Lundin Gold: A Geological Unicorn, Priced for Perfection

Fat panel, high grade, real optionality; patience required at 1.7× NAV

“Early on I learned that it takes as much time and effort to do a small project as a large one.” Adolf Lundin

Girlfriend, Not a Marriage

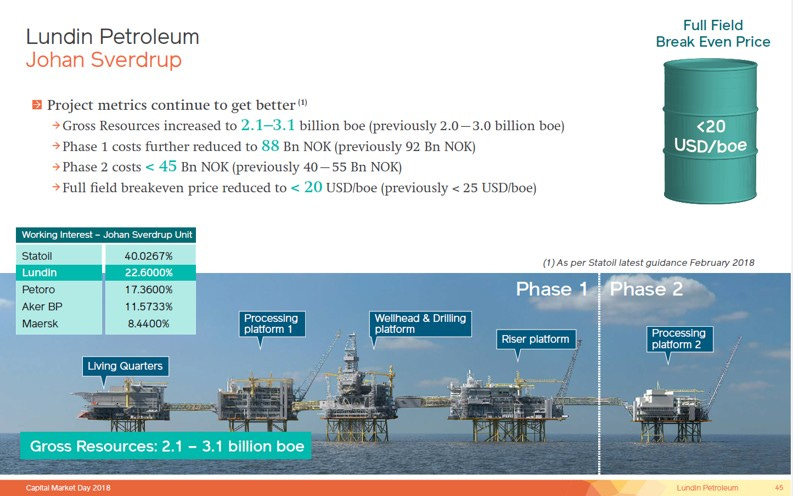

I first met Ron Hochstein at a classic speed-dating session—Berenberg, Zurich, 2018—when they pitched me Lundin Gold. I knew the Lundin dynasty from the oil patch. Lundin Petroleum rode Johan Sverdrup and was the best value for money on the Norwegian Continental Shelf besides Aker BP, by a country mile. But I wasn’t into gold miners; gold trades off real rates and I wasn’t exactly bullish on the metal.

Still, it was a Lundin outfit, so I burned 45 minutes crossing town—almost as big a waste of time as broker speed-dating. My mindset: maybe a girlfriend, not a marriage. Once the dog-and-pony show ended, I asked two things: how do you work with Lukas Lundin (mining side; Ian Lundin ran the oil side), and if you had a silver bullet, which competitor would you take out?

Ron was mid-construction and looked appropriately stressed. His answers: “two to three times a day,” and “Pretium.” Yes, you read that right. Lukas Lundin—who ran many operations, including Lundin Mining, Bluestone Resources (a gold development that was left for dead later), Filo & Josemaria (both copper explorations in Argentina which took off big later; no, they didn’t own NGEX back then)—called Ron multiple times a day for construction updates.

Anyway, Ron delivered on time and on budget. Or rather, the Gignac family did—with their mine-construction firm, G Mining Services. Today I know they’re the best construction team on the planet—mining hall-of-fame material. Back then, I had no clue. Remember the name; we’ll come back to them in this series.

The Lundin Gold stock, meanwhile, gyrated in 2018 like a pole dancer on an oil-slicked stage. Not much of a Lassonde Curve to admire. Only in June 2019 did it finally move—from C$5.10 to C$8. Partly because it was nearing commercial production (declared in February 2020), but also because gold did a 20% shuffle from US$1,250 to US$1,500.

Miners were hated across the board—precious, base, anything metallic. Why go asset-heavy when you could own Google’s asset-light recipe? When my “girlfriend” finally perked up, I happily passed her to the next suitor at C$8. Early 2020, the stock overshot gold as commercial production was announced for a few weeks, then cratered back to C$5 during Covid when Q2 2020 production went dark.

From there Ron delivered—or overdelivered—quarter after quarter, and yet the stock merely tracked gold for roughly 10 straight quarters, just with more whiplash. So no, you’re not gonna win a market-neutral set-up as a hedgy in metals. By July 2022 it was back under C$8, broadly in line with the metal. So much for the “leveraged play” in a quality name; it traded more like a guaranteed put on a slippery earnings print. That 2018 meeting taught me more about gold mining than I realized—less romance, more cash flow; keep the relationship casual until the geology proves it wants a ring.

And for the record, I owned Pretium too. That was the real stomach acid. Why, you ask? Try my last post on Alamos. The answer’s there—assuming you can read. Hint: geology. No, Pretium’s problem wasn’t grade; it was nuggety, discontinuous geology—bonanza pockets stitched through blank rock, the textbook nugget effect. Wall Street hated it. Bottom line: nature and quarterly reporting are rarely a match made in heaven.

Fun fact:

Lundin Petroleum, born in 2001, discovered Johan Sverdrup. Yes, Statoil showed up later, but Lundin made the first strike in 2010 on Avaldsnes with well 16/2-6—later recognized as part of Johan Sverdrup.

