Peace Is a Process

Lesson 9

Lesson 9: Peace is a Process

From Bolero to Dayton: Sarajevo’s Rise, Fall, and the Illusion of Peace

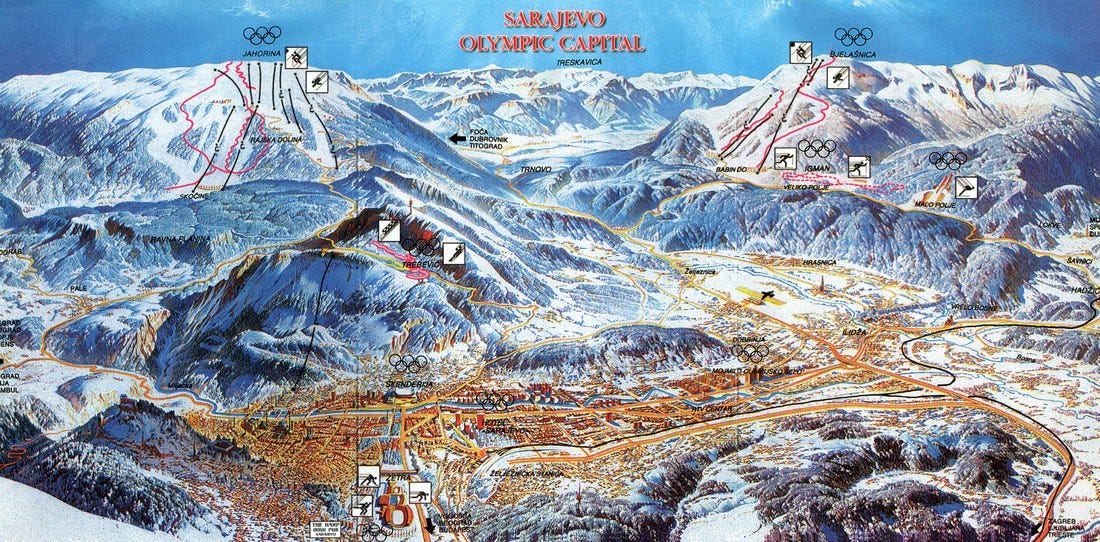

In February 1984, the world turned its eyes to Sarajevo—in admiration. Then part of socialist Yugoslavia, the city hosted the Winter Olympic Games under the stewardship of the late Spiljak Presidency. For two radiant weeks, Sarajevo became a rare symbol of openness during the Cold War. Even Western sponsors like Coca-Cola, Kodak, and Miller Brewing poured money into the biggest sporting event ever staged in a communist country outside the Eastern Bloc — a novum.

The Games modernized Sarajevo’s infrastructure, brought in more than $100 million in spending, and ignited a lasting love of sport. One unforgettable moment came when British ice dancers Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean performed their legendary Bolero, earning twelve perfect sixes and captivating the world. Sarajevo—nestled among snowy mountains—had never seemed more radiant. For a moment, it was a city of coexistence: where Bosniaks, Croats, and Serbs, Muslims, Catholics, and Orthodox Christians lived side by side, and where East and West mingled with elegance and grace.

But sadly, Sarajevo did not survive the decade.

The Collapse of Yugoslavia, the Road to War and the Dayton Agreement

In the early 1990s, as communist regimes crumbled across Eastern Europe, the multiethnic Yugoslav federation began to unravel. Originally created after World War I from the remnants of the Austro-Hungarian Empire as the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes—and later rebranded Yugoslavia—the state had long struggled with internal divisions. Although the formation of Yugoslavia in 1918 was framed as a union of South Slavic peoples, there was no popular referendum in 1919 to approve this historic merger. Slovenians and Croats, emerging from the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, sought self-determination and initially supported the idea of unification—but under expectations of equality and federalism. Instead, they were absorbed into a centralized monarchy dominated by the Serbian royal house, without direct input from the people.

What followed was not a consensual union but a top-down political construct shaped by elite negotiation and geopolitical urgency. This lack of democratic legitimacy sowed disillusionment early. Some now argue there was never a genuine foundation for a unified “Slavic” state—only an uneasy balance, held together first by monarchical centralism, then by Tito’s charisma and Cold War geopolitics.

Marshal Josip Broz Tito, who led Yugoslavia after World War II, forged a communist federation from this fragile foundation. Through a mix of authoritarianism, decentralization, and strategic neutrality between East and West, Tito held the union together for over four decades. But with his death in 1980 and the collapse of communism a decade later, long-suppressed nationalist forces re-emerged with a vengeance.

When Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence in 1992—following similar moves by Slovenia and Croatia—the Yugoslav People’s Army and Serb nationalist forces, backed by Belgrade, responded with force. Their goal: to carve out a “Greater Serbia” through territorial conquest and ethnic cleansing.

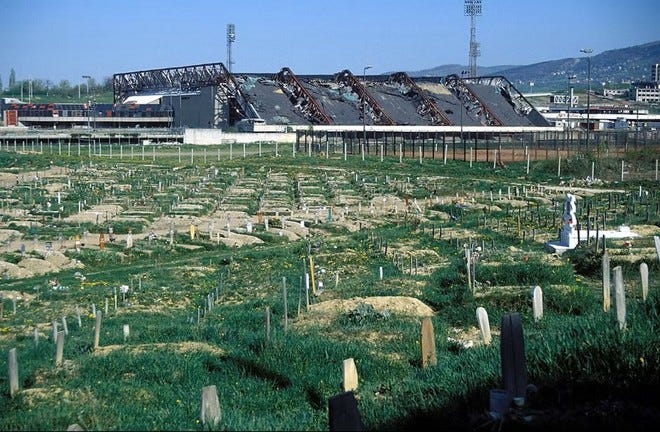

Bosnia descended into war. The capital, Sarajevo, was surrounded by Bosnian Serb forces in a siege that lasted nearly four years. What followed was one of Europe’s darkest chapters since 1945: ethnic cleansing campaigns, concentration camps, and the systematic destruction of towns and communities—often under the command of indicted war criminals like Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić. More than 100,000 people were killed, the vast majority Bosniak Muslims. In July 1995, over 8,000 men and boys were executed at Srebrenica, the worst genocide in Europe since the Holocaust.

The war ended not with reconciliation but exhaustion—and foreign intervention. After weeks of NATO airstrikes against Serbia under U.S. leadership, the warring leaders were flown to Dayton, Ohio, where they were locked inside an American air base for three tense weeks. Out of this came the Dayton Peace Accords, signed in November 1995.

