K92 Mining - A Tier 1 Opportunity in the Making

A "Special Situation" in the Gold Mining Space

Why is K92 A Special Situation?

K92 is a scrappy operator’s masterclass.

Under John Lewins, a narrow-vein, undercapitalised asset that most misunderstood—Barrick included—has been turned into a high-margin growth engine through incremental geological intuition, focused exploration, careful engineering and disciplined reinvestment. Restarted in 2016 and declared commercial in 2018, it is no longer a promising teenager; it is a tier-one athlete hitting its stride.

What sets it apart is not a slide deck but a production profile and a cost base. K92 is moving into the 400,000 oz Au-equivalent class, with one of the lowest unit costs in our universe—thanks to a superior cost structure (grid power, access, paste backfill, mechanisation, geometry, labour costs, etc.) and copper and silver by-product credits that the market has barely priced.

This is also an execution story, not a promotion: grades and continuity in a “spaghetti soup” of veins—but really golden curtains, as I explain below—access opened and mechanised; and, crucially, the best near-mine resource endowment in our universe, much of it still to be declared as resource over the coming years by one of the largest exploration teams in gold mining. Huge.

All of that comes without financial leverage and with low operational gearing, courtesy of the superior cost structure. Just as important, the current growth leg carries minimal, if any development risk: the key expansion building blocks such as the new processing plant, paste plant and underground development access are already in place. Very special.

The kicker? John Lewins has executed this brownfield revival with the least equity dilution per ounce we know of. K92 may yet prove the most successful mining growth story—across commodities—with the lowest dilution per ounce produced from start to finish. A tier-one athlete on a value multiple, hiding in plain sight.

How Kainantu Found its Pulse Again

When K92 Mining bought the abandoned Kainantu mine from Barrick in 2014, the consideration was intentionally light up front and heavy on success: US$2m cash, a contingent US$60/oz on the first 1Moz produced, and a 2% NSR in Barrick’s favour. It was a classic “pay as you prove it” deal.

The original operation started construction in 2004 and came into production in 2006. Barrick acquired the mine in December 2007 from Highlands Pacific. Under Highlands, output was 27koz in 2006 and 32koz in 2007; under Barrick it managed a mere 10koz in 2008—69koz in total—before the mine was placed on care and maintenance in early 2009. Barrick’s rationale was straightforward: narrow-vein geometry and high operating costs made the mine uneconomic at prevailing gold prices.

Reading Barrick’s 2007 announcement with hindsight and the point is obvious: the acquisition was never really about the struggling mine; it was about the 2,900 km² land position.

By 2015, when John Lewins and team took over, Kainantu wasn’t a turnaround so much as a rescue—albeit one with roughly US$100m of sunk development to access Irumafimpa and Kora and a small processing plant. After seven years of care and maintenance, the tunnels were flooded, the plant was idle, and the highlands jungle had begun to reclaim the site. Not an easy brownfield set-up.

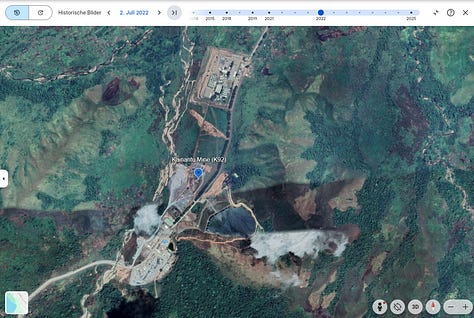

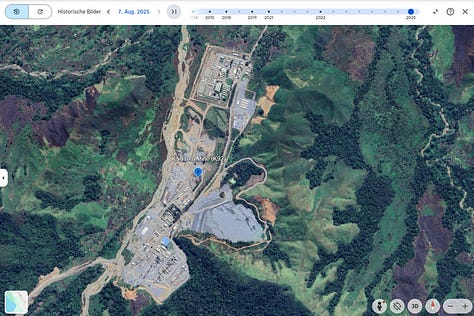

Before the details, look at the site yourself: three Google Earth history screenshots (September 2015, July 2022 and August 2025) tell the story of a mine being brought back to life.

What looked like failure to a major with a 30,000-foot portfolio view in 2009 was opportunity to a team that understood how to treat a small, high-grade system. A firmer gold backdrop helped: gold averaged US$1,160 in 2015, US$1,393 in 2019, then broke out to US$1,770 in 2020.