Why does that matter? Because Johan Sverdrup is, by far, the largest conventional offshore field in the North Sea today (Ekofisk/Statfjord were bigger in their days): 2.7 billion barrels of recoverable reserves and a plateau capacity up to 755,000bpd—roughly a third of Norway’s current oil production. Let that sink in. And yes, just like the best deposits, Johan Sverdrup only got bigger as the drill bit did the talking.

After the merge with AkerBP in June 2022, their Working Interest in the field is 31.57%. Nemesia, the primary investment vehicle of the family, holds 14.38% of AkerBP as per Bloomberg at the time of this writing, worth US$2.2 billion.

Better Lucky AND Brilliant: The Fiscal Turn That Made Fruta del Norte

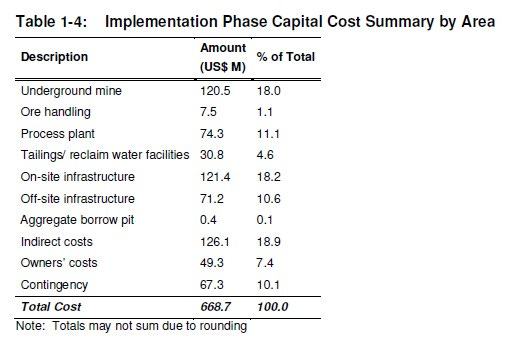

Lukas Lundin bought Fruta del Norte (FDN) from Kinross in December 2014 for US$240m—US$150m in cash and US$90m in Fortress common shares (today’s Lundin Gold).

At the time it was one of the largest, highest-grade undeveloped gold projects on the planet: 36 mining concessions over 64,300 hectares in southeast Ecuador, 80 km east of Loja. In Kinross’s book, FDN carried 7.2Moz M&I and 2.5Moz inferred. To prove up the system, Aurelian—the original discoverer—and later Kinross drilled at least 141,000 exploration metres from 2006 to 2012 in proper jungle conditions. In today’s drilling-cost terms, that’s roughly US$50m before technical work.

Kinross walked in 2013 after failing to agree key fiscal and legal terms with Ecuador, including a punitive windfall-profit construct of 70%. The government also wouldn’t grant the stability Kinross wanted. Mining is long term. Hence, good mine operators want a legally binding standstill agreement that is enforceable under international arbitration. Consequently, Kinross took a US$720m write-off (mostly non-cash), including US$20m in severance and closure, and treated FDN as discontinued. Despite sabre-rattling over the licence timeline, Kinross ultimately sold to the Lundin group.

For perspective, in 2014 Kinross produced 2.7Moz GEO (gold equivalent) and carried 34.4Moz reserves, 23Moz M&I and 4Moz inferred, with a US$3.2bn market cap. In other words, the market valued all of Kinross’s resource at US$52/oz with gold at US$1,266/oz. Kinross sold FDN for US$25/oz of resource. Today, markets value 15Moz of FDN resources at north of US$1,000/oz—forty times that. Not bad.

Did Kinross blow it? Not ex-ante. In 2013–2014, Ecuador’s regime under Rafael Correa (notably the 70% WPT) made FDN uneconomic for a major at US$1,300/oz. The mine was in the middle of nowhere and required power lines, roads and plenty of upfront capital. The US$240m exit was rational. One could even argue it was a good price, likely replacing most of Kinross’ cash cost. Who knows.

What we do know is that Latin America had the usual above-ground noise around that time. On 6 February 2016, The Economist was tallying social-licence conflicts across the region. Chile’s Supreme Court suspended Pascua-Lama; Colombia’s courts blocked Mandé Norte. Latin America has the metals endowment across the periodic table, but politics were (and are) a contact sport. And that is why Ecuador remained a mining minow. It had a mere 60 mines operating in 2015 and registered 7 conflicts in the piece. That is 12%—“Lodes of conflict,” as the title of the graph correctly reads.

Only after Lenín Moreno took office in 2017 did Ecuador finally grow up on mining policy—the 2018 reform killed the 70% Windfall-Profits Tax (WPT) for mining and made the regime investable. But when Lukas bought in December 2014, the “reforms” (Decree 475 and a grab bag of incentives) were lipstick on a pig; the 70% WPT still hung over the model. For a portfolio major, FDN screened poorly. And Quito wasn’t offering squatters’ rights: work it or risk the licence. You can’t have your cake and eat it too. Lukas was a risk taker in the Lundin family sense. Adolf is quoted to have said, “no risk no glory”. It lived on in his most capable sons.

By 2016, Lundin announced the adult thing—paper first, rocks second. Call it proper risk management. The Exploitation Agreement locked the project’s fiscal rules and clarified how the WPT would work: it would apply only when the metal price exceeded a stipulated contract “base price,” and only after FDN had recouped its cumulative investment (the Government even floated “payback + four years” during the legislative clean-up). In plain English: the 70% take hit just the price-above-base slice, not every dollar of profit, and not until the mine had paid itself back. The contract also included a US$65m advance royalty—unusual for most mining jurisdictions, but part of the bargain to get bankable certainty for a worldclass deposit.