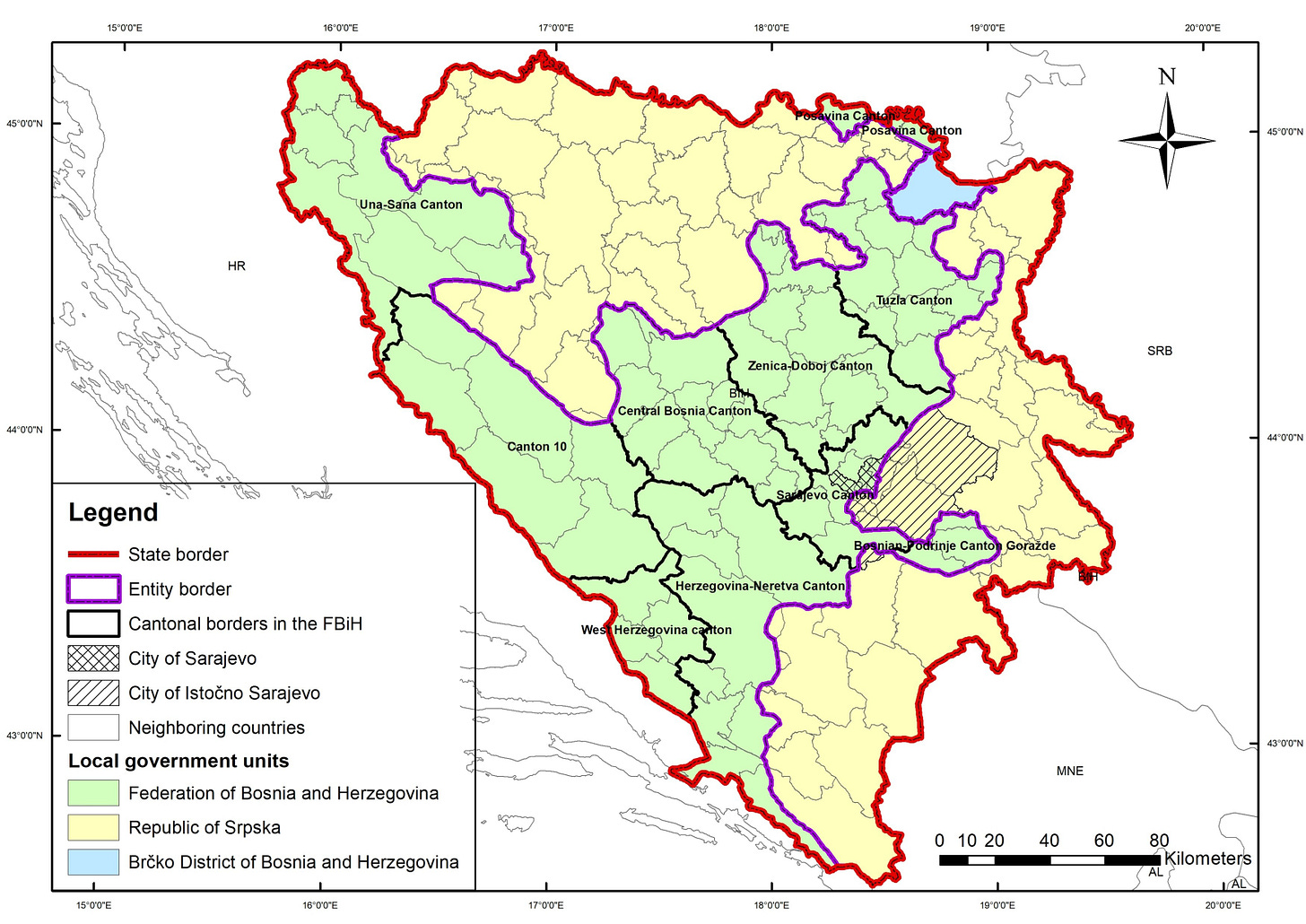

A Peace of Entities

Dayton stopped the killing (which was phantastic), but sadly it froze Bosnia into a constitutional straitjacket. The country was cleaved into two “entities”: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, where Bosniaks (around half the population) and Croats (about 15%) dominate, and Republika Srpska, home to most of the country’s Serbs (roughly 31%). Each entity was granted sweeping autonomy. There is no hard border, yet lives are lived apart. Schools teach different histories, children grow up in parallel worlds, and mixed marriages—once common in Sarajevo—have all but vanished.

The state structure is a monument to over-engineering. Bosnia’s 3.3 million people live under a labyrinth of governance: two entities, ten cantons, fifteen parliaments, six presidents, three governments with 160 ministers, 760 deputies, and a three-member state presidency that rotates every eight months. It is government designed to prevent domination—but also to prevent progress.

The Protectorate Within

To enforce this peace, the international community created the post of the High Representative, appointed by the UN Security Council and backed by the so-called “Bonn Powers”: the ability to impose and annul laws, to appoint and sack officials, even to rewrite constitutions. Since 1995, every High Representative has come from an EU country, with American deputies at their side. For three decades, they have ruled like viceroys, stepping in whenever Bosnia’s fragile system teetered.

On paper, this was meant to ensure stability. In practice, it entrenched dependency and corruption. The presence of an all-powerful international arbiter allowed local elites to avoid responsibility, to exploit veto powers, and to paralyze reform. Bosnia became less a democracy than a managed protectorate, where the final word rested not with citizens, but with foreign supervisors. The Dayton Accords promised peace with justice; what they delivered was peace without ownership.

The Strongman of Republika Srpska

Few have exploited this arrangement better than Milorad Dodik. Once praised by Madeleine Albright as a “breath of fresh air,” he is now Bosnia’s most notorious nationalist and likely the sprider of a corrupt empire web. “I am a Serb… Bosnia is only my place of employment,” he declared the day after his inauguration as head of state. Dodik has built his career by railing against the very system that sustains him—mocking Bosnia as illegitimate, flirting with secession, and courting Moscow.

He welcomes Kremlin-linked biker gangs to Banja Luka, endorses Russia’s annexation of Crimea, and promises that Republika Srpska (RS) is a “state-in-waiting.” When scandals or fiscal crises threaten him, he escalates secessionist rhetoric to rally his base. Sanctioned by Washington, tolerated by Brussels, he thrives on the dysfunction Dayton created. By institutionalizing ethnicity, the Accords rewarded politicians who divide rather than unite.

In many ways, Dodik’s story is a familiar one in Eastern Europe, that of a politician changing his stripes when the moment suits, and courting Russia as an ally (think Victor Orban or Robert Fico). But here in Bosnia, the stakes are higher, not just for the people who live here, but for the legacy of a significant American foreign-policy achievement, too. By taking aim at the Bosnian state, Dodik is, in effect, targeting the Dayton Accords, one of the signature peace deals of the 20th century.

Why does he do it? Simple. Deception. It’s always deception from corruption. As Michaela Ulbrichtová writes in her article titled “Milorad Dodik’s metamorphosis and the hijacking of the Dayton peace agreement”:

But what is the real logic behind Milorad Dodik’s current political strategy? Is he again seeking to divert attention from his corruption scandals and simultaneously gain additional political credit from media publicity, or has his political game gained more threatening contours in light of global geo-political changes and his close ties with the Russian Federation?

His political dominance is built on systemic looting: state institutions captured by loyalists, public contracts awarded to cronies, and media and civil society muzzled through legislative intimidation. Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index paints a bleak picture: Bosnia scored 33/100, ranking 114th out of 180 countries—the worst in the Western Balkans and second-worst in Europe after only Ukraine and Russia. In an indictment of Dayton's design, these abnormalities have thrived under the cover of institutional paralysis and international cautiousness.

The latest? In April 2025, Bosnia’s State Court and Prosecutor’s Office sought international arrest warrants for Dodik and RS assembly speaker Nenad Stevandić, accusing them of subverting constitutional order. They had declared daytime police and judicial authorities null within RS—an egregious legal defiance. Interpol ultimately rejected the request, deeming it politically motivated.

By June–July 2025, Dodik was convicted in absentia and sentenced to one year in prison and a six-year ban from political office. His courtroom absence was emblematic; he rejected the verdict outright, labeling it politically engineered. He continues to defy the ruling with legislative maneuvers that bolster RS autonomy and deepen the constitutional crisis.

This conflict has triggered what analysts now call Bosnia’s gravest political crisis since Dayton, exposing the fragility of its institutional architecture—and the ease with which a single figure can weaponize it

Clearly, His Excellency Christian Schmidt lacks either the courage or the mandate to end Dodik’s corruption theatre. For all his sweeping powers under the Bonn framework, he acts more like a cautious administrator than a determined guardian of peace. Instead of decisive action, we get stern communiqués and vague warnings to Brussels—that Bosnia is once again “at risk of breaking up.”

The risk isn’t theoretical. It’s already unfolding. And Schmidt, despite his authority, seems to believe that appeasement is still a viable strategy. But appeasement never works with strongmen. It emboldens them.

In trying to avoid destabilization, the High Representative preserves the very dysfunction that makes collapse more likely. And in doing so, he confirms what many in Bosnia already feel: that the international community no longer has the will—or perhaps the interest—to confront the very forces unraveling the peace it once imposed.

Protest Without Change

Ordinary Bosnians see through the illusion and corruption. They have taken to the streets again and again, only to be met with inertia.

In 2014, as many as 40,000 people protested across 20 cities, torching government buildings in outrage over poverty and failed privatizations. Between 2018 and 2019, Banja Luka saw weekly rallies under the slogan “Justice for David,” after a young man’s suspicious death exposed state complicity. In 2023, more than 10,000 marched against gender-based violence after a femicide was broadcast live on social media. And in 2025, students in Sarajevo flooded the streets, blocking roads and demanding accountability for corruption and disaster mismanagement.

Each protest began with a spark but revealed a deeper truth: Bosnia’s peace is shallow. The war is over, but the system that replaced it works for corrupt elites, not citizens.

A Laboratory of Illusions

Anthropologist Larisa Kurtović calls Bosnia a “political laboratory”—a place where Western liberal powers tested peacebuilding models, declared victory, and moved on. For a brief moment after Dayton, Bosnia was the showcase of liberal internationalism. But as global attention shifted—first to Iraq, then to the financial crisis, then the Arab Spring—Bosnia slipped into the margins. What remained was a hollow peace: stable enough to endure, fragile enough to stagnate.

What makes Kurtović’s critique especially urgent is her challenge to the geopolitical imagination itself. She urges us to move beyond the illusion that peace can be engineered through ready-made models or universal norms. Lasting peace, she implies, cannot be imposed from above—it must emerge from context, memory, and lived experience. But the international community, eager to claim success, never invested in that kind of transformation. Instead, Bosnia became a testing ground for “new forms of technocratic reason”—tools that often deepened existing fractures rather than healed them.