Crucially, the government renewed Mining Lease ML150 and no state equity was imposed. Kainantu carries no 10% free-carried interest at the mine or company level. Papua New Guinea participates via royalties and taxes, not share ownership: a 2% royalty (NSR/FOB basis), the 0.5% MRA levy on mine revenue, and 30% income tax, alongside landowner agreements.

Important Risk Assessment:

The statutory right for the State to take an equity stake can apply to new mining leases in Papua New Guinea, but K92’s current ML150 carries no such provision. Politically, alignment still comes from operating performance, stable relationships and benefits flowing to landowners—not from a carried interest. But a possible development of Blue Lake within the Exploration Licence 470 (EL 470) may change that conversation. Also, to our knowledge there is no Standstill Agreement in place to legally protect (in practice everything can change) the current status quo, similar to Fruta del Norte, for example.

Geological Comparison

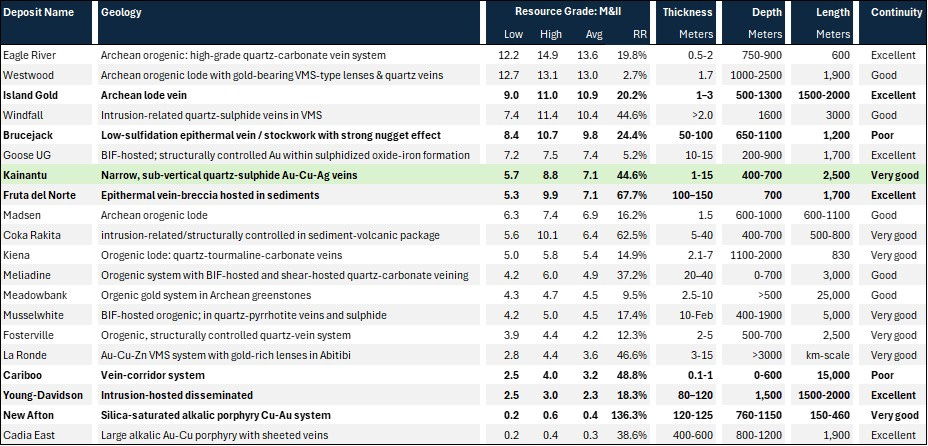

Before drilling into Kainantu’s operation, it helps to anchor the deposit against the underground case studies we have already covered—Island Gold, Young-Davidson and Fruta del Norte—using the same simple comparison table to keep the contrasts sharp.

Kainantu is a high-grade, narrow-vein epithermal system with pronounced variability in thickness both between and within the principal lodes, yet with consistently very good continuity along strike and down dip. In round numbers, working widths sit in the narrow-to-moderate camp, with true thickness commonly in the 1–15 meters range and resource grades in the mid-to-high single digits for gold.

That geometry puts Kainantu near to the Island Gold deposit, not bulk-tonnage underground archetypes: not as high-grading as the best Island Gold panels, but generally thicker and with comparable continuity—exactly the sort of profile that matters for stope design, dilution control and mine scheduling.

Set against Young-Davidson, the differences are first principles. Young-Davidson lives on volume rather than grade: orebody thickness on the order of 80–120 meters enables bulk mining at low single-digit grades, a strategy that optimises unit costs through scale but depends on sheer tonnes moved.

Kainantu extracts value through selectivity. Mining widths are measured in metres, not tens of metres; production leans on long-hole stoping and cut-and-fill to preserve head grade and contain dilution; development is targeted to chase discrete, steeply dipping lodes rather than to sweep a broad, homogeneous panel. It is a different cost and risk equation.

Fruta del Norte, by contrast, is the unicorn that combines thickness with high grade and excellent continuity. A deposit capable of 100–150 meter mining widths while still carrying resource grades around 7g/t for gold is rare, and it compresses both operating and capital intensity per ounce. Kainantu cannot claim that blend of bulk width and high grade; what it does have is a disciplined narrow-vein architecture that delivers continuity over kilometres of strike, allowing value to compound by repeating well-understood stoping patterns at scale.

The Golden Curtains of Kainantu

When geologists speak of a narrow-vein system, most of us non-geologists instinctively picture our own human blood vessels — thin, branching, fragile. At least that’s what happens in what Daniel Kahneman calls System 1 in his brilliant book Thinking, Fast and Slow: when certain words are spoken, intuition takes over.

But in this case, intuition deceives us. That mental picture is a misleading one as it doesn’t do this geological system any justice. The “narrow veins” of the Kainantu Mine — the Kora and Judd systems — are not fine threads of gold, but rather steep, towering curtains of quartz, sulphides, and metal running deep through the mountain.

