tail of “teapots,” are the ones that matter for national fuel balance. That’s the backdrop for everything that follows: a concentrated system, balanced on gasoline in good times, now being stress-tested by strikes on its conversion units.

And once again: Everything above is arithmetic, not attitude: company refinery ledgers cross-checked against independent flow telemetry and our internal balances—data that outlives the news cycle.

Structurally Short Gasoline

There is more.

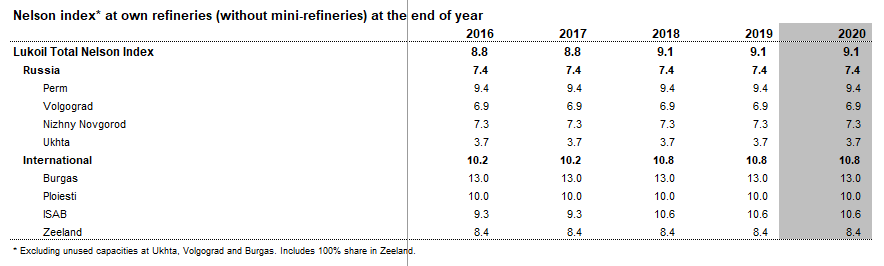

The imbalance isn’t just about outages; it’s baked into how Russia refines crude. On average, Russian plants are less technologically complex than their Western peers. Their Nelson Complexity Index (NCI) sits mostly in the 5–9 range; the U.S. system averages 9–11.

That number isn’t a vanity score. It tells you how much conversion muscle a refinery has—how far it can push heavy molecules “up” the value chain. Lower NCI means fewer and smaller high-conversion and upgrading units—fluid catalytic crackers (FCCs), hydrocrackers, reformers, cokers—and therefore less flexibility to tilt the yield toward light, high-value fuels like gasoline when the market screams for it. Configuration and capital intensity lock in those limits; you can’t just turn a valve and make more octane.

The Lukoil table (likely the best in Russia) makes this visible plant by plant. A mid-complexity refinery with limited FCC or hydrocracker capacity simply doesn’t have the hardware to swing its slate. If a hydrotreater goes down, even temporarily, gasoline production isn’t just lower; the quality of the blendstock (sulfur, aromatics, octane) becomes a bottleneck. And every bit of this gets harder when catalysts, sensors, compressors, and DCS components live under sanctions.

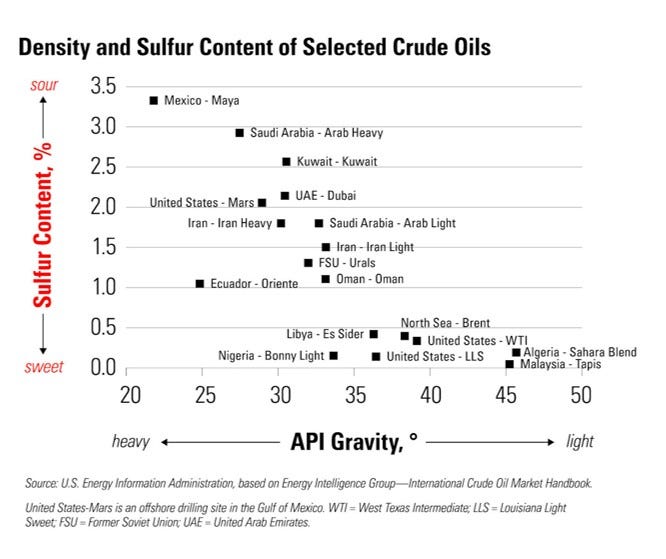

Then comes the feedstock - I usually like to call it the refinery diet. Most of the domestic system runs on Urals, a medium-to-heavy, sour grade (about 31–32° API, 1.3–1.4% sulfur). U.S. refiners, by contrast, process a lighter, sweeter diet—WTI 39–40° API plus very light shale streams blended with heavier Canadian barrels.

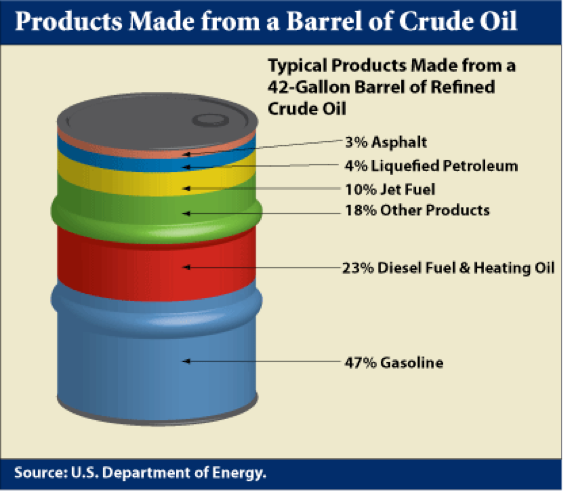

The chemistry is merciless: heavier in, heavier out. Urals yields more middle and heavy fractions—diesel, fuel oil, vacuum gas oil—while lighter crudes naturally produce more naphtha (the raw material for gasoline) and kerosene.