Kurtović’s essay is not just about Bosnia—it is a warning. It asks what happens when peace becomes a product, exported from distant capitals and tested on societies shattered by war. In a world still addicted to quick geopolitical fixes, her words are clear: peace without justice is no peace at all. And forgetting the unfinished past only guarantees its return.

Three decades later, Bosnia remains frozen in the scaffolding of Dayton. It is held together not by trust or reconciliation, but by annexes, vetoes, and international oversight. Its people live parallel lives. Its leaders exploit division. A peace designed to prevent domination has bred paralysis. A system meant to encourage equality entrenches separation. And an international protector meant to guarantee justice now preserves dysfunction, afraid to dismantle the house it was sent to rebuild.

The Orphan of Dayton

Bosnia today is less a country than an orphan of the Dayton order—a post-war teenager never allowed to grow up. Held in a constitutional straitjacket for nearly three decades, the state remains unreformable and paralyzed—yet paradoxically, reform is its only hope if it’s ever to join the European Union.

The very structure meant to guarantee peace has instead become a perfect playground for nationalist strongmen and systemic corruption. Leaders like Milorad Dodik have no genuine interest in European integration—they thrive on division. Public life operates like a patronage racket: loyalty to the ruling parties is traded for jobs, permits, and favors. Citizens, not ideology, are the real losers in this market of influence.

Meanwhile, the High Representative hovers like a distant guardian angel—equipped with sweeping Bonn Powers, yet increasingly reluctant to use them. His role is to ensure stability, but not to challenge the roots of dysfunction. He preserves the scaffolding of Dayton, but never clears the space to build something new. In practice, Bosnia is trapped—not collapsing, but unable to grow. In chess terms, it is not in checkmate, but in pat—a stalemate in which no one wins and no one can move.

The paradox is partly bureaucratic: to shake the system would risk the very mandate the international community still clings to. Why dismantle the rules of the game, when the game justifies the referee’s existence? What this leaves behind is a suffocating climate—not one lacking talent or energy, but the conditions to use them. Entrepreneurship is choked by a political class that acts like a mafia: blocking permits, hijacking contracts, and strangling competition. Prosperity would empower people—and that, more than anything, would endanger the elite’s grip on power.

The Dayton Accords promised peace with justice. What they delivered is peace without ownership. And thirty years later, Bosnia lives in managed silence, waiting not just for stability, but for permission to grow up.

From the Stagnation of Dayton to the Promise of European Accession

Bosnia’s political paralysis today is no accident but the direct consequence of the Dayton Accords—a bureaucratic monster designed to freeze peace but inadvertently freezing progress, reform, and national cohesion as well. While Dayton may have prevented outright collapse, it created a system rigged to reward division and empower corrupt strongmen like Milorad Dodik. The very architecture intended to guarantee stability has calcified Bosnia’s political dysfunction, trapping its people in a state of managed silence and suffocating stagnation.

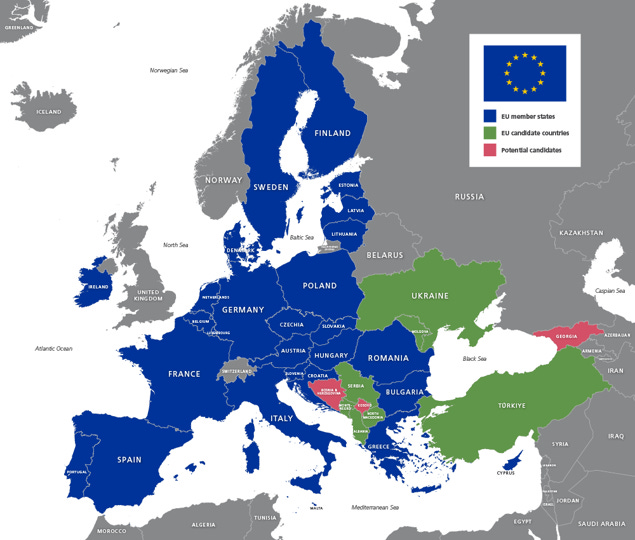

Yet amidst this bleak landscape, a new hope flickers on the horizon: European Union integration. Bosnia’s path towards EU accession offers not just a procedural process, but the potential to finally break free from the deadlock of Dayton’s failure and the entrenchment of corruption. The Stabilisation and Association Agreement (SAA) signed in 2008 and fully in effect by 2015 marked the first concrete step towards closer ties with Europe. The granting of candidate status in December 2022 and recent recommendations by the European Commission to open accession negotiations signal a cautious but growing momentum for reform and alignment with EU norms.

However, the road ahead remains fraught with political obstacles—most notably from Republika Srpska’s leadership, which continues to weaponize ethnic division and reject the very institutions meant to guide Bosnia towards the European future. The entity’s recent legislative moves to annul decisions linked to the High Representative and halt EU-related processes reflect a defiant resistance to integration, fueled by nationalist rhetoric and secessionist threats from Dodik. Why doesn’t his Excellency just take him out?

The EU’s response has been unequivocal: the sovereignty, unity, and constitutional order of Bosnia and Herzegovina must be respected, and political actors must recommit to the difficult reforms necessary to advance the country’s accession path. European integration offers a chance not only to modernize Bosnia’s institutions but to replace Dayton’s brittle peace with a more durable social contract—one built on rule of law, democratic accountability, and economic opportunity.

Whether Bosnia can seize this opportunity depends on overcoming the deeply entrenched political culture that Dayton helped create—a culture that rewards division, protects corruption, and fears the consequences of genuine change. The question remains: can Bosnia leverage the EU accession process to finally break its cycle of dysfunction and reclaim its future?

European Union — A Peace-Building Supranational Project

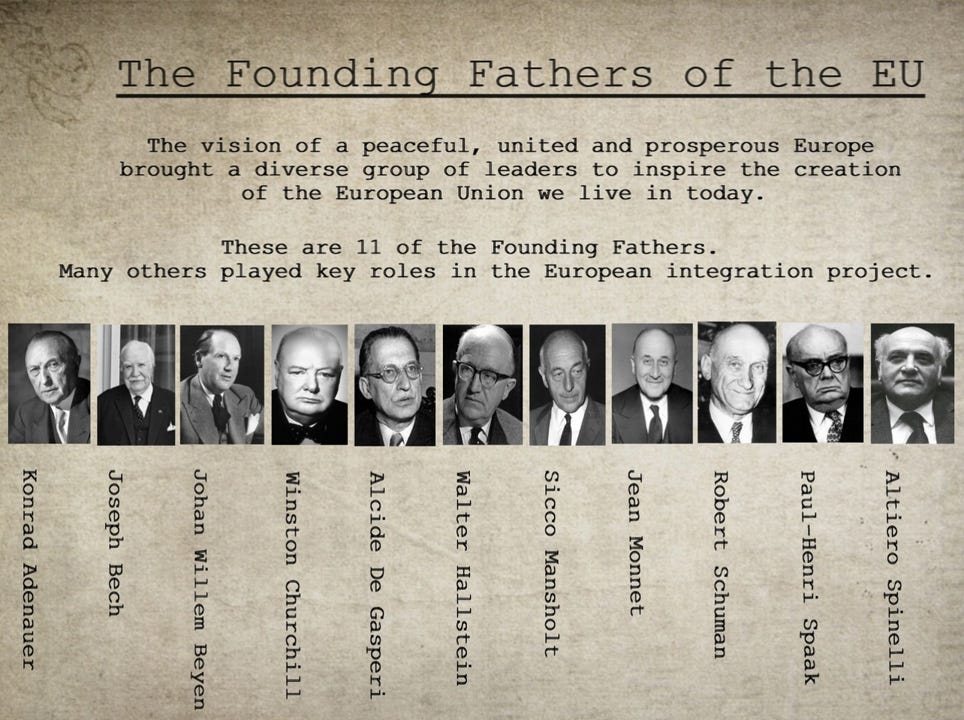

In the aftermath of World War II, Europe’s leaders embarked on an ambitious and visionary project: to build lasting peace by transcending centuries of conflict through cooperation and integration. The European Union (EU) was born from this ideal, evolving from economic cooperation into a political and security union designed to bind nations so closely that war would become unthinkable.

The project’s origins trace back to the landmark Schuman Declaration of 1950. French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman famously proposed pooling the coal and steel industries of France and Germany—historical sources of conflict—into a shared community that would make war “not merely unthinkable, but materially impossible.” This European Coal and Steel Community, established in 1951 by six founding countries, laid the foundations of the supranational institutions that would evolve into today’s EU.