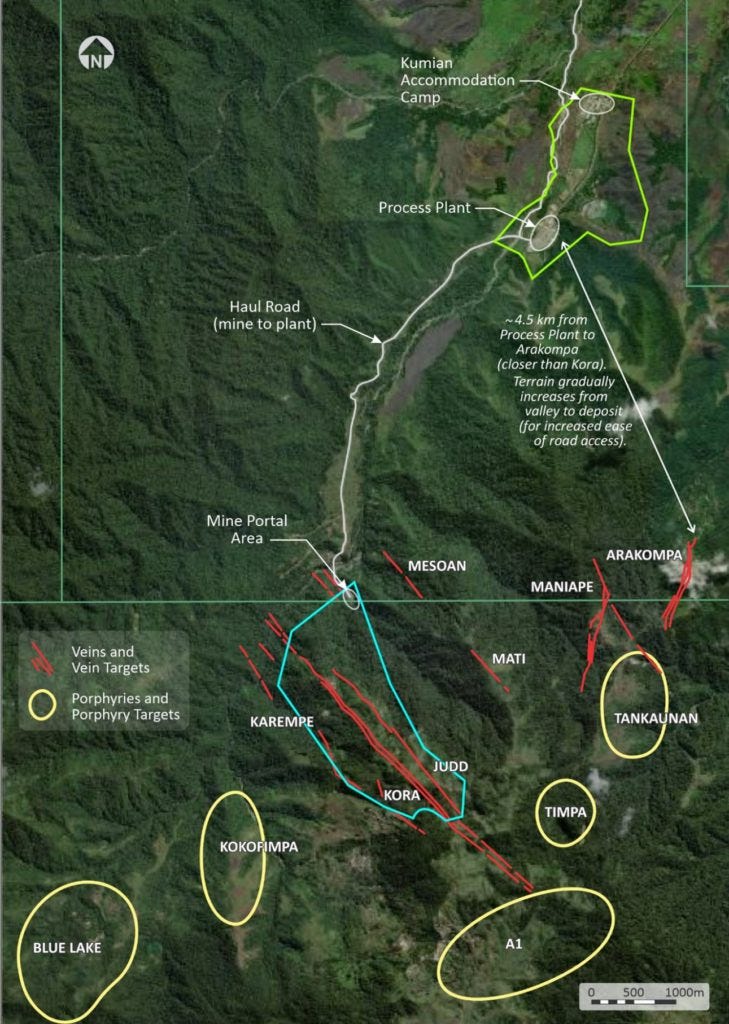

Technically, the term narrow-vein system is of course correct. But “narrow” refers only to thickness — typically one to fifteen metres wide. Imagine a bird, or avatar with laser vision, flying over the Kainantu mountainous region able to look through solid rock. From his vantage point high above, he would see two glowing lines buried in stone — perhaps like spaghetti laid out beneath the surface.

These “spaghetti” (lines in red above) would be astonishingly long — literally kilometres in what geologists call strike length (strike, by the way, has nothing to do with labour disputes or lightning bolts here, more with a poorly developed English vocabulary). Our laser-eyed avatar would see these narrow veins stretching for two to three kilometres, their thickness expanding and contracting from one to fifteen metres as they undulate through the rock. Huge dimentions.

But the real beauty of Kainantu would only reveal itself to our avatar if he could slice the mountain open into its cross section like a cake, right along the lines of those veins. Inside, he would find mineralized curtains of gold, copper, silver, and quartz hanging down for hundreds of metres — what geologists call their vertical extent (or down dip). Johan Wolfgang Goethe wouldn’t approve of such simple words, but it is what it is.

So don’t imagine tangled spaghetti in stone. Imagine instead long, folded golden curtains, descending vertically through the crust — continuous lodes where mineral-rich fluids once surged upward, cooled, and crystallized. In some places, these curtains swell — forming dilatant zones, where the rock cracked a little wider and trapped more quartz, sulphides, and gold. Those are the rich pockets — the geological knots of fortune, with a mix of gold and copper clitter.