The Investment Protection Agreement signed later in 2016 layered legal and tax stability on top: a fixed 22% income-tax rate for FDN, ISD remittance-tax relief on debt service, and most-favoured-investor style protections. But none of that repealed the WPT. It just made the playing field knowable while the politics caught up. The actual repeal of the mining WPT arrived in 2018 under Moreno’s Ley de Fomento Productivo. That’s when the windfall tax finally left the stack. That was the game changer. And that was lucky.

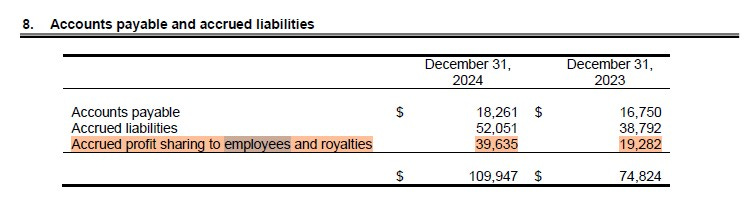

Today, Lundin Gold still pays plenty of taxes. If you own the stock, study the fiscal take as closely as grade and capex—it defines intrinsic value. Ecuador mandates a 15% profit share on pre-tax profits in mining: 3% to employees, 12% to the State. It shows up as 3% in operating costs and the 12% in the tax line.

On headcount, Lundin doesn’t list employees in the AR, but 2023 sustainability materials note 1,907 employees (local press pegs 2024 in the same ballpark). That’s a lot of paycheques tied to one mine—a real, tangible resilience mechanism in a country-risk discussion. Our calculation suggests FDN will pay out US$334,000 per employee, assuming a US$4,000 price deck, ceteris paribus.

FDN’s operator, Aurelian Ecuador, pays a fixed 22% corporate income-tax rate (CIT) for the life of the mine under the IPA, even though Ecuador’s headline rate rose to 25% in 2018. So that is good news. It shows some fiscal stability. It’s the little things that matter in judging country risk. Also, Profit Shares are deductable for the purpose of CIT. Sensible.

FDN obtained relief on debt service in the so-called Impuesto a la Salida de Divisas (ISD)—Ecuador’s tax on the exit of foreign currency. Dividends can qualify for ISD exemptions subject to the usual conditions, which we assume too. As social influencer and presidential candidate Gloria Álvarez in Guatemala explains: Latin America knows 50 shades of socialism. Finally, under the Canada–Ecuador treaty, dividends to Lundin Gold carry 5% withholding (treaty conditions apply); without treaty relief, Ecuador’s domestic rule is 10%.

In our intrinsic value work we thus model the stack as 15% profit share + 22% income tax + 5% dividend WHT, with profit share deductible before CIT and dividends paid after tax, the effective take lands below 42%. Not great, but certainly more competitive than many African regimes that layer equity carries up to 15% on top of royalty and income taxes.

In all, Lukas had timing and spine. Better lucky than brave, sure—but they were both. You couldn’t guarantee the political turn in 2017–2018; you could position for it. He sure did. But let’s be frank: the FS 2016—before the turn—suggested US$669m upfront capital to put the mine to work. The gold price in 2016 and 2017 averaged more or less US$1,250.

If we were to apply that price deck in our model with a 70% WPT, FDN would have had a hard time returning its invested capital—we mean ever. Even with the capital-recovery protection agreed in 2016, it still would have struggled to pay dividends later at a US$1,250 gold deck. Water under the bridge.

The IPA, combined with the 2018 repeal of the mining WPT under Moreno, made greenlighting FDN a no-brainer. Without both, Lukas might have walked—just as Jack Lundin (one of the two active superstar sons now running the mining side of the Lundin empire) did with Bluestone Resources in Guatemala in 2022. Adam is the other. Harry and William—also Lukas’s sons—are active on the energy side of the group. We’ll leave other family details aside; this story is about FDN.

Fun fact:

Blustone’s Cerro Blanco failed for a cocktail of reasons. The orebody basically sits under a hot-water volcano. During early underground development, massive inflows of near-boiling water made it unworkable, forcing then-CEO Jack Lundin to pivot in 2022 from an underground plan to an open-pit concept—after roughly US$120 million had already been sunk.

At the same time, Guatemala was sliding into an anti-mining phase, echoing Ecuador years earlier. The government suspended multiple licenses (2017–2019) citing “lack of prior indigenous consultation.” By 2022, NGOs had organized transnationally against Cerro Blanco, branding it a threat to Lake Izabal and cross-border water quality (think Loma de la Lata/Loma Larga-style controversy). The open-pit pivot—which implied large-scale dewatering and new waste storage—triggered a fresh EIA under tougher standards; the Ministry rejected the first filing in 2023. The project stalled and is now officially on hold, but dead in reality.