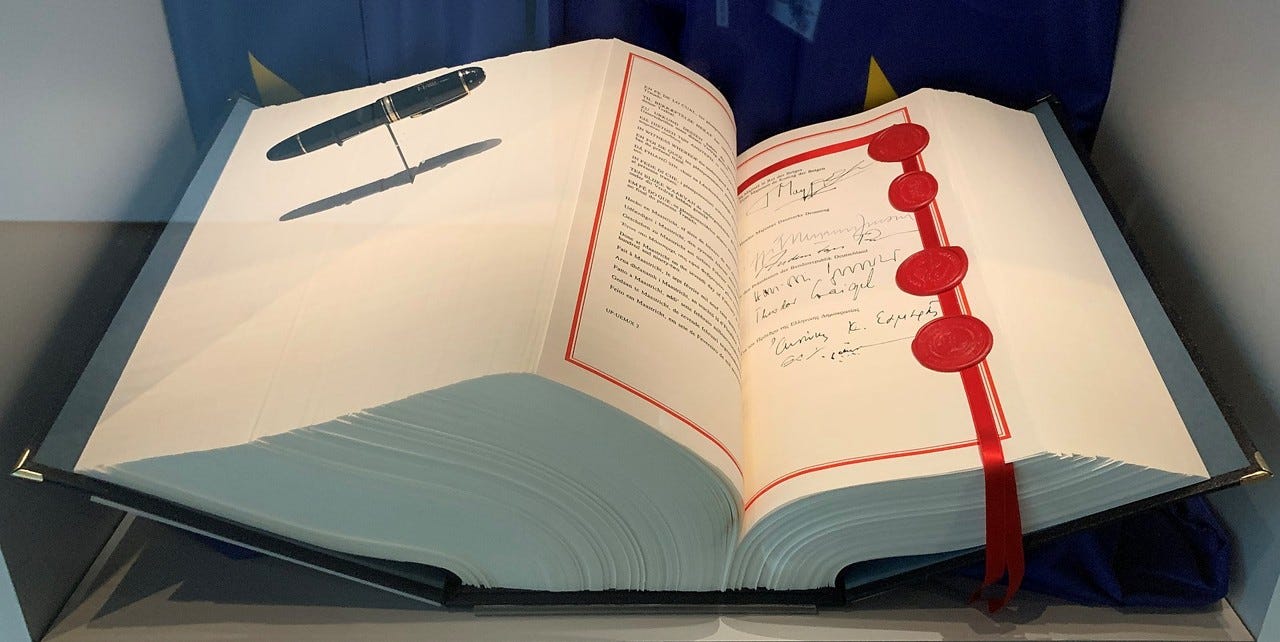

Peace is enshrined as a core value in the EU’s legal and political framework. Article 21(2)(c) of the Treaty on European Union commits the bloc to “preserve peace, prevent conflicts and strengthen international security,” reflecting its deep-rooted identity as a peace project.

The Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), formalized in 1993 with the Maastricht Treaty and reinforced by the 2009 Lisbon Treaty, enshrines the EU’s foundational commitment to peace. It advances democracy, human rights, the rule of law, and the peaceful resolution of conflicts as pillars of European cooperation.

A famous quote that describes the European Union as a peace project comes from Chancellor Helmut Kohl. On December 15, 1991, at the CDU party congress in Dresden, he said:

„Die deutsche Einheit, die europäische Einigung waren immer unsere Visionen. Jetzt realisieren wir die europäische Einigung, weil es dem Frieden, weil es der Freiheit, weil es der Zukunft dient.“

(“German unity, European unification have always been our visions. Now we are realizing European unification—because it serves peace, because it serves freedom, because it serves the future.”)

Without the EU’s gravitational pull and its conditionality mechanisms, it is difficult to imagine many Eastern European countries—certainly Romania and Bulgaria—achieving the political and institutional reforms needed for stability, prosperity, and democratic consolidation, however fragile those gains may still appear. The European project did not merely offer a vision of peace; it created the structure and incentives necessary to begin building it.

I have personally witnessed this in practice—having dealt with significant civil court proceedings in Romania, I can attest that, despite its imperfections, the system works. That would have been unthinkable without the reforms driven by EU accession. No, it does not extinguish corruption—but it does contain it, and it allows for steady economic and institutional progress. That alone — and for all its flaws — makes the EU model not just a peacekeeping force, but a mechanism for transformation.

The EU’s response to shifting global realities has also involved expanding its security ambitions. The Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) seeks to foster a European strategic culture and collective defence capacity. The Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 accelerated this trajectory, culminating in initiatives like the EU Strategic Compass, which aims to deepen cooperation and resilience by 2030.

Beyond military capacity, the EU actively engages in peacekeeping and conflict prevention globally. The European Peace Facility (EPF), launched in 2021, exemplifies this ambition by funding missions that stabilize fragile regions, help prevent conflict, and promote peace worldwide. Currently, thousands of EU personnel serve on peacekeeping missions across continents, projecting the Union’s commitment to security beyond its borders.

The EU, therefore, stands today not only as a unique economic union but as a peace project grounded in supranational governance, multilateral cooperation, and a shared commitment to stability. This legacy of turning conflict into cooperation is particularly relevant to Bosnia and Herzegovina, a country still shackled by Dayton’s fragile peace.

For Bosnia, EU integration offers more than economic gains—it is an invitation to join a system built to overcome ethnic divisions through the rule of law, democratic governance, and shared values. Designed to limit the power of strongmen, the European model provides a promising framework to tackle entrenched corruption, institutional paralysis, and nationalist politics that have long hindered Bosnia’s progress. I have seen it first hand. It works.

As EU leaders like former High Representative Christian Schmidt have argued, European integration offers Bosnia “the best—and perhaps the only—path towards sustainable peace and prosperity.” Yet this path demands more than symbolic gestures. It requires real reforms, political courage, and the willingness to break free from the constraints of Dayton’s outdated framework.

Remove the bad actor in Bosnia, Your Excellency. The time for appeasement is over. Let’s fix it and remove a future source of conflict now.

Cyprus: The Island That Froze

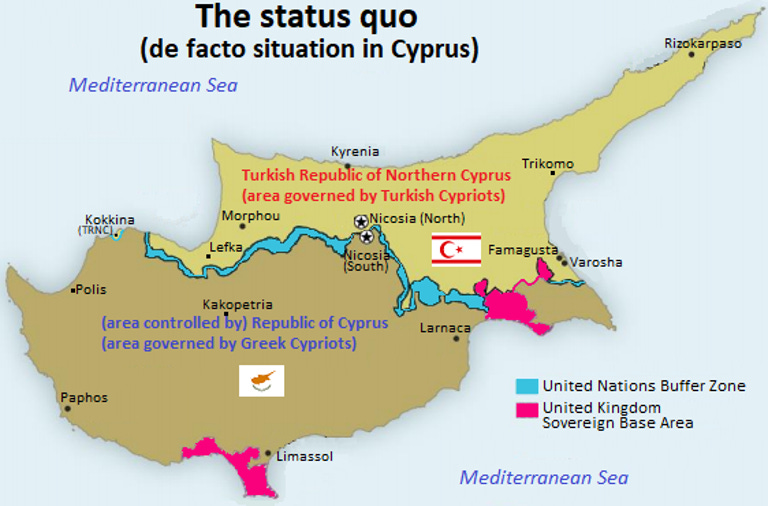

Cyprus is the Mediterranean’s unfinished proxy war—a divided island propped up by a permanent UN buffer zone and an uneasy peace that’s endured for over fifty years without resolving the root conflict. It stands, like Bosnia, as both a monument to international diplomacy and a warning about the paralysis of “frozen peace.”

Colonial Legacies and Political Fault Lines

Global attention first focused on Cyprus in 1955, when Greece-aligned Cypriots—roughly 80% of the population—launched an uprising against British colonial rule, demanding enosis (union with Greece). The minority Turkish Cypriot community supported taksim (partition between Greece and Turkey), stoking ethnic tensions.

To avoid civil war, Britain, Greece, and Turkey brokered a compromise: a newly independent Cyprus. But there was no referendum. On 19 February 1959, the inconvenient Zurich-London agreements were signed—by Makarios and Fazil Küçük—behind closed doors and without consulting the people — a huge mistake once more.

The constitution that followed established a precarious bi-communal republic: a Greek Cypriot president and Turkish Cypriot vice president, each armed with veto power; proportional representation; separatist municipalities. Yet, before long, fault lines cracked. Violence erupted in 1963, and the UN deployed its peacekeeping force (UNFICYP)—one of its oldest missions—to stem the bloodshed.

It looked like a mini-Dayton avant la lettre.

