Osisko Development: Unusual Geology is the Risk

When difficult geology meets excellent management, it is almost always the difficult geology that wins.

Mining veteran Sean Roosen’s message for the industry: “Shut up and drill”

Gentle Reminder

Before diving into Osisko Development, a brief note. The easiest way to extract value from this Substack is to revisit my earlier pieces on underground gold miners, namely Alamos Gold, Lundin Gold and K92 Mining.

They outline some technical foundations and investment principles that matter most in this sector. I won’t repeat those lessons here and in future posts. Instead, I build on them. A quick refresher will help frame the analysis that follows and make the nuances of this post far easier to absorb.

Mining Developers and the Lassonde Curve

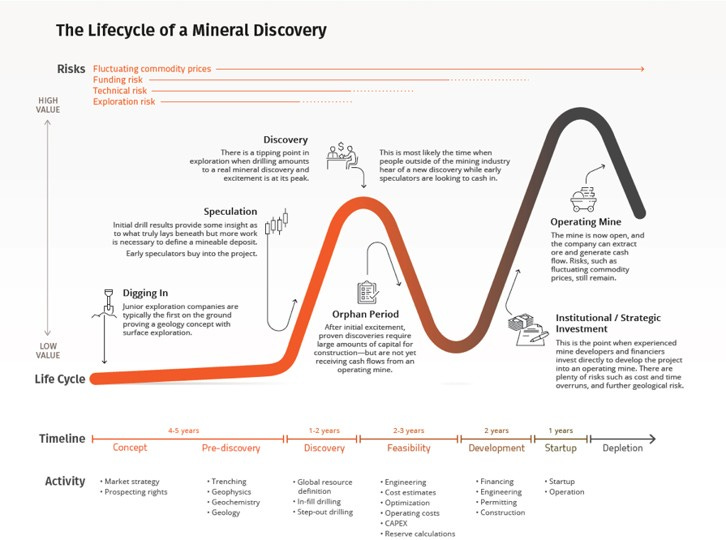

Before assessing Osisko Development, it is worth revisiting a framework that has guided my thinking for years: the Lassonde Curve, named after Franco-Nevada co-founder Pierre Lassonde.

The Curve is not a law of nature, but it is one of the most useful mental models for understanding how value is created and destroyed during the mining life cycle. It maps the major inflection points in a project’s journey and helps investors distinguish between geological uncertainty, permitting and funding risk, construction risk, operating risk and above-ground jurisdictional risk. Over time, it has helped me identify where genuine alpha in this sector tends to emerge.

The Curve follows a simple narrative arc. It begins with the concept phase, when a company acquires ground, conducts early mapping and sampling, and tries to raise capital on a geological idea. If the rocks respond, the project enters the discovery phase, where drilling defines the scale and quality of the mineralisation. This is often the moment of maximum excitement and maximum volatility, because the market is forced to update its priors in real time.

If a discovery holds together, the project moves into the feasibility phase, where engineers, metallurgists and financiers replace the geologists. Here, PEAs, PFSs and FSs translate drillholes into mine designs, capital budgets, operating cost estimates and economic models. The romance of discovery gives way to spreadsheets, trade-offs and discipline. A strong feasibility study can re-rate a project; a weak one can collapse it.

From there, the Curve descends into the development phase, the part of the cycle that destroys the most value. This is where permitting, funding, inflation, labour shortages and cost overruns collide with reality. Only once construction is complete does a project reach the start-up phase, where the mine produces its first metal and the market finally learns whether the geology, engineering and cost assumptions were accurate. By then, the risks are fewer, but so are the potential returns.

The Lassonde Curve does not tell you whether a specific project will succeed. It is not a substitute for technical and common sense due diligence. But it does remind us that the market consistently misprices risk as a project moves from imagination to execution, and that the sharpest opportunities, and the most painful losses, tend to cluster around the transition points. Understanding where a company sits on that curve is often half the investment decision.

And here is how Sean Roosen positions the company on the Lassonde curve. He basically pitches a re-rating, i.e. construction start to producing gold miner (development stage), along the lines of G Mining Ventures and Artemis Gold, two of the best gold companies in the sector (I will discuss both these companies in December). Is this realistic?

Ticking All the Development Boxes?

At first glance, Osisko Development appears to tick every box required to catch the next upward leg on the Lassonde Curve.

The company controls roughly 4.5Moz of resources at Cariboo in British Columbia, with a risked NAV at spot of about C$3.4bn. On a fully diluted share count of 377 million, assuming the 19.1 million warrants do not meet their strike, this implies a value of C$10.25 per share, or roughly 108% upside from its close on 30 November 2025.

The headline story seems attractive. Cariboo, the company’s flagship, is now fully permitted at the provincial level and fully financed as of Q3 2025. Construction should begin in 2026, with first gold at the end of 2027 and a ramp-up to 4,900tpd some time in H2 2028. The entire effort is led by Sean Roosen, one of mining’s few modern-day legends. For a gold developer in a Tier-1 jurisdiction, this combination of scale, permits, financing and elite leadership is rare.

Viewed against the broader development universe, Cariboo stands out. Rupert’s Ikkari is high quality but remains years from first gold and still sits in the permitting maze. Skeena’s Eskay Creek is not yet permitted but already sports a US$2.2bn valuation. Perpetua, heading toward a federal Record of Decision, is valued at US$2.5bn. Probe Gold’s Novador has just been taken out by Fresnillo. Snowline faces a long and uncertain permitting risk and infrastructure cost road in the Yukon. Coffee, now owned by Fuerte Metals, has major execution questions ahead. Seabridge and Novagold each require US$8bn+ and remain too large for the usual financing channels for now (think dilution). West African names like Montage Gold or Robex–Predictive are interesting but carry jurisdictional baggage and share overhang risk, if you studied it closely.

Note: we will discuss all the relevant names above over the coming weeks.

On that landscape, Cariboo can look irresistible. A permitted, financed, construction-ready Canadian gold project with multi-million-ounce scale and a household-name operator at the helm. For many portfolios, it feels like the project you “have” to own.

And Sean Roosen sells this vision masterfully. In one interview he even jokes that you can order pizza and McDonald’s from the mine site, proximity that most developers could only dream of. He is an outstanding communicator and, more importantly, an outstanding miner. None of that is in doubt.

But now we must turn to what really matters and what will drive the success or failure of this project far more than permits, infrastructure or charisma. This is where the narrative stops being all blue sky. The central issue, again, is geology.

Before walking through it in detail, listen carefully to Roosen himself. At Minute 7:15–7:45 of the interview, he says:

“And we know it’s there, but we didn’t do enough detailed drilling to define it. And we’ve averaged about 1.2 million ounces of overall resource for every kilometre that we’ve drilled over the 4.4 kilometres. So the next plan is, so we’ve got the main 2.2 million ounces. 2 million ounces is there, the measure indicate and inferred. That’s in and around. That is the next plan. The ‘at depth target’ is just to keep extending these vein corridors. At depth it is this orogenic system. Very, very predictable, very knowable.”

This is where the story becomes more complex—and where the technical realities matter much more than the marketing sheen.