Moral: mining is hard—even for the best.

The lesson: if you invest long-duration in LatAm resources, you study politics, social issues and taxes like an operator and do not rely on management slide shows. The amplitude of change dwarfs North America, Australia, and Europe—despite the fashionable takes that “our” above-ground risk is just as bad.

Among us girls: it isn’t—except, of course, in the UK, with its so-called Energy Profits Levy (EPL), the local windfall tax that’s been kneecapping the North Sea’s best operators since the post-Russia gas shock in 2022–2023.

Fruta del Norte — The Geological Unicorn

Those of you who’ve followed me on X know the drill: resource investing starts with the deposit (in metals) or the reservoir (in oil and gas). A gift of nature can offset a lot of above-ground pain and price volatility. It’s the insurance policy for corporate survival—especially when it takes real technical skill to lift and sits out of easy reach of bureaucrats and “rebels.” Think offshore Nigeria in oil terms. Same playbook.

So let’s look at what Fruta del Norte actually is. Before the jargon, apply common sense. The ideal underground gold deposit looks like this.

Continuity. The ore body sits at moderate depth and runs laterally—a panel, not a pinprick; a football, not a fishing line. You drive in, not down a thousand-meter shaft. Minimal waste development. A short, straight road to ore. The grade shell barely pinches over mineable distances. Lower risk, lower cost, fewer surprises when it’s time to hit the quarter for Wall Street.

Width and depth. You want a thick, consistent block—again, football not spaghetti. Not stringy lenses disappearing at depth, not broken shoots you can’t find when you need them. Call it 100–150 meters true thickness, at serious grade, near enough to surface that physics and diesel are on your side.

Rock competence. You want competent host rock that doesn’t fall apart, so you can run big stopes without diluting grade. In the plant, you want metallurgy that cooperates—gold that separates cleanly enough to deliver high recoveries, without throwing the periodic table at it. Doré over alchemy; if you must make concentrate, fine, but don’t make it the only route to pay dirt.

That’s the dream. Continuity, simple geometry, competent rock. Simple!

A quick fun fact:

Gold is scarce but promiscuous—showing up in all kinds of rocks and settings. Nature turns the chaos into two money-makers: lode deposits (primary, in place) and placer deposits (secondary, where weathering and gravity sifted dust, flakes, grains, and nuggets over geologic time). That’s why some folks still strike it rich with a shovel while others need a decline, a mill, and a risk committee.

It’s a super-tricky metal, hosted in countless settings—and why, per kilogram, nothing gets close to gold’s price tag at US$139,000/kg while nickel sits at US$15/kg, copper at US$10/kg, and zinc at US$3.15/kg. P.S. whose bright idea was it to quote it in ounces? Absolute nightmare.

Now, let’s park the daydream and look at this ore body.

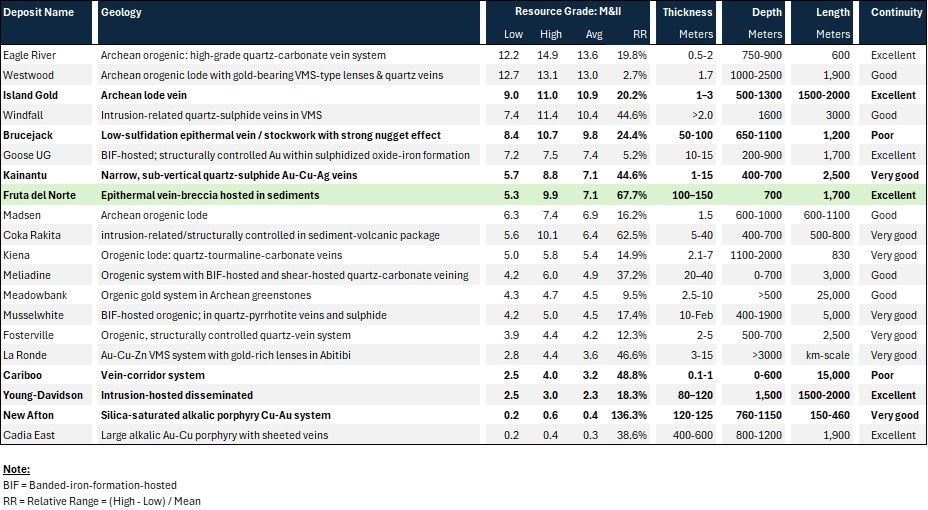

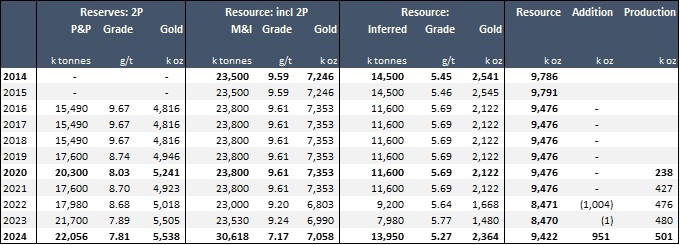

Fruta del Norte is an epithermal vein-breccia hosted in sediments. Now, I have no idea what that really means - geologically speaking. But in my resource table below you’ll notice three things that pop immediately if you’ve looked at enough mines. None of it takes a geology degree to comprehend, just commen sense and basic math.