1974: Coup, Invasion, and Partition

Tensions escalated into rupture in July 1974. A Greek-backed coup in Nicosia aimed to subsume Cyprus into Greece. In response, Turkey invaded—claiming its right as a guarantor power under the 1960 treaties. Turkish troops swiftly occupied the northern third, displacing 160,000 Greek Cypriots and prompting a reverse exodus of 50,000 Turkish Cypriots.

Once bustling Famagusta became a ghost town. By August, the island was sharply divided. In 1983, the Turkish-occupied north declared itself the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC)—a state recognized only by Ankara and condemned by the UN Security Council. To this day, no other country acknowledges it.

Unfortunately, little progress was made throughout the rest of the 1980s, or during the 1990s – largely due to the intransigence of the late Turkish Cypriot leader, Rauf Denktash.

A Peace That Stabilizes Without Healing

The Green Line, stretching 180 kilometers across Cyprus and through Nicosia—the last divided capital in Europe—came to symbolize the frozen conflict. UN peacekeepers patrol it to this day, enforcing a peace that prevents war but deepens separation.

Like Bosnia, Cyprus has been the subject of endless rounds of international mediation—each raising hopes, only to fall short.

The turning point came in the early 2000s, when the Republic of Cyprus was set to join the European Union. Ankara, recognizing that an EU-member Nicosia would gain the power to veto Turkey’s own accession, backed a renewed UN effort to resolve the division. The result was the Annan Plan—a comprehensive proposal for reunification.

But the gamble failed. Greek Cypriot leader Tassos Papadopoulos urged rejection, believing that imminent EU membership would strengthen their negotiating position and yield a better deal later. In the April 2004 referendum, two-thirds of Turkish Cypriots voted in favour, but three-quarters of Greek Cypriots voted against. One week later, on 1 May 2004, a divided Cyprus entered the European Union.

In the years that followed the failed Annan Plan, multiple attempts were made to revive negotiations between the two sides. Yet for a host of political, strategic, and psychological reasons, none gained traction. A renewed sense of hope emerged in 2013, when the Greek Cypriots elected Nicos Anastasiades—a leader who had openly campaigned in favour of the Annan Plan. Two years later, the Turkish Cypriots followed suit by electing Mustafa Akıncı, a moderate and vocal advocate of reunification.

With Anastasiades and Akıncı at the helm, the UN-facilitated talks finally began to show real momentum. Broad consensus was reached across key areas: governance, territory, and property rights. By December 2016, the process advanced to a new stage, with the UN announcing a high-level international conference to tackle the most intractable issue—security guarantees.

The first round convened in Geneva in January 2017, but collapsed on the opening day. A second attempt followed in Crans-Montana six months later, where negotiators endured ten days of intensive dialogue. Yet despite initial optimism, no breakthrough emerged. The UN Secretary-General formally closed the Conference on Cyprus, and once again, the island slipped back into deadlock.

In the aftermath, scholar Van Coufoudakis offered a sober reflection on the impasse:

Hiding behind the rhetoric that only a comprehensive settlement will resolve these issues will only encourage the continuation of Turkey’s illegal conduct. The Cyprus problem was and remains one of illegal invasion, continued occupation, and documented violations of human rights and not an inter-communal problem to be resolved by a new constitution based on the affirmation of the violations that took place in and since 1974 in Cyprus. The UN has conveniently forgotten the consequences of the League of Nations rationalizations over Ethiopia in 1935 and Chamberlain’s folly in Munich in 1938. Accommodating aggressors only wets their appetite.

The Present Paradox

Today, the Republic of Cyprus stands as a functioning EU member state—wealthy, stable, and internationally recognized—while the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) survives largely on Turkish subsidies and political patronage.

Meanwhile, the once-militarized buffer zone has become a tourist attraction: in Nicosia, cafés and shops now hug the edges of checkpoints; tourists wander across for the day, passports stamped on one side but unrecognized on the other. Yet beneath this surface normalcy, the political division remains absolute.

The deeper fracture is psychological. Two generations have now grown up in separation, with no living memory of coexistence. While efforts at reconciliation persist—bi-communal initiatives, civil society dialogues, and cross-line projects—they unfold within a structure that has long ossified.

Like Bosnia, Cyprus is caught in a peace that prevents war but also thwarts true resolution. A conflict paused, not solved.

Four Strategic Paths Forward

1. Continue the UN-Facilitated Federal Talks

Despite decades of negotiation, support for reunification via a bizonal, bicommunal federation is waning. Recent polling suggests that many Greek Cypriots are wary—fearing institutional paralysis, disproportionate power-sharing, and a return to political deadlock.

2. Turkish Cypriot Statehood Ambitions

Formal recognition of the TRNC remains improbable. Few states are willing to endorse unilateral secession, especially when it contradicts UN resolutions and EU law. Recognition would trigger diplomatic backlash and likely economic sanctions from the European Union—a dead end in the current geopolitical climate.

3. Annexation by Turkey

Absorbing Northern Cyprus into the Turkish state would be a dramatic escalation—and a geopolitical earthquake. Though such a move may appeal to some hardliners in Ankara, it would prompt universal condemnation, kill off any remaining prospect of EU accession, and erect a permanent, militarized boundary at the EU’s southeastern frontier. For both Turkish and Greek Cypriots, annexation would mark the end of autonomy—and the beginning of something far more volatile.

4. A Flexible, Incremental Approach

Amid stalemate, a growing number of voices advocate a pragmatic alternative: a slow, deliberate process of mutual gestures. Turkish Cypriots could return select territory or properties; in exchange, they might gain limited access to international platforms, participation in cultural and sporting events, or an agreement on energy revenue sharing. These steps need not imply recognition of the TRNC but could serve as confidence-building measures toward either eventual reunification—or at the very least, a dignified coexistence.

Peace as a Process: Cyprus in 2025

Cyprus remains divided, but the peace process has not stalled—it has shifted into quieter, incremental steps of trust and cooperation.

In early 2025, the UN appointed María Angela Holguín as its new envoy to rebuild confidence through symbolic, low-stakes measures. A high-level summit in Geneva is planned, alongside proposals like new Green Line crossings, joint infrastructure projects, demining, and cemetery restorations—small but meaningful steps toward reconciliation.

On the ground, an EU- and UN-backed initiative is restoring 30 abandoned cemeteries, turning sites of grief into shared remembrance. Trust is being rebuilt one grave at a time. Green Line trade reached €16 million in 2023, with 7.1 million crossings. EU-funded programs support civil society and infrastructure, slowly reshaping coexistence without forcing premature political solutions.

Politics, however, remain deadlocked. Turkish Cypriot leader Ersin Tatar pushes for a two-state solution, while Greek Cypriots reject partition and Turkish military presence. Property disputes and deep-seated grievances continue to fuel tension.

Cyprus today illustrates the essay’s core message: peace is not a fixed moment but an ongoing movement—sometimes slow, sometimes stalled, but never fully abandoned. The real question is whether the will to pursue it endures.

A Mirror to Bosnia

The parallels are unmistakable. Like Bosnia, Cyprus lives under a power-sharing architecture drafted abroad. Like Bosnia, it relies on international oversight: peacekeepers in Cyprus, a High Representative in Sarajevo. And like Bosnia, it shows how a frozen peace—designed to stop war—can also stop transformation.

Both cases reveal a deeper European dilemma: one half of Cyprus is a full EU member; the other, a legal and diplomatic vacuum. Bosnia is promised EU membership, but structurally paralyzed. The continent finds itself managing peace, not building it.

Cyprus teaches us something crucial: the longer a provisional settlement lasts, the more permanent it can become. What began as a "temporary" partition in 1974 has now persisted for fifty years. For Bosnia, the warning is clear—today’s stopgap risks becoming tomorrow’s status quo.

Northern Ireland: From Walls of Division to the Good Friday Agreement

I now turn to my third and final example—one that, remarkably, ends in hope.

The story of Northern Ireland is not merely one of religious or political strife. It is, more powerfully, the story of a peace that was not declared but constructed—patiently, painfully, piece by piece.

For three decades, from the late 1960s through the late 1990s, Northern Ireland endured what became known as the Troubles: an era of bombings and assassinations, of riots, hunger strikes, and funerals that blurred one into the next. At its worst, Belfast was a city physically and emotionally scarred—divided by concrete walls and barbed wire, with neighborhoods split along sectarian lines: Catholic versus Protestant, nationalist versus unionist.

And yet, by 1998, the unthinkable had occurred. A peace agreement—the Good Friday Agreement—was signed. Not a ceasefire in name only, but a genuine and lasting framework for coexistence. In a world littered with failed negotiations and broken truces, Northern Ireland became one of the rare places where a peace process not only held but slowly transformed a society once trapped in the cycle of retaliation.