That’s why the yield tables look so different. In the United States, a barrel of crude reliably throws off 47% gasoline thanks to lighter feed and a conversion-rich system designed to maximize the octane pool. In Russia, the gasoline yield is closer to the low 20s because both the molecules and the machines lean toward diesel and residuals.

For decades, none of that was a problem. The Soviet and post-Soviet economies were diesel-heavy—freight, agriculture, construction, the military. Middle distillates were the sweat spot. Now overlay war-time attrition and that slate becomes a liability.

When Ukrainian drones hit conversion or treating units—FCC risers, hydrocrackers, naphtha hydrotreaters, reformers—the problem isn’t only physical; it’s chemical. You can sometimes limp along by running older primary units (CDUs/VDUs) to keep crude moving, but that pushes yields toward fuel oil and vacuum gas oil, not motor gasoline.

There’s also a quieter bottleneck insiders keep flagging: clean gasoline depends on hydrotreating — and hydrotreating depends on hydrogen. Russia’s Euro-5 sulfur cap (10 ppm) makes those units non-negotiable. When a hydrotreating/reforming train is down, or when catalysts and sanctioned parts are slow to arrive, crude can still flow through the CDUs — but the gasoline pool tightens anyway.

Of course, public reports don’t spell out “hydrogen shortages,” yet the pattern fits: sanctioned parts crippling a key gasoline unit at NORSI; repeated strikes on Ust-Luga cutting light blending components; and Seala/RBC Pro tallies showing sharp losses in capacity suitable for making gasoline and diesel. In refinery math, that’s how you run out of gasoline long before you run out of crude.

And that difference matters—immensely—when a handful of key conversion units go dark.

A laundry-room way to think about clean gasoline

Think of a refinery like a giant laundry.

The crude distillation unit (CDU) is the washer that sorts and spins out the big loads (light, middle, heavy “fabrics”).

The conversion units (cat crackers, hydrocrackers, reformers) are like heavy-duty cycles and stain removers that break down the tough stuff into smaller, more useful items.

The hydrotreaters are the detergent stage that actually gets things clean—they strip out sulfur and other impurities so the “shirts” (naphtha streams) are wearable as on-spec gasoline.

Now the quiet constraint: detergent = hydrogen. Hydrotreaters only work if there’s enough hydrogen flowing through the plant. If a hydrogen unit or a hydrotreating train is down (or starved of catalyst/spares), you can still run the washer (the CDU) and keep turning the drum—but what comes out isn’t clean enough to wear. In fuel terms: crude keeps arriving, but the gasoline pool tightens because you can’t desulfurize and finish enough blendstock to spec.

That’s why outages or sanction-snagged repairs in those “detergent” stages show up as gasoline shortages long before you “run out of oil.” The shirts are there; they’re just not clean enough to put on the rack.

Feedstock Geography: The Asian Lifeline

There’s a geographic logic to Russia’s refining problem that sits on top of the chemistry.

West of the Urals, the system runs on Urals blend—a medium, sulfurous crude that feeds most domestic refineries and the Baltic/Black Sea export grid. East of the Urals, the stream is ESPO (Eastern Siberia–Pacific Ocean), a lighter, cleaner barrel. ESPO’s specs (roughly 34–35° API, 0.5% S) make it naturally friendlier to gasoline/jet and light distillates than Urals (31–32° API, 1.3–1.4% S), which leans toward middle and heavy fractions. The molecules already predispose the product slate before a single valve turns.

But ESPO’s importance isn’t just chemical—it’s topology and politics. ESPO flows east through the dedicated ESPO pipeline to Kozmino (near Nakhodka), where it is loaded straight onto Pacific tankers. A smaller Pacific outlet, De-Kastri, ships light crude from Sakhalin projects (often blended and marketed separately), but for our purpose the point is the same: the Pacific system is plumbed to move light barrels out to Asia.

In 2023, those Pacific outlets together averaged on the order of 1.0 mbpd of crude exports, the overwhelming majority landing in China (with periodic parcels to Japan and South Korea when sanctions, insurance, and pricing aligned).