First, grade: M&I averages in the 7g/t neighborhood with reserves around 7.8g/t—serious rock even in underground land. Second, scale: the ore zone is 100–150 meters thick, runs roughly 1,700 meters along strike, and sits around 700 meters below surface. Very special. Third, continuity: it’s a single, laterally continuous panel. That’s “rare earth” material.

The geometry makes the mining plan sing. A true thickness of 100–150 meters means big, mechanized stopes—exceptional at these grades. Access is by side portal and decline; you’re not hoisting from a kilometer down. It’s “drive to the face, mine, turn, drive home”—far simpler than the contortions at Island Gold or Young-Davidson.

Don’t get me wrong: Alamos turned both into industrial beauties. My point is that Fruta del Norte asks for less tech and fewer brain cells to deliver. It’s the kind of asset Buffett wants—a wide moat that even an idiot can run, because one day an idiot may will.

On the plant side, the company reports dilution around 8% and 88% gold recovery. That’s fine—room to optimize, but already very profitable rock. Metallurgy isn’t trivial here; FDN produces a mix of doré and concentrate, and the team keeps nudging recoveries upward. If they crack another couple of points consistently, so much the better—but let’s not get greedy now when geology is doing this much heavy lifting.

Geology Lesson: Now, please study the table again. Like the resource-development table in my Alamos write-up, it will teach you more than hours of mining-company financials. Why? Because most underground mines force a trade-off: you can have grade, or you can have width, or you can have continuity—but rarely all three. Island Gold is high-grade but narrow. Young-Davidson is wide but low-grade. Brucejack is rich but erratic. Kainantu is agile but vein-by-vein. Fruta del Norte alone delivers all three: a high-grade, thick, laterally continuous orebody—the kind of geometry explorers dream of but are highly unlikely to ever find in a career.

Fruta del Norte is the rarest thing in mining: size and obedience. Continuity, thickness, access, grade—four aces in one hand—translating straight into low costs and long duration. She’s a Latino beauty, but without the usual high-maintenance supermodel drama. Look at her. It’s screaming “buy.” Meanwhile 99% of Wall Street can’t read a long-section. A geological unicorn, hiding in plain sight.

If Escondida is the type example for open-pit copper, FDN is the underground gold analogue—an ore body that just gets the big things right. Per kilometer of strike, it’s one of the densest gold endowments per kilometer on the planet. A block of money lying flat at 700 meters, waiting to be mined for the next 20 years—methodically, predictably, without endless technical headaches. The proverbial gift of nature.

Which is why Lukas Lundin didn’t need a séance in December 2014. He’d looked at hundreds of deposits across metals. When a world-class geometry shows up at a price with a pathway to bankable contracts, you take the risk. Pros do.

And you don’t need to cosplay as a geologist to see it. Spend a few hours with technical reports, stare at the long-section, compare vein systems and thickness columns across peers, and let common sense do the work. Mining has so many comps it’s practically a stock picker’s playground. The edge isn’t in sounding smart; it’s in seeing the obvious—continuity, geometry, competence—and then waiting while the cash flow tells the story. Looking at geology and knowing who the real operators are is the legal version of front-running Wall Street.

If It Clicked, Click Share

I truly hope, over time, you realize that my way of explaining complicated matters simply is something you won’t easily find anywhere else—if at all in the resource industry. And it took years to get here.

Not even Lundin Gold—very good at knowledge translation—lays out the above comp table this simple and startling, one that lets a generalist recognize a geological unicorn at a glance. Instead, the industry is astonishingly hostile to generalists: complicated, technical, unapproachable. Zero knowledge translation. No wonder the sector struggles to attract retail.

My message: this Substack is unique, and I truly hope you’ll help me spread the word so others can see what isn’t hard to understand. If this is the analysis you wanted but couldn’t find, please help the next reader find it so that we can scale and justify the time and work it takes to delivering such inside to you.

Land Optionality: Let the Drilling Begin

Does the Latina supermodel have geological upside? I don’t know. Nor can we know. It’s a known unknown, in the words of former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. But there are a couple of things we can say.

Let’s start with the country. Ecuador—LatAm drama like the rest of the EM pack—did its best to stay poor by shutting the mining cadastre in 2018 over “irregularities in the concession system,” whatever that meant. Code for corruption, in all likelihood. It reopened in June 2025, finally launching new concessions after seven years to attract projects and curb illegal operations. Dahh.