The Sources of Division

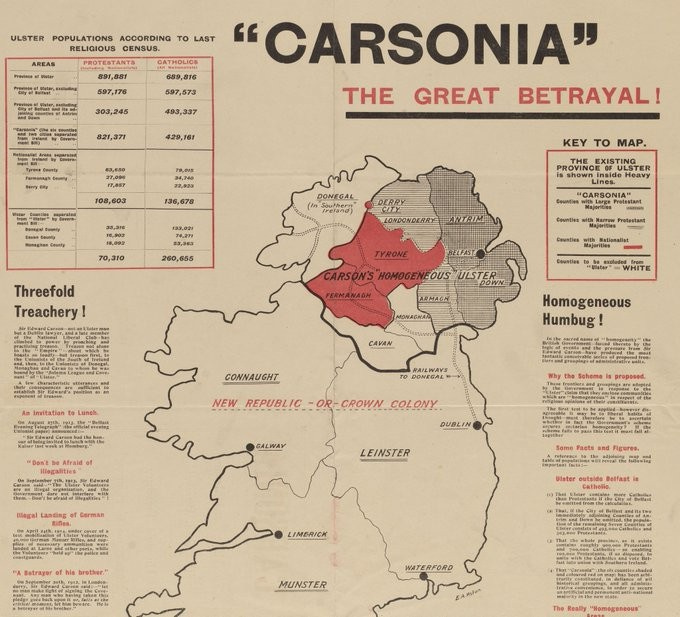

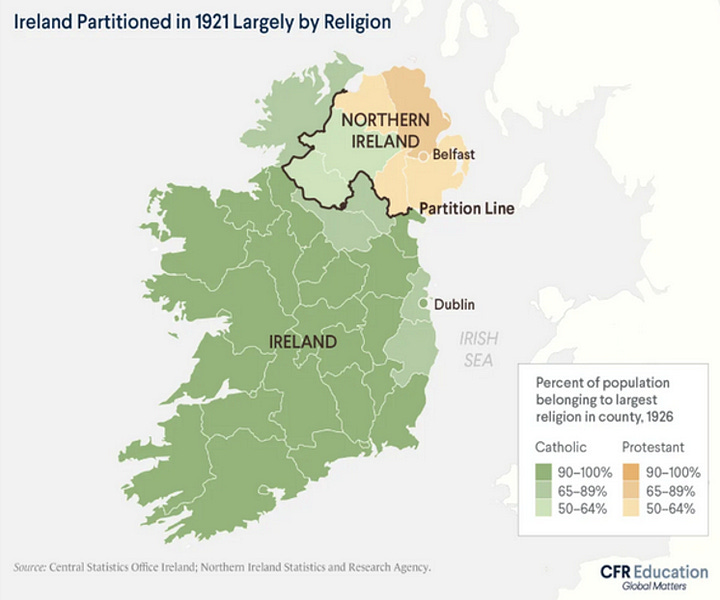

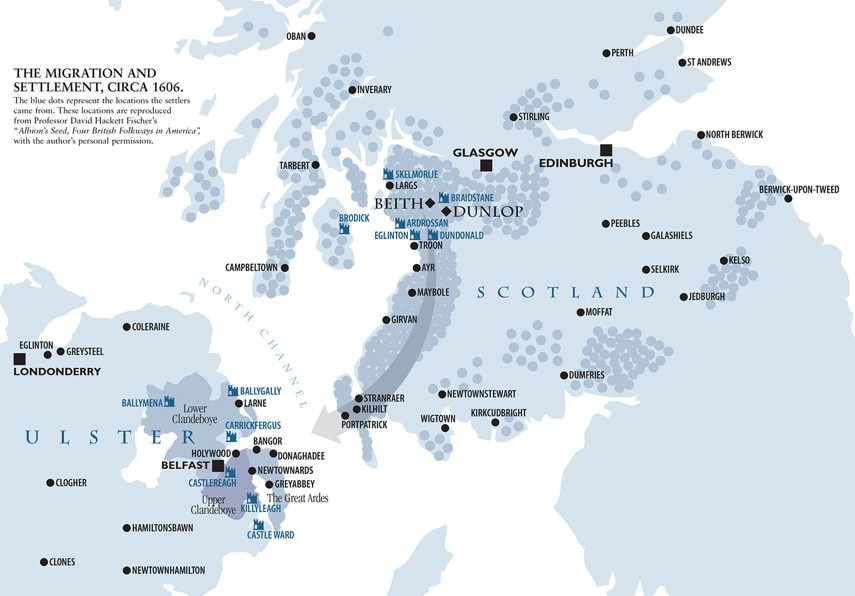

The roots of Northern Ireland’s conflict run deep—centuries deep. They trace back to the 17th-century Plantation of Ulster, when Protestant settlers from England and Scotland were granted land seized from the native Catholic Irish. This colonization didn’t just redraw the map—it planted a lasting demographic and religious divide that would shape Ulster’s politics for generations.

When Ireland gained independence from Britain in 1921, that historic divide solidified into partition. Six counties in the north—where Protestants held a majority—remained part of the United Kingdom. The south became the Irish Free State, later the Republic of Ireland. For Northern Protestants, partition safeguarded their British identity. For Northern Catholics, it marked a betrayal: they were left isolated in a state that did not represent them, cut off from the Irish nation they felt was rightfully theirs.

Northern Ireland became a Protestant-dominated polity. For decades, unionist governments at Stormont—the Northern Irish parliament—presided over a system of institutional discrimination. Housing, employment, and voting districts were all tilted to maintain Protestant power. Catholics were systematically marginalized—treated as second-class citizens in their own land.

Battle of the Bogside and Bloody Sunday

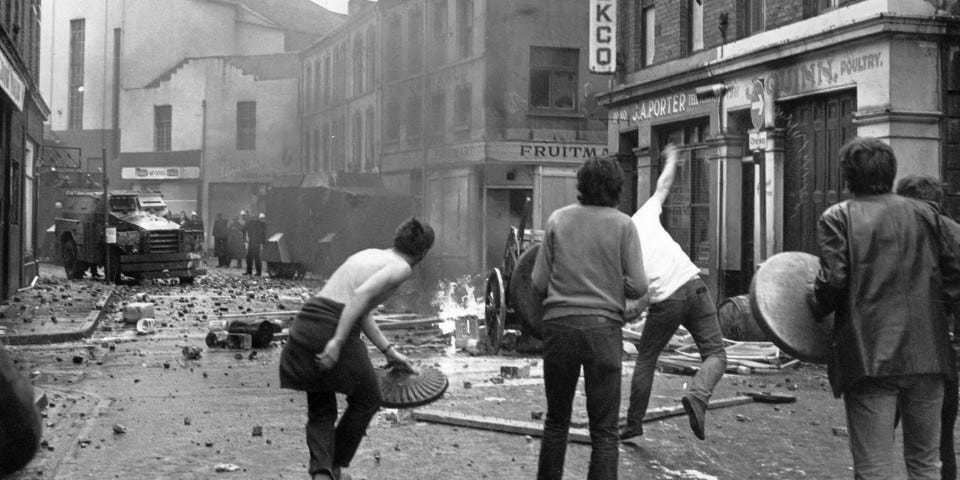

Many historians mark the true beginning of the Troubles with the events of August 1969, when a loyalist parade in Derry triggered days of violence that spiraled far beyond the city itself.

Across Northern Ireland, loyalist groups regularly staged parades to commemorate Protestant military victories dating back to the 17th century. In Derry, the local branch—the Apprentice Boys—planned one such parade for 12 August 1969, a patriotic display set to march directly past the Bogside, a predominantly Catholic and nationalist neighborhood.

For residents of the Bogside, the parade was not just provocative—it was incendiary. Fearing violence, they barricaded streets and stockpiled Molotov cocktails. As anticipated, tensions erupted. Clashes broke out between the Bogsiders, the Apprentice Boys, and the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC). The police response only inflamed the situation.

What followed became known as the Battle of the Bogside—three days of fierce rioting in Derry. But the worst devastation happened in Belfast, where loyalist mobs, assisted by the B-Specials (a reserve police force), attacked Catholic neighborhoods and burned more than 1,500 homes.

By 14 August, the Northern Ireland government had lost control. The overwhelmed prime minister appealed to the British government for help. British troops were deployed to restore order—marking the beginning of a military presence in Northern Ireland that would last nearly four decades.

