Grasberg: Why the World’s Wettest Block Cave Mine May Never Restart?

Freeport’s Grasberg Copper Gold Mine: More than “Force Majeure”…!

Freeport has declared force majeure at Grasberg — and with good reason.

This will shake both copper and gold balances. Let me explain why.

Grasberg: a Giant

Grasberg is one of the largest mines on earth, producing roughly 1.7 billion pounds of copper (≈2% of global supply) and 1.6 million ounces of gold annually (≈1.5% of global supply).

Think of it as a vast underground city: 28,000 employees, 250 kilometers of tunnels across dozens of levels. Each year, another 35–40 kilometers are added — about the length of Switzerland’s Gotthard Base Tunnel, the world’s longest rail tunnel.

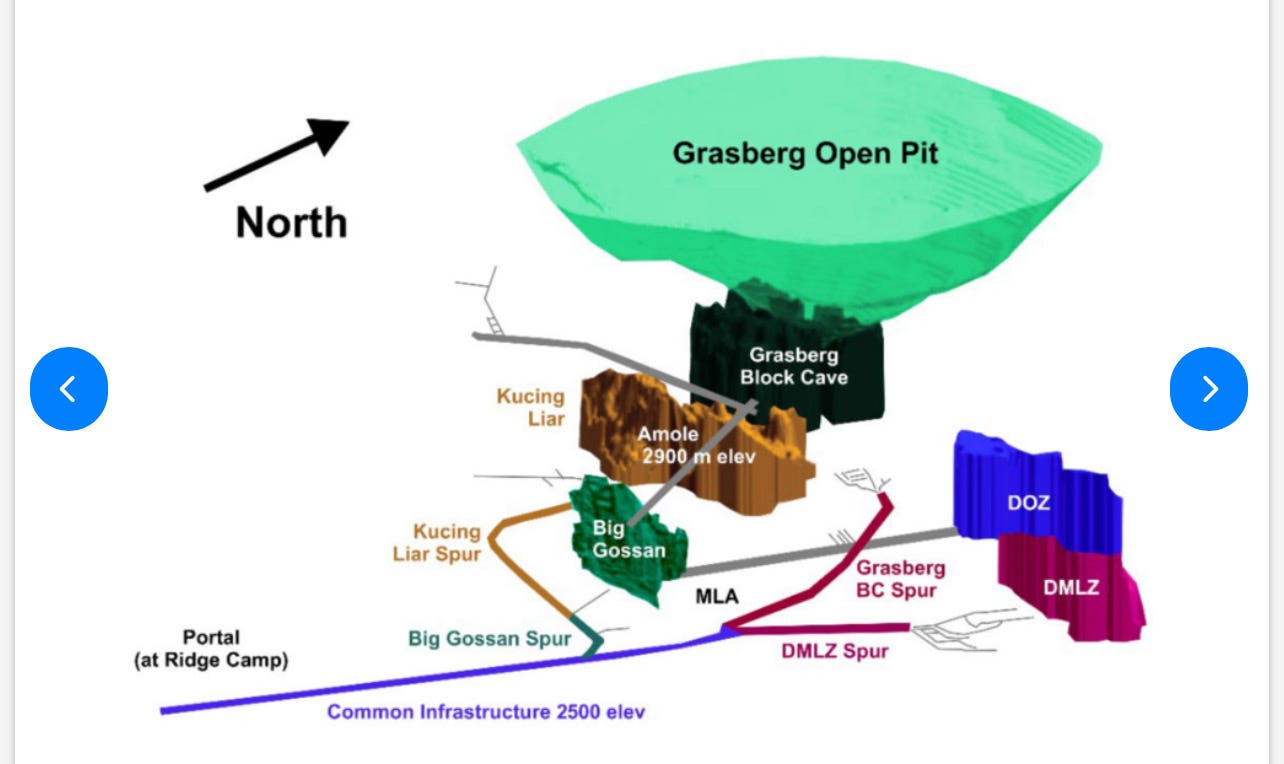

At its heart lies the Grasberg Block Cave (GBC), accounting for about 70% of reserves and output. Other sections include Big Gossan and Deep MLZ.

Ore bodies in Grasberg Block Cave Mine. There are five existing blocks in the Grasberg Block Cave Mine, i.e., Grasberg Block Cave, Kucing Liar, Big Gossan, DOZ, DMLZ. Each block is accessed through a spur towards the Portal at Ridge Camp.

Disaster Struck

On September 8, disaster struck: roughly 800,000 tons of wet material suddenly rushed in, flooding multiple underground levels. The mud hit GBC directly — the very core of Grasberg’s production.

A catastrophic failure. How was this even possible?