Between 2018 and 2025, Ecuador didn’t outlaw drill rigs at FDN, but it starved exploration with policy, permitting gridlock, and uncertainty. Closing the cadastre froze fresh ground and slowed anything beyond the mine’s immediate footprint. Add the 2020 COVID stoppage and, later, court fights over new environmental-consultation rules (Decree 754 was provisionally suspended in 2023), and you had a national case of hurry up and wait.

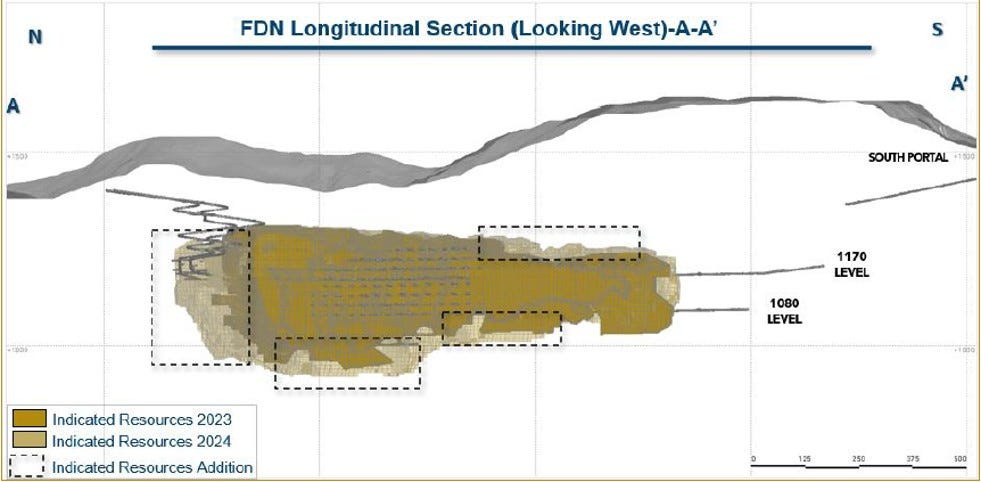

The rational choice for Lukas Lundin and Ron Hochstein was to build the mine first, chase ounces later, which is exactly why the resource history reads like a flatline with barely a pulse: tiny additions, depletion marching on, and not much movement until the drills came back in earnest in 2022/23, with real replacement finally in 2024. In fact, Lundin Gold didn’t even bother to report annual reserve reports for 5 years straight.

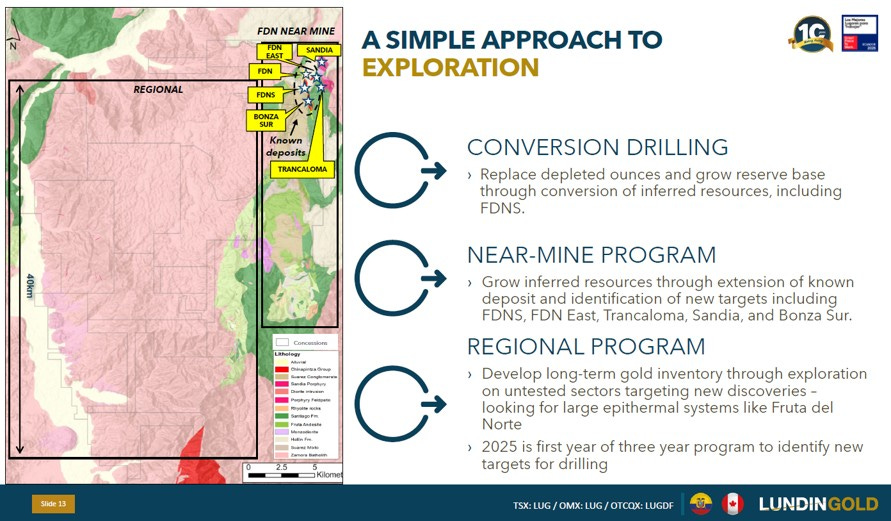

Once the mine was running and access improved, Lundin rolled out its largest district drill push since 2007—first near-mine, then regional. By 2021–2022 they were back on pads around the Suárez Basin, a 38km² pull-apart that hosts FDN and—crucially—looks big enough to host siblings. The run of news that followed (near-mine hits in 2022–2023, then a full district program) reads like a company taking the restrictor plate off. See for yourself.