Initially, Catholic nationalists welcomed the soldiers as potential protectors. But that changed quickly. The British Army soon introduced internment without trial, rounding up and imprisoning hundreds of suspected IRA members—many without sufficient evidence or due process. It radicalized entire communities overnight.

By the early 1970s, the violence had calcified into what many regarded as open war. The Irish Republican Army (IRA) relaunched its campaign to force British withdrawal and reunify Ireland. Loyalist paramilitaries like the Ulster Defence Association responded with their own terror campaigns, often targeting Catholic civilians. The British state, for its part, responded with force and surveillance, further fueling resentment.

Then came one of the darkest days of the conflict. On 30 January 1972, Catholic civil rights activists in Derry staged a peaceful march to protest internment. The British Army was deployed to contain the demonstration. What happened next shocked the world: troops opened fire, first with rubber bullets, then with live rounds. Thirteen unarmed protestors were killed on the spot. A fourteenth died later from his wounds. The massacre would come to be known as Bloody Sunday.

In the years that followed, Northern Ireland descended further into bloodshed. Car bombings, shootings, and sectarian attacks became tragically routine. Paramilitary groups on both sides—such as the Provisional IRA and the Ulster Volunteer Force—claimed hundreds of civilian lives, pushing communities even further apart.

Belfast and the Walls

Belfast became the crucible of Northern Ireland’s division. Entire neighborhoods were carved up along sectarian lines. As violence escalated, British authorities began constructing so-called peace walls—towering barriers of concrete, steel, barbed wire, and watchtowers—designed to physically separate Catholic and Protestant communities. By the 1980s, more than 100 such walls crisscrossed the city, turning Belfast into a patchwork of fortified enclaves.

An old friend of mine served as a British Army officer in Northern Ireland in the late 1980s and early 1990s. I remember him telling me how constrained the soldiers were by the rules of engagement: they could only return fire if they were shot at first. It sounds reasonable in theory, but in practice, it created a high-stakes, high-pressure environment. Every action—no matter how defensive—was subject to intense legal scrutiny. Even justified responses could result in formal investigations, or worse, prosecution. It was a kind of warfare unlike most others: fought not just on the streets, but in courts and inquiries long after the bullets had stopped flying.

Like the siege lines of Sarajevo or the buffer zone in Nicosia, Belfast’s walls became physical embodiments of political failure: visible, towering reminders that a society had split and could no longer find its way back together.

Thatcher and the Hard Years

The election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979 marked a sharp hardening of British policy toward Northern Ireland. To Thatcher, the IRA were not insurgents or political actors—they were simply criminals. “Crime is crime is crime; it is not political,” she declared.

In 1981, republican prisoners launched a hunger strike demanding recognition as political detainees. The strike electrified nationalist communities. Bobby Sands, a 27-year-old IRA member, was elected to the British Parliament while starving in prison. He and nine other strikers would die before the protest ended.

Thatcher’s unyielding stance deepened the conflict—but it also shifted its trajectory. For many republicans, the hunger strikes were proof that sacrifice could deliver political legitimacy. Sinn Féin, the IRA’s political wing, began seriously contesting elections, inaugurating what became known as the “ballot box and the Armalite” strategy: using both the vote and the gun to push for Irish unification.

It was a grim duality—violence and democracy running in parallel—but it signaled the start of a long, uneven transition from armed struggle to political negotiation.

Diplomacy and Shifting Ground

Even during the darkest years, seeds of diplomacy were quietly planted. In 1985, Margaret Thatcher and Irish Prime Minister Garret FitzGerald signed the Anglo-Irish Agreement. For the first time, the British government formally acknowledged the Republic of Ireland’s consultative role in Northern Ireland’s affairs.

Unionists were furious, viewing it as a betrayal by London. Nationalists, meanwhile, saw it as long-overdue recognition. Though modest in scope, the agreement opened vital channels of communication between Britain and Ireland—connections that would later prove essential.

In the 1990s, the diplomatic ground shifted more decisively. John Major, Thatcher’s successor, deepened cooperation with Irish Taoiseach Albert Reynolds. At the same time, across the Atlantic, newly elected U.S. President Bill Clinton broke with long-standing policy by granting Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams a visa in 1994.

The move infuriated London but sent a clear message: the United States was now willing to engage all sides—including republicans—in the pursuit of peace. Adams, once denounced as the public face of terrorism, was suddenly recast as a potential political partner.

Toward Peace

By the mid-1990s, exhaustion hung in the air. The violence, once fueled by passion and ideology, had lost its momentum. The IRA declared a ceasefire in 1994—broken and renewed again by 1997. Loyalist paramilitaries followed suit. Sinn Féin began emphasizing its political role, while unionist leaders like David Trimble came to accept a hard truth: if the bloodshed was to end, a deal was inevitable.

U.S. Senator George Mitchell, appointed by President Clinton, became the mediator—a calm, trusted presence amid deep mistrust. The European Union, working more quietly, invested heavily in cross-community projects that laid the groundwork for reconciliation. The stage was set for a grand bargain.nto cross-community projects. The stage was set for a grand bargain.

The Good Friday Agreement

On April 10, 1998, after marathon negotiations in Belfast, the Good Friday Agreement was signed. It was a triumph of careful language and painstaking balance. Among its key provisions:

A new Northern Ireland Assembly, based on power-sharing between unionists and nationalists. Neither community could govern without the other.

Cross-border institutions to foster cooperation between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

The British and Irish governments became joint guarantors of the agreement.

The “consent principle” was enshrined: Northern Ireland would remain part of the UK unless a majority chose otherwise.

Paramilitary groups committed to disarmament, and British military presence was scaled back.

Human rights and equality protections were formally embedded in law.

The deal was put to a vote. In referendums held north and south of the border, it was overwhelmingly endorsed: 71% in Northern Ireland, 94% in the Republic of Ireland. For once, peace had democratic legitimacy. It was not imposed—it was chosen.

After the Peace

The Good Friday Agreement transformed Northern Ireland. Belfast blossomed into a city of cafés, startups, and cultural revival. Tourists came to see the murals that once marked territories and enmities. The walls remained—but now more as monuments than front lines.

Still, peace has been fragile. The Northern Ireland Assembly has collapsed multiple times amid political deadlock. The legacy of trauma, mistrust, and sectarian division lingers. Brexit, too, threatened to unravel core compromises. But the Northern Ireland Protocol—a key part of the UK–EU withdrawal agreement—preserved the open border with the Republic. By keeping Northern Ireland in the EU single market for goods (unlike the rest of the UK), the Protocol upheld one of the central pillars of the peace process: the freedom to move seamlessly across the island.

It is this of creativity and adjustument that is certainly missing in Bosnia and Cyprus today.

The Lesson: Peace from Both the Top Down and the Ground Up

The Northern Ireland peace process stands as a powerful example of how deep transformation happens—not just through high-level agreements, but through sustained grassroots action.

Yes, political leadership was indispensable. Thatcher’s hardline stance inadvertently propelled Sinn Féin into politics; Gerry Adams, once sidelined, became a vital negotiator. David Trimble risked political ruin to push for compromise. Bill Clinton opened diplomatic doors, and George Mitchell’s steady mediation provided the scaffolding for agreement.

But just as crucial was what happened on the ground—in community halls, classrooms, and across neighborhood lines. From PEACE I to PEACE IV to PEACEPLUS, the EU backed over 15,000 reconciliation projects in just five years—spanning dialogue, school exchanges, and shared public spaces. Since the Good Friday Agreement, €2 billion has flowed into peacebuilding. Let me say it again: peacebuilding—not house building.

One Northern Irish civil servant, Quentin Crisp—author of The Naked Civil Servant—once quipped: “When I told the people there that I was an atheist, a woman in the audience stood up and said, ‘Yes, but is it the God of the Catholics or the God of the Protestants in whom you don’t believe?’” Let that sink in.

Let’s Get a Sense of Perspective

Peace in Northern Ireland wasn’t a single event; it was the invisible, relentless labor of thousands over decades. We can measure it.

Since the mid-1990s, EU-funded PEACE programmes supported over 22,500 local projects across Northern Ireland and the Irish border counties. One program alone—PEACE II—engaged nearly 870,000 participants. At the time, Northern Ireland’s population was only about 1.6 million. That’s more than half the country, touched by one initiative.

Let’s do the math. Assume conservatively that each of the 22,500 projects had just two core staff working two years each, at 1,000 hours per year (roughly 4 hours/day for 250 days). That’s 90 million hours of on-the-ground effort (22,500 × 2 × 1,000 × 2).

Add the civil service. With about 25,000 staff over the years, if just 10% of their workload touched peace delivery—grants, reports, coordination with Dublin, London, Brussels, Washington—that adds another 80 million hours (25,000 × 2,000 working hours × 10% × 16 years).