Here is a clip. The stuff of nightmares

Block Caving: Rare and Risky

Block caving itself may become central to the story. Out of more than 12,000 active mines worldwide, only about 20–25 have ever used block caving. Today, fewer than ten are active. That’s <0.1% of all mines.

It is an exceptionally rare method, reserved for very large, low-grade underground ore bodies, which themselves are scarce. Most mines use open-pit, stoping, or cut-and-fill.

The economic appeal of block caving is obvious — very low cost per ton. But the geotechnical risks are immense. Once caving starts, the process is essentially an engineered collapse of the mountain. What could possibly go wrong?

The Climate Dimension

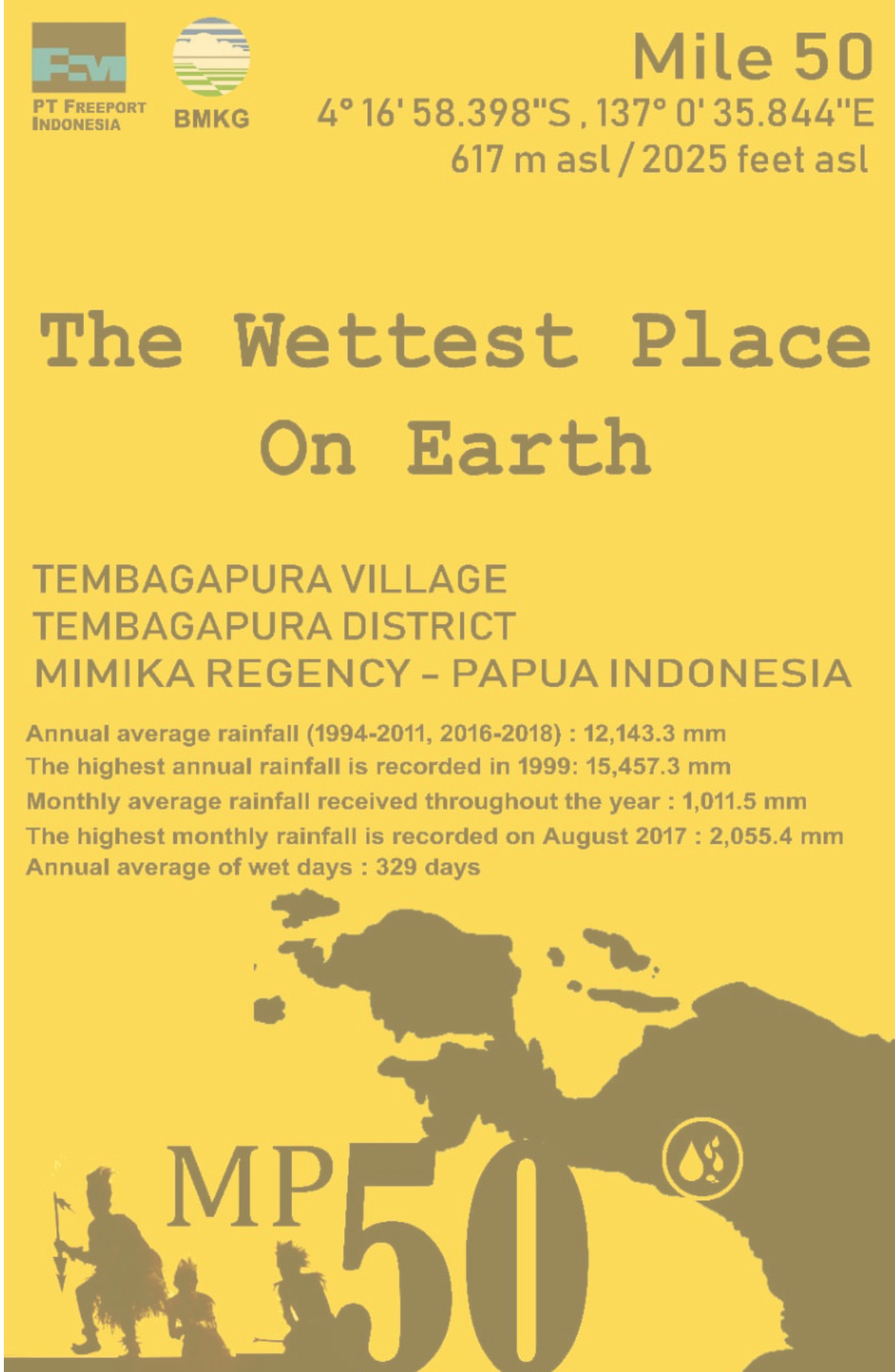

Grasberg doesn’t just face block caving risk — it faces it in one of the wettest places on earth.

The mine site and access road receive around 12 meters of rainfall per year, with rain on about 330 days annually. Papua often records monthly peaks above 2 meters. And remember: Grasberg is high in the mountains.

Compare this to El Teniente in Chile, the world’s largest underground copper mine, also a block cave. Its “normal” rainfall? About half a meter annually. Same method, completely different hydrological setting. And Chile is not tropical humid — infiltration and groundwater pressure risks are fundamentally lower.

Wet muck is a known risk even in Chile’s dry climate. In Papua’s rainfall regime, the risk should be an order of magnitude higher.

Wet Muck: The Nightmare Failure Mode

When water infiltrates a block cave, broken rock can turn into a dense slurry — wet muck — that suddenly rushes into tunnels. It is one of the most feared failure modes underground. And it appears to be what happened at Grasberg.

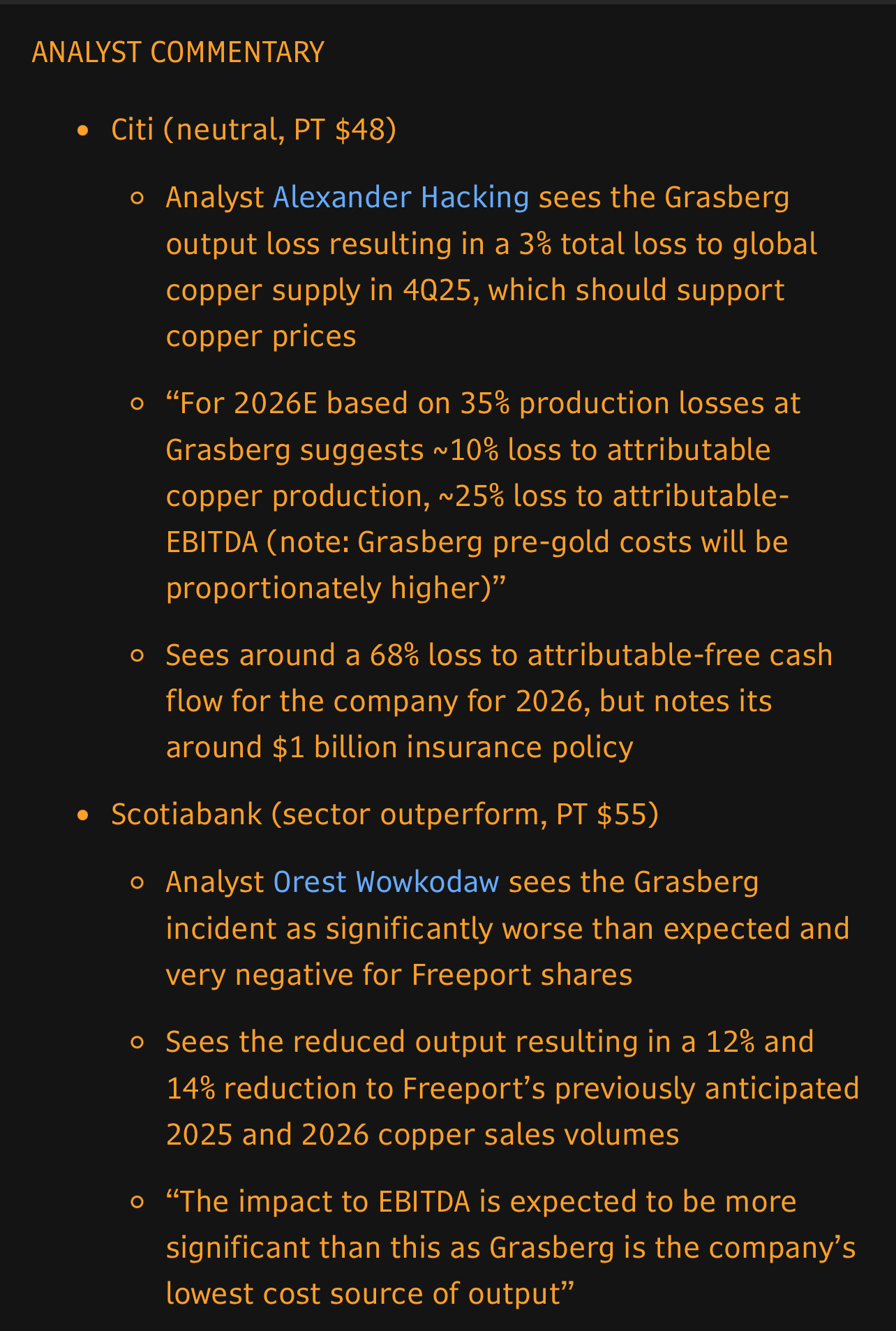