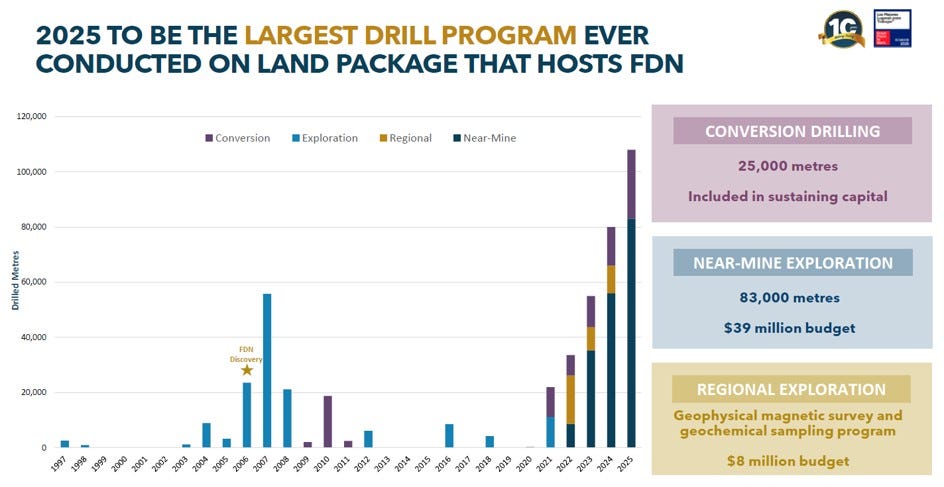

Can the company deliver on this 2025 ambition? Absolutely. Lundin is running 16–17 rigs in 2025, which is massive. At that fleet size, you need only 16–18 meters per rig per day to hit 108,000 meters—well within normal productivity, especially with a mixed fleet (surface + underground). The implied 8 meters per crew per day (two crews per rig) is conservative for diamond coring, leaving buffer for weather, maintenance, or pad moves. Ron and team will deliver—unlike the many junior lifestyle outfits without funding. Hunt elephants, not mice. It pays over time.

It gets better. Listening to Lundin Gold’s Investor Day 2024, studying their approach, and thinking about the industrial probability I get good karma in a probabilistic ballgame. They have a team of 20 geoscientists underpinned by a successful operating model. And much of it is new. VP Exploration Andrey Oliveira joined in March 2022. Since then, he’s hired 18 new geologists (ten women from communities around FDN).

Under his leadership, the company is focusing on near-mine exploration within a system that is open south, west, east, and at depth, plus a regional program—what I’d call a real exploration culture run by people who’ve actually seen this epithermal style before. Best of all, Andrey seems to embrace AI and big-data tools. Tech should let exploration make quantum-leap gains when applied with discipline.

Do I know what that will ultimately yield? No. Known unknown. But here’s a known known: Andrey’s team will likely turn over every single rock on 63,000 hectares of highly prospective epithermal ground—meter by meter, systematically, with no budget constraint and a tech stack unprecedented in Ecuador’s exploration history. That’s real horsepower. Name me a junior that can match it and fund it without equity dilution. There isn’t one.

Here, you get real exploration by pros—in proven geology, with a unicorn already on site, an operating mine ready to absorb any discovery (speed matters), and a rock-solid social contract on top. Keep that in mind when you’re pitched junior stories with nothing but glossy slides, a Lassonde-curve cameo, and “100x” typos. That’s not investing; that’s roulette—most of it noise dressed up as geology.

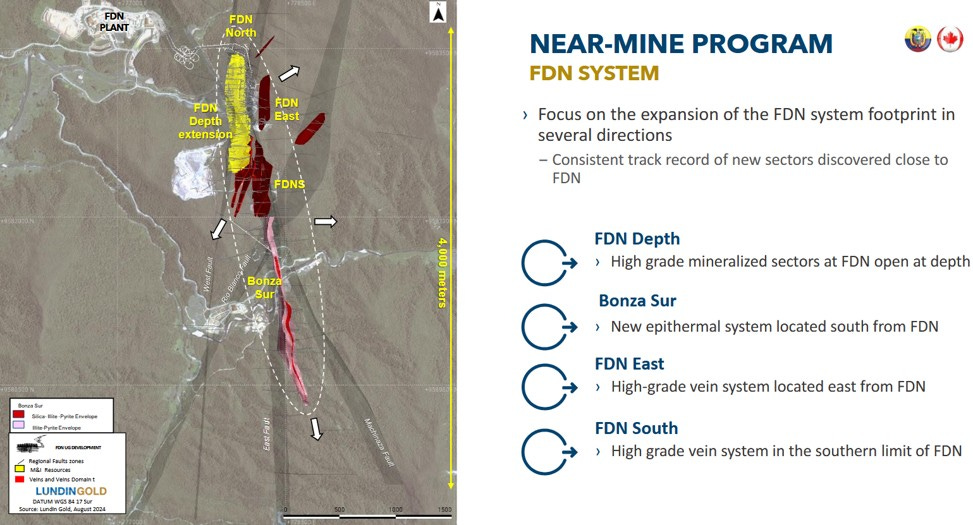

Here, the drilling is already paying off. Bonza Sur, one kilometer south of the FDN portal, started as a humble soil anomaly and is now a new gold deposit. The mineral envelope starts at surface, runs more than 1.8km along strike, is about 100 metres wide, and extends to at least 500 metres depth in drilling. That’s not a scout blip; that’s scale with geometry.