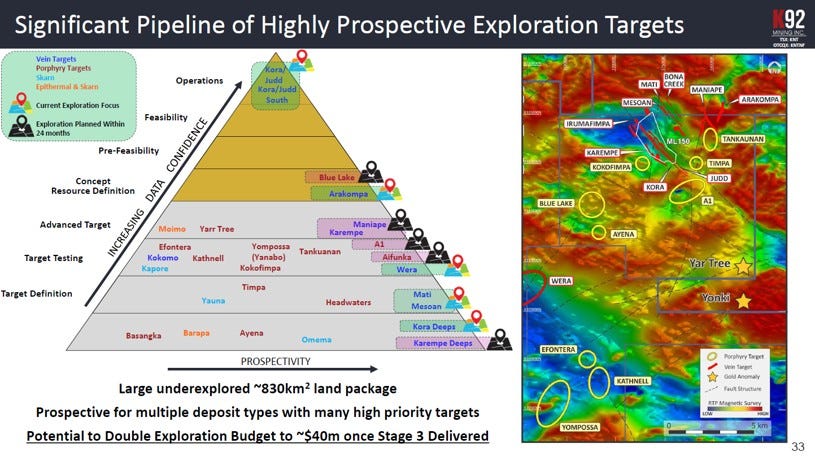

Kora and Judd run side by side, like twin arteries of an ancient geological heart, shaped by the same tectonic rhythm and fed by the same molten pulse. Nor is it a two-vein curtain of Kora and Judd. The 2024 technical report sets out at least nine other golden curtain siblings: Judd (including Judd South), Kora (including Kora South), Karempe, Irumafimpa (Barrick’s original production target), Mesoan, Mati, Bona Creek, Maniape and Arakompa. That is the visible family; the geophysics hints at more.

This breadth flows from John Lewins’s pragmatic approach to exploration. When he and his team reopened the mine from Barrick in 2017, they did not declare reserves. They kept disclosure at resources, fully aware that spending scarce capital to engineer reserves in a narrow-vein system—before underground access and close-spaced drilling—would waste time and money to appease generalists who would not grasp the geometry anyway.

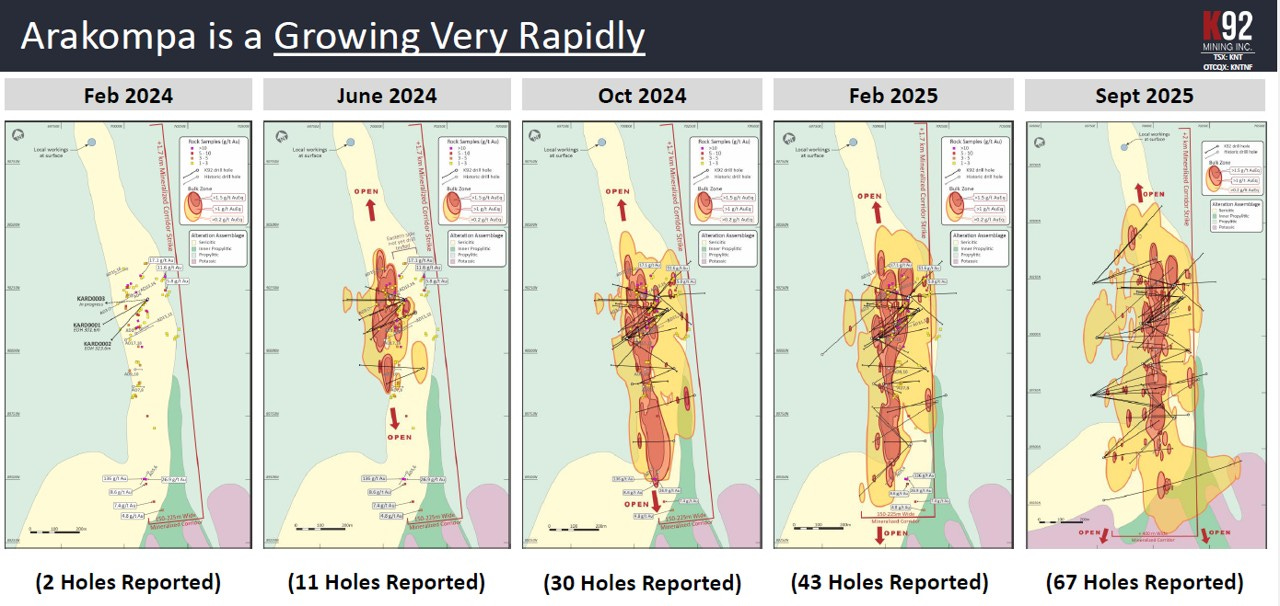

Instead, they restarted with limited but well-aligned capital and a clear aim: let production fund exploration. Cash flow has since underwritten the drill-out of multiple targets, with Arakompa the current standout—growing rapidly and not yet even a declared resource. The company will bring in two more surface diamond rigs to arrive in late Q4 2025, supporting a significant ramp-up in its exploration. That is land optionality at work: acquire a district, open the cash register and let geology compound. It is, within the rules, the clean way for you to front-run Wall Street too.