Set that against the western grid. Primorsk, Ust-Luga, St. Petersburg on the Baltic, Murmansk in the far north, and Novorossiysk on the Black Sea used to ship >2 mbpd of Urals into the EU and UK (note that mostly exports from Novorossiysk include exports from Kazakhstan too which are deducted below).

Post-sanctions, those flows collapsed and were re-routed mainly to India and Turkey—but only with longer voyages, higher freight, and a persistent discount to Brent to clear the barrels. The Russian west kept its heavy slate and its older refineries; the east kept its premium stream and direct Asian demand.

Two Russian Oil Economies

In effect, Russia now runs two oil economies—two crude diets with two distinct stacks of pipelines, refineries, and tanker routes.

West of the Urals sits the domestic-and-western system built around Urals: heavier, more sulfurous, and largely processed in older plants whose gasoline yields are highly vulnerable when conversion units go down—whether from strikes or maintenance.

To the east, the export system is built around ESPO, a lighter, cleaner blend that moves to Asia and typically clears at near-market prices.

Russian Oil Infrastructure

Pipeline physics make the split real.

Deliveries via the ESPO corridor to mainland China began in 2011. From the Russian grid, crude feeds a 942-kilometer China branch operated by CNPC and then into the northeastern pipeline network. Capacity started at 15 million tonnes per year (300kbpd), was later lifted to 20 million tonnes, and in 2018 China built a parallel line for another 15 million tonnes. Together, the two lines can move roughly 35 million tonnes per year—on the order of 700kbpd—directly into the Chinese system.

On the refining side, CNPC’s Daqing Petrochemical has been upgraded to process around 3.5 million tonnes per year of Russian crude. Daqing slots into an established northern fleet—Dalian, Liaoyang, Jilin, Jinzhou, Jinxi, Harbin, WEPEC—that runs ESPO blended with domestic grades. The ESPO share typically ranges from 15% to 50%. That isn’t trivia; it’s a reminder that a refinery’s “crude diet” is a capital choice: units, catalysts, and control schemes are tuned to a specific envelope of crudes, and the return on that tuning is earned back over years, not months.

That engineering reality sits on top of a commercial one. Moscow cannot simply redirect meaningful ESPO volumes to domestic refineries to chase higher gasoline output from lighter crude (higher API, lower density).

The barrels are plumbed east—to Kozmino on the Pacific and directly into China—under long-dated supply arrangements that took years to negotiate. Russia and mainland China signed a long-term supply contract in 2012 for roughly 15 million tonnes per year over twenty years, and similar commitments underpin the broader ESPO stream. Rerouting would fight both pipeline topology and the economics of plants already optimized for ESPO. Most of all, it would antagonize your most important buyer—the last partner the Kremlin can afford to alienate.

The practical implication is straightforward. If domestic gasoline shortages persist, the path of least resistance is not to starve the premium ESPO stream, but to import finished gasoline from China or other friendly refiners—if logistics permit.

Kremlin Math

There is more.