Lundin Gold is guiding to a maiden resource in H2-2025 and had one rigs chewing on it in Q2 2025. 11 surface rigs were drilling, with four of them at Trancaloma (east to FDN), one at Sandia (north east to FDN), one below FDN depth, one at FDN East, one at Bonza Sur, and three testing new sectors. Whatever they find inside the above white-dotted perimeter converts, by design, to high-margin cash flow—no fresh permits, no new mine build, no strings attached. Call it 1:1 conversion when its slot comes up in the mine schedule. Sexy.

Meanwhile, the regional map remains gigantic. Lukas acquired 64,300 hectares—roughly half the size of the Canton of Zürich with its 1.6 million inhabitants. It’s huge. There’s hardly a soul on it, and the land package has never been systematically explored. So yes, you can be cautiously optimistic that where one supermodel hid, a few mini-models may be waiting their turn. A dream come true for dreamers.

When FDN’s VP Exploration Andrey Oliveira says “epithermal systems are never alone,” he isn’t speaking figuratively. The geological corridor already hosts other mines and projects—Mirador (copper), Warintza (copper), and several prospects. The best mental model might be this: the Carlin Trend began with one orebody in 1961; today it’s a 90-million-ounce hydrothermal city. Pierre Lassonde understood the power of that optionality when he scraped together US$2 million to buy the royalty—every dollar he had.

Epithermal systems come in clusters, and if the geology stays preserved—as it has under the sedimentary cap at FDN for 150 million years—each new vein corridor can extend mine life by decades. I don’t need to and couldn’t lecture you for one minute on the petrology; I just need the history: that’s what nature did. What we’re watching in southern Ecuador could be the early chapters of a modern Carlin-style evolution, written in epithermal script rather than carbonate. With budget, brains, and tech, Andrey’s team is likely to find more gold, copper, silver, and friends. But let’s not outrun the drill bit—or mother nature.

Have we valued any exploration upside yet? No. I’m not going to model fences and micro-structures off a handful of holes, and unless results cluster, regional targets won’t become economic. Our model, however, uses ALL 9.4Moz of resources and risks none—chance of success set to 100% for the in-resource case.

Sell-side analysts typically value reserves in full, then apply a risk factor to measured and indicated, and often assign zero to inferred. They have their reasons, but most are intellectually flimsy and mainly designed to avoid embarrassment when the market is watching. Intrinsic value in resources has to be situational. But resources come in countless configurations: sometimes the extra ounces aren’t worth the paper their block model is printed on; sometimes they’re worth every ounce on paper; most often it’s somewhere in between.

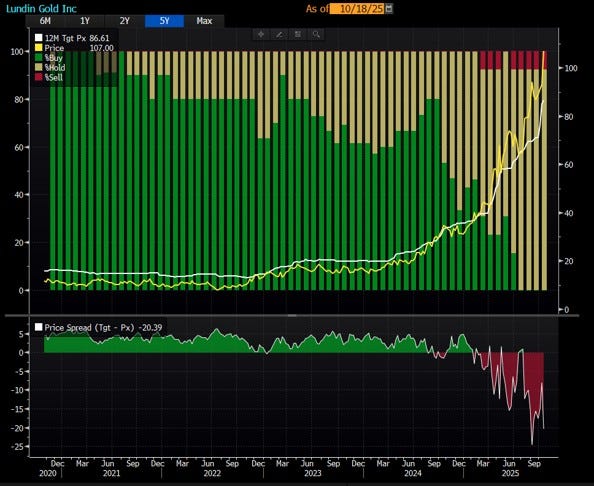

Unfortunately, many sell-siders are juniors fresh out of university—overwhelmed for the first couple of years—and they operate inside a culture that rewards herd behavior over independent thinking. Keep that in mind when you read their price targets (which I haven’t done in years). They struggle to think outside the box on gold and, in a rising tape, basically set targets to match the market. Groupthink at its finest. It’s a total waste of time.

Anyway, my value approach is not timid, as you will learn further down. Nor should it be—with a Latina supermodel. But it’s a shade more conservative than what I did at Alamos’s Island Gold, where we have a no-brainer growth track over five years and on-the-record guidance from John McCluskey. Here, we wait. The unicorn orebody makes the inferred feel borderline a no-brainer (hence the 9.4Moz in the model), but we’ll let the assays, not the adjectives, carry the rest of the day.

The range of outcomes is wide: Fruta del Norte could carry 9+ million ounces for years—if not decades—via steady year-by-year replacement; or the resources could peak in the next few years. What the drilling already suggests is that average grades aren’t improving the way they did at Island Gold—but tonnage (ore volume) may grow. Time will tell.

One last remark on exploration: you read our Alamos piece. You know what to look for on resource upside: continuity that scales, geometry that mines, competence that recovers, metre by metre.

That’s the essence of land optionality. FDN has the address. Now let the drill bit write the invitations. At the very least, near-mine results should keep replacing reserves for years to come, as 2024 already showed. Now let’s watch out when the first maiden resource for Bonza Sur is decleared.

Meanwhile, FDN isn’t just a geological unicorn, it’s an operational case study too.