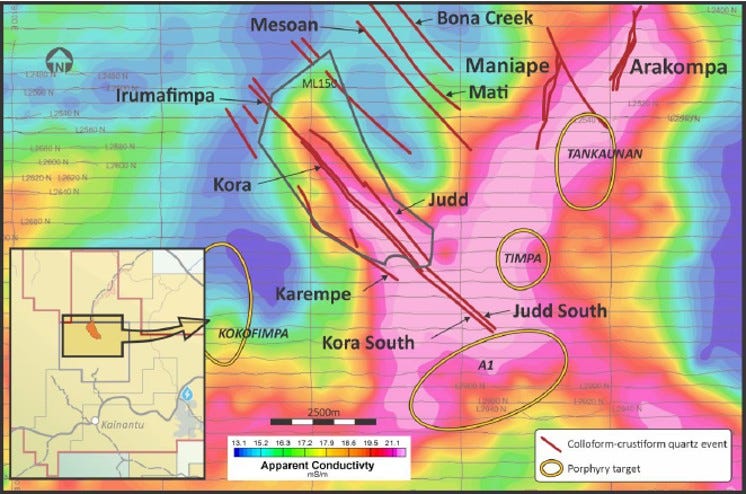

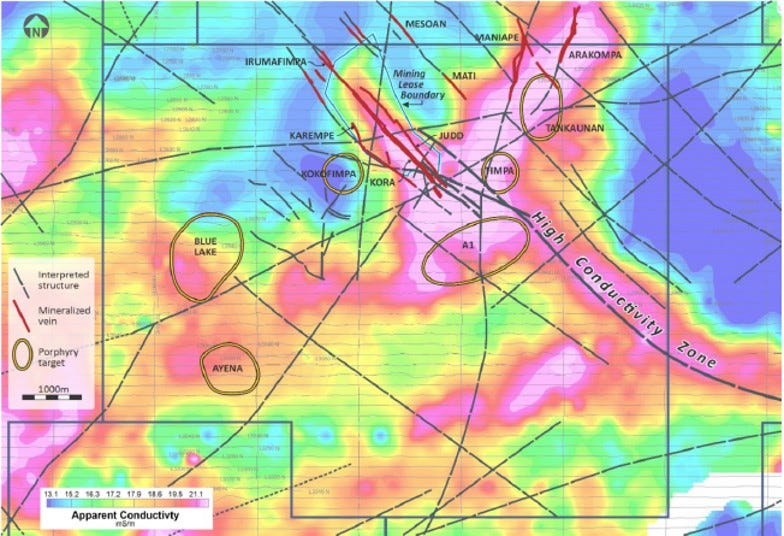

The menu is already a small but excellent meal—and it gets better. The technical report points to the likely price of this spaghetti soup, and it is large. A helicopter-borne electromagnetic survey, flown in November 2021 by Expert Geophysics Limited, mapped the property at depth and outlined it in a technical report. The programme delivered a far greater depth range than was technologically possible before. Think of it as geology’s analogue to improved seismic tech in oil and gas: higher fidelity, deeper penetration, better targeting. In short, a sharper, bigger image where a smaller, blurred one once stood.

Data were collected along east–west lines nominally spaced at 200 metres, with north–south tie lines at 2,000 metres. The conductivity maps light up the known lodes and, more importantly, illuminate many more noodles plus a few likely bolognese pots. The grey “interpreted structures” (below in grey) are new spaghetti strands yet to be drilled and potentially converted into resources, and there are loads of them. The yellow-circled zones mark porphyry targets—the sauce. We will return to those.

The 2024 report says it plainly. The airborne deep-penetrating geophysics over the entire property shows strong correlation between known deposits and conductive bodies. A swathe of high Apparent Conductivity extends from Kora and Judd into EL470 for several kilometres, and a longitudinal section shows the same highly conductive corridor north and south of the Kora mining centre.

The conclusion is unambiguous: there is extensive untested strike potential to the Kora–Kora South and Judd–Judd South vein systems beyond the A1 porphyry to the south-east for several kilometres. The programme also identifies new vein and porphyry targets on K92’s licences and highlights known mineralised porphyries, including A1, Blue Lake, Tankaunan and Timpa.