Now factor in civil society. Northern Ireland has one of the most active volunteer sectors in Europe. Surveys in the 2000s recorded tens of millions of hours volunteered annually. Even if just 5% was focused on reconciliation or community healing, over three decades that adds over 300 million hours of effort.

Altogether, that’s easily half a billion hours invested in peace—not counting the conversations, compromises, or quiet moments that never made it into reports.

And that’s the lesson: Peace in Northern Ireland wasn’t simply signed. It was worked into being—again and again—in town councils, church basements, classrooms, and government offices. That’s what “peace is a process” really means: Not a headline. A generational labor. Measured not in words, but in hours.

For Each Hour of Violence—Thousands of Peace Work

If you try to weigh the time it took to stop the killing against the time invested to keep it stopped, Northern Ireland’s balance sheet is lopsided in the best possible way.

Between 1969 and 1998, police recorded 36,923 shootings and 16,209 bombings—roughly 53,000 violent incidents in total. Even if we convert that crudely and conservatively into “hours of fighting” (treating each bomb or shooting as one hour of active violence, though most lasted only minutes), we’re looking at ~53,000 hours of conflict activity.

Now set that against the scale of peace: an estimated 500 million hours of peacebuilding, from civil servants, educators, volunteers, local activists, EU administrators, and community workers over the last three decades.

On that math, the exchange rate of history looks something like this:

For every single hour of recorded violence, Northern Ireland has invested between 1,700 and 3,400 hours of peace work.

And if you lean just slightly closer to reality—acknowledging that many violent incidents lasted less than an hour, or that most peace projects were longer and involved more people—the ratio climbs easily into the many-thousands-to-one.

The point isn’t false precision. It’s scale. The Troubles produced tens of thousands of violent spikes. But peace required millions of discrete actions: Writing grant bids. Booking rooms. Drafting legislation. Mediating neighborhood disputes. Running school exchanges. Auditing funds. Training facilitators. Revising curricula. Listening—again and again.

When translated into time, the truth is simple and sobering: Peace has taken thousands of hours for every single hour of violence—and it still does.

Secret Peacemakers

Peace needs more than top-down diplomacy and millions of hours of work. It needs bottom-up leadership—the kind that can’t be scripted or summoned by official decree.

In 1976, after three children were killed by a runaway car driven by an IRA member shot by British troops, two women stepped into the void. Betty Williams and Mairead Corrigan did something unthinkable at the height of the Troubles: they marched. Side by side with mothers, neighbors, and strangers—Catholic and Protestant alike—they walked into Belfast’s no man’s land, carrying a simple, defiant message: enough.

Barbed wire was pulled down. Silence gave way to conversation. Neighbors shook hands. Streets were reclaimed—not by force, but by will. Their movement, The Peace People, rallied tens of thousands. They didn’t care who held the gun—they wanted the killing to stop. For this, Williams and Corrigan received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1977. The movement would later lose momentum, but not its meaning: it proved that in the darkest hour, ordinary people can lead—and sometimes, they lead louder than governments or guns.

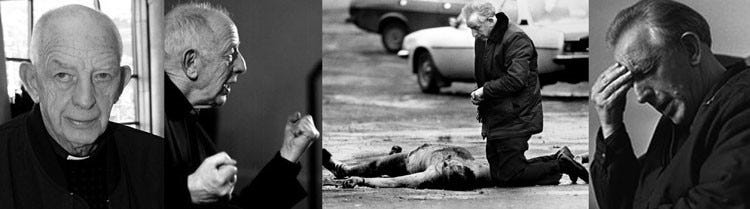

Another such figure was Father Alec Reid, a Redemptorist priest from Belfast who worked behind the scenes for more than 20 years to make the impossible thinkable. He quietly opened channels of dialogue between Sinn Féin’s Gerry Adams and SDLP leader John Hume—laying the human and political groundwork for what would later become the Good Friday Agreement. Reid’s principles—justice, consent, mutual respect—echoed years later in the terms of that peace. And the photo of him administering last rites to two murdered British soldiers in 1988 became one of the defining images of human dignity in the face of brutality.

Hume himself, though a political leader, embodied patience and moral clarity. For decades, he championed non-violence, European-style integration, and constitutional politics, even as he faced criticism for engaging with Sinn Féin. He shared the 1998 Nobel Peace Prize with David Trimble, the unionist leader who also risked everything to strike a deal.

But the deeper architecture of peace was built beyond politics. Thousands of teachers, clergy, youth workers, and community organizers laid the foundation for trust. Initiatives like the Corrymeela Community created safe spaces for dialogue. Women’s coalitions and cross-community groups sustained relationships long before political institutions could formalize them. These “ordinary giants” didn’t make headlines—but they made peace possible. They held the line when official talks stalled, and built the human infrastructure that held Northern Ireland together.

When Violence Becomes Profit

Peace may require half a billion hours of labor, but war—when entrenched in identity and conflict—demands almost no investment yet yields immense returns for a few.

Consider Hamas: multiple credible reports estimate that leaders like Ismail Haniyeh and Mousa Abu Marzouk are billionaires, each with fortunes ranging from $3 to $4 billion, amassed through misused aid, smuggling networks, and investments abroad. Meanwhile, ordinary Gazans—many displaced and impoverished—bear the brunt of conflict.

The situation is worsened when humanitarian institutions become compromised. According to IMPACT-se, over 10% of UNRWA principals and senior educators in Gaza are affiliated with Hamas or Islamic Jihad. These schools sometimes teach extremist narratives, glorifying martyrdom and erasing Israel from maps. The infiltration is not anecdotal—it is operational, using aid networks and educational platforms to perpetuate violence.

In this model, pain becomes capital, and war becomes a means of enrichment—through money, ideology, and power. In such settings, peace treaties can ring hollow unless they dismantle the systems profiting from conflict. Bosnia comes to mind too.

At the end of the day, it’s easy to play the victim, point fingers, or fall into simplistic blame. But it takes genuine courage, hard work, and a grounded moral framework to build a different path. Peace demands not just agreements, but the dismantling of structures that translate suffering into profit.

Conclusion: Peace Is a Process

Once treaties are signed, the real work of peace begins.

Peace isn’t declared; it’s cultivated. It must become a shared mentality—built brick by brick, person by person, community by community. Without broad civic engagement and visible symbols of trust—and without leaders brave enough to walk the political tightrope—peace remains fragile. Northern Ireland shows that lasting reconciliation requires both the wisdom of negotiators and the will of the people. It also demands a clean break from corruption and conflicted interests.

Peace is not a singular event, but a layered process—from negotiating tables to street corners, from foreign diplomacy to grassroots projects. Strong leadership can open the door to compromise, but it is citizens—through schools, youth programs, and quiet acts of cross-community courage—who lay the foundation for something that endures.

For Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cyprus, Kosovo, Moldova, and for Europe as a whole, peace will never be “done.” It must be tended—politically, socially, and psychologically. It must be renewed by each generation, not merely remembered by the last. Northern Ireland proves what’s possible. But it only happened through a peace mentality—powered by collective virtues, not just political signatures.

As Quentin Crisp once said: “If at first you don’t succeed, failure may be your style.” But peace, at its best, rewrites the script.

With warm regards,

Alexander Stahel

Appendix: Turkey — The Candidacy That Froze in Time

Turkey’s EU accession, once a beacon of hope, is now stalled indefinitely. Since applying in 1987 and gaining candidate status in 1999, the process promised to bridge East and West—but that bridge was never completed.

Key obstacles persist: Turkey’s refusal to recognize EU member Cyprus and its democratic backsliding under Erdoğan, marked by crackdowns on dissent and erosion of the rule of law. The EU has made clear these issues are non-negotiable.

No new negotiation chapters have opened since 2016. Accession talks are effectively dead, replaced by “recalibrated partnerships” focusing on limited cooperation. Erdoğan’s pivot eastward and threats to sever ties with the EU underscore the growing divide. Though opposition leaders pledge renewal, the structural gap remains wide.

Turkey’s stalled candidacy reminds us that EU membership demands shared values and reforms—not just strategic importance. Without these, the process grinds to a halt. Sometimes, one can’t help but miss the secular vision of Atatürk.

You have described a really good framework on what constitutes a lasting peace versus a fragile peace by outlining in details the examples of Bosnia, Cyprus, Northern Ireland, and the EU. I have taken many notes through out the series. It has really deepen my understanding for how these complicated geopolitical conflicts interplay with each other and what it takes to achieve a lasting peace. I have thoroughly enjoyed reading the entire series and well done for providing a well researched articles. Cheers.