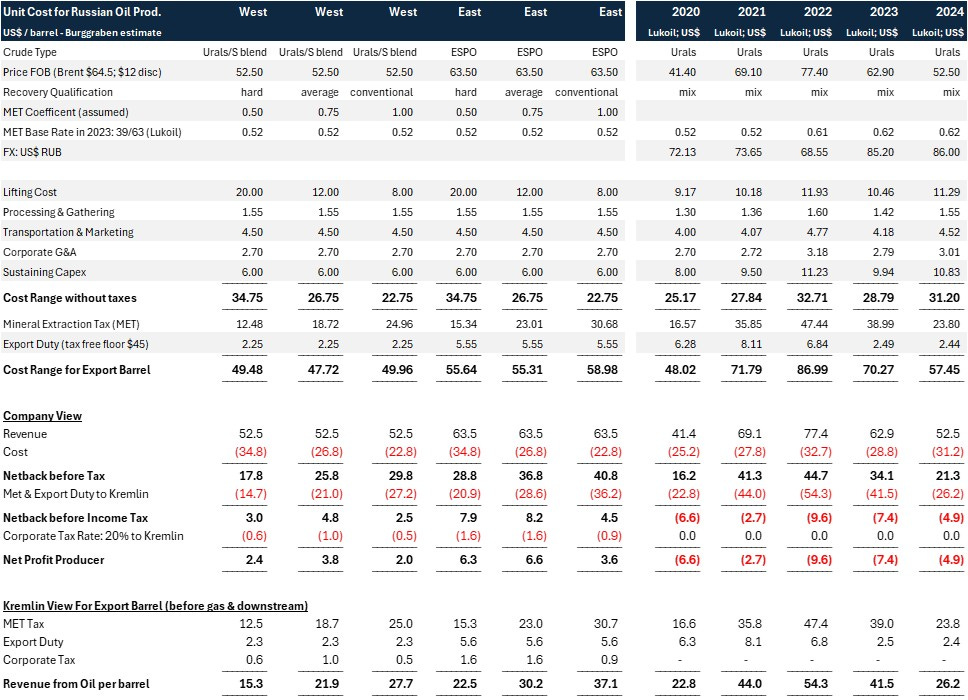

At $64 Brent as of this writing, ESPO has become the Kremlin’s financial lifeline for an illegal and self-destructing war. Nikolai Patrushev, the architect of that war, is unlikely to care about the arithmetic. But the arithmetic cares about him (and certainly about his son Dimitry), so let’s spell it out.

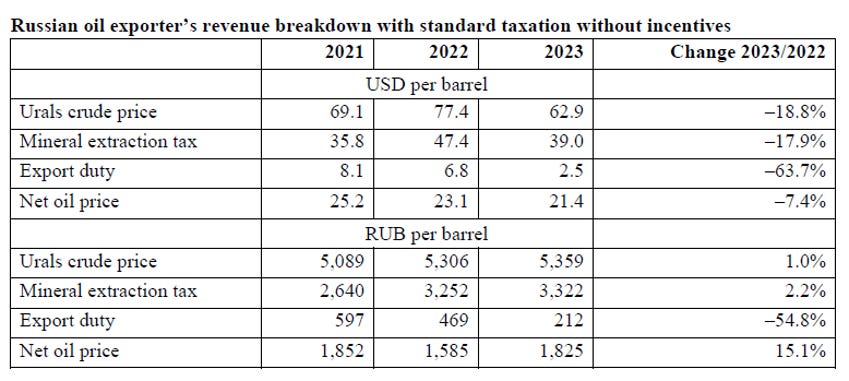

Sanctions and logistics frictions force Moscow to sell Urals at steep discounts to India and Turkey. In 2024, Bloomberg still quoted the Urals–Brent differential at roughly minus $12/b (see chart) — textbook monopsony: a few dominant buyers squeezing a captive supplier. The discount isn’t ideology; it’s just that Indian refiners like cheap.

Start with the Urals barrel. At Brent $64.5, less a $12 discount, you clear $52.5 FOB. Now walk down a realistic cost stack. Lifting runs $8–20/b depending on field and water cut; transport & marketing add $4–5/b; sustaining capex is at least $6/b but likely closer to $15 if you want tomorrow’s barrels to arrive; export duty contributes a couple of dollars on top of that. You’re quickly in the $25–35/b neighborhood before the Mineral Extraction Tax (MET).

Then the Kremlin raises the MET coefficients to keep the budget funded, and once you layer in export duties, war-risk freight, and insurance premia for the gray fleet, there isn’t much left to finance future barrels. As the Lukoil series showed up to 2023 (they stopped breaking it out in 2024), net profits on many Urals barrels collapse into the low-teens — and lower still on the tail of “hard-to-recover” barrels.

ESPO, by contrast, still clears near Brent in Asia — often at very narrow discounts or the occasional small premium. Call it $64.5 FOB at Kozmino against a broadly similar operating stack (with some east-side fiscal quirks). That leaves a pre-MET margin in the mid-30s per barrel. In other words: the premium eastern barrel pays for the war without immediately starving every upstream project that touches it as you can clearly see in my first table above.

The key takeaway is not that Gazprom Neft or Lukoil forgot how to run oilfields; it’s that the fiscal dial has been twisted to prioritize near-term budget cash over field economics.

The government could not afford to keep Urals-side MET gentle, so it didn’t. That props up the budget today, but it starves the upstream: less internal cash flow means lower reserve replacement, delayed maintenance, and a slower cadence of workovers and infill wells. It is the oil-patch version of eating your seed corn — the pipeline looks full now because you’re emptying the bins meant for next season.

None of this detonates tomorrow. It does, however, set the slope of the next few years. The more the state leans on MET and export levies to backfill the budget, the more Urals-weighted producers defer capex and cannibalize decline-mitigation work (e.g. reserve and production replacement). And Urals are the majority barrels Russia still produces. ESPO keeps the lights on; Urals determines whether the lights dim.

That’s the uncomfortable arithmetic behind the headlines: budget stability today bought with production instability tomorrow. Arithmetic masquerading as strategy — the kind that keeps pipelines full now by emptying fields later.

Which brings us to the status quo of the Russian oil fields.