Resource Scarcity Defines the Tipping Point, Not the Strategy

Lesson 4

Lesson 4: Scarcity Defines the Tipping Point, Not the Strategy

The idea of using economic pressure to influence the outcome of war is hardly modern. By the early 19th century, elaborate strategies already existed to shape military conflicts through economic disruption.

One of the most striking early examples was Napoleon’s Continental Blockade, which aimed to undermine Britain’s maritime dominance and force London into a peace settlement on French terms. But the strategy backfired. British merchants perfected smuggling routes, and Napoleon’s efforts to enforce the blockade led to military overstretch, including the disastrous invasions of Spain and Portugal. That campaign gave birth to the modern concept of guerrilla warfare—a “small war” fought with relentless brutality. Yet despite the hardship it inflicted, the blockade failed to deliver peace.

World War II offers even more powerful illustrations of this principle. Germany’s U-boat campaign in the Atlantic—its attempt to starve Britain of supplies from the United States—initially enjoyed significant success. At its peak in 1942, German submarines were sinking Allied tonnage faster than it could be replaced. But the tide turned. Thanks to technological innovations like convoy systems, long-range patrol aircraft, and, crucially, the breaking of the Enigma code by British genius Alan Turing and his team at Bletchley Park (movie “The Imitation Game”), Allies Forces gained the upper hand. German U-boat losses spiked, and the strategy collapsed. But rather than admit defeat or shift course, the Nazi leadership clung to increasingly irrational hopes of technological breakthroughs or race supremacy.

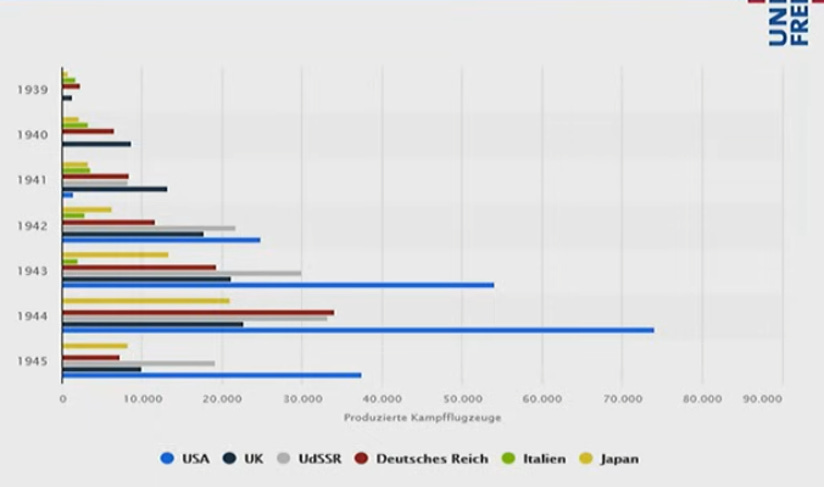

This kind of denial was not limited to the sea. Looking at aircraft production figures alone, it becomes clear that Germany had already lost critical ground to Allied forces long before the Battle of Stalingrad (July 1942 – February 1943). The resource imbalance was becoming overwhelming. Yet rather than interpret these trends as a signal for negotiation or retreat, Hitler and his command circle doubled down. They reinterpreted production statistics ideologically, fueling the dream of a Siegfrieden—a “victorious peace” that would justify continued sacrifice.

Here lies an important lesson of modern wars: political leaders often continue to fight, especially toward the end, not based on material resources, but on national myths, ideological narratives, psychological endurance, or other collective virtues. Both the Germans and the Japanese invoked the fighting spirit and the perseverance of their soldiers in World War 2 (remember Hiroo Onoda?). The Viet Cong did the same during the Vietnam war.

It is not the objective availability of resources that determines the outcome, but the perceived resilience and staying power of societies — or what their political leaders convince themselves of.