Now let that settle and glance at the reserve and resource table for Judd and Kora alone. Gold resources and reserves for those two veins total 6.38 Moz. Add silver and copper and the package equates to 8.8Moz AuEq, supporting a 27-year life at 240,000oz per annum, which the company is set to deliver from 2026. These veins are not bounded; both remain open at depth and are likely to lengthen as development advances and provides ever cheaper underground drill platforms. That is how narrow-vein systems behave when the lodes are continuous and the structure is coherent.

Now layer in the rest of the vein systems already mapped—and the additional structures now outlined by geophysics—and the size of the prize comes into view. The district potential is very large. A 20Moz gold endowment or more is within reasonable geological expectation.

Have I misplaced my marbles? Hardly. The number is defendable. A 20Moz district endowment sits well within reasonable geological expectation—strictly as an exploration target, not a resource—and the distinction matters. Here is the sanity check, built only from what we can see and measure today.

Sanity Check

Kora and Judd together carry 30.8 Mt at 6.44 g/t for 6.38 Moz of gold as at 1 January 2024. Those two veins occupy roughly 2.5 km of strike and a few hundred metres of vertical extent. The MobileMT maps show the same conductive corridor continuing for several kilometres beyond A1 to the south-east and back to the north, with multiple parallel structures already mapped and several more interpreted. If you simply scale for strike length alone—say, from a mined-and-drilled 2.5 km to an explored corridor of 8–10 km—you get a factor of three to four on tonnage potential before touching thickness or the count of spaghetti strands. Keep grades constant for the thought experiment and you are already in the right postcode.

At today’s tenor, 20 Moz of gold requires on the order of 90–105 Mt of mineralised material at 6–7 g/t. Kora+Judd provide 30.8 Mt of that number. The remaining 60–75 Mt would need to come from the rest of the vein family—Arakompa, Mesoan, Mati, Maniape, Bona Creek, Karempe, Irumafimpa and their interpreted siblings—plus depth extensions on Kora and Judd as development pushes the drill horizons down. The footprint shown by the conductivity panels is big enough to host that quantum if even a subset of those structures prove up with Kora-like geometry and grade. Arakompa’s rapid growth on sparse early drilling is exactly the sort of behaviour you want to see if you are trying to justify that leap from a two-vein mine to a district.

None of this is a compliant estimate, and it should not be read as one. Conductive trends are not the same as ore, porphyry “sauce” is not the same as narrow-vein “noodles”, and continuity can fray where structures get messy. Nor would I value it as intrinsic to the company. But if you take the measured 6.38Moz from two veins over 2.5km, lay that across a corridor three to four times longer with a larger set of parallel lodes, and assume the mine keeps doing what narrow-vein systems do when you give them access and drill bays, a 20Moz district endowment is not a boast; it is an upside case à la “Pierre Lassonde school of thought”. That, in essence, is what the maps, sections and drill plots are signalling: the image has gone from small and blurred to sharper and larger, and the pasta bowl looks far from empty.

Time will decide what the drill bit delivers, but the investment point is balance. Geologists are paid to be conservative; their craft is humility before geology, because Mother Nature punishes hubris without appeal. At the other pole sit the Silicon Valley promoters—Elon, Cathie and friends—who can conjure trillion-dollar valuations from a sketch and a slide on “TAM expansion”. Hand them land optionality and they would price Kainantu at 100 Moz booked by tomorrow morning. Neither instinct serves capital well. Too conservative and you rack up silent opportunity cost; too promotional and you incinerate cash.

In my humble opinion, our job as resource investors is to sit between those extremes: recognise that land optionality has real, compounding value when the geology is predisposed; insist on disciplined capital allocation and let production pay for proof; refuse to badge exploration upside as reserves or resources until the drill core says so; but allocate capital where land optionality is waiting to happen. Then let time be your friend and invest for the long term. Find a few of those and take a holiday.

This series began with Alamos Gold for a reason, and K92’s spaghetti soup earns its place on the table precisely because it rewards patience without requiring faith. And no, three elephants in a row — those being Alamos, Lundin Gold and now K92 — does not mean they’re as common as mice — you won’t find them on every corner. What you do get in this Substack is the benefit of my pre-selection. If this work proves useful, I’d be grateful if you shared it with a few like-minded investors; it helps justify the time it takes to do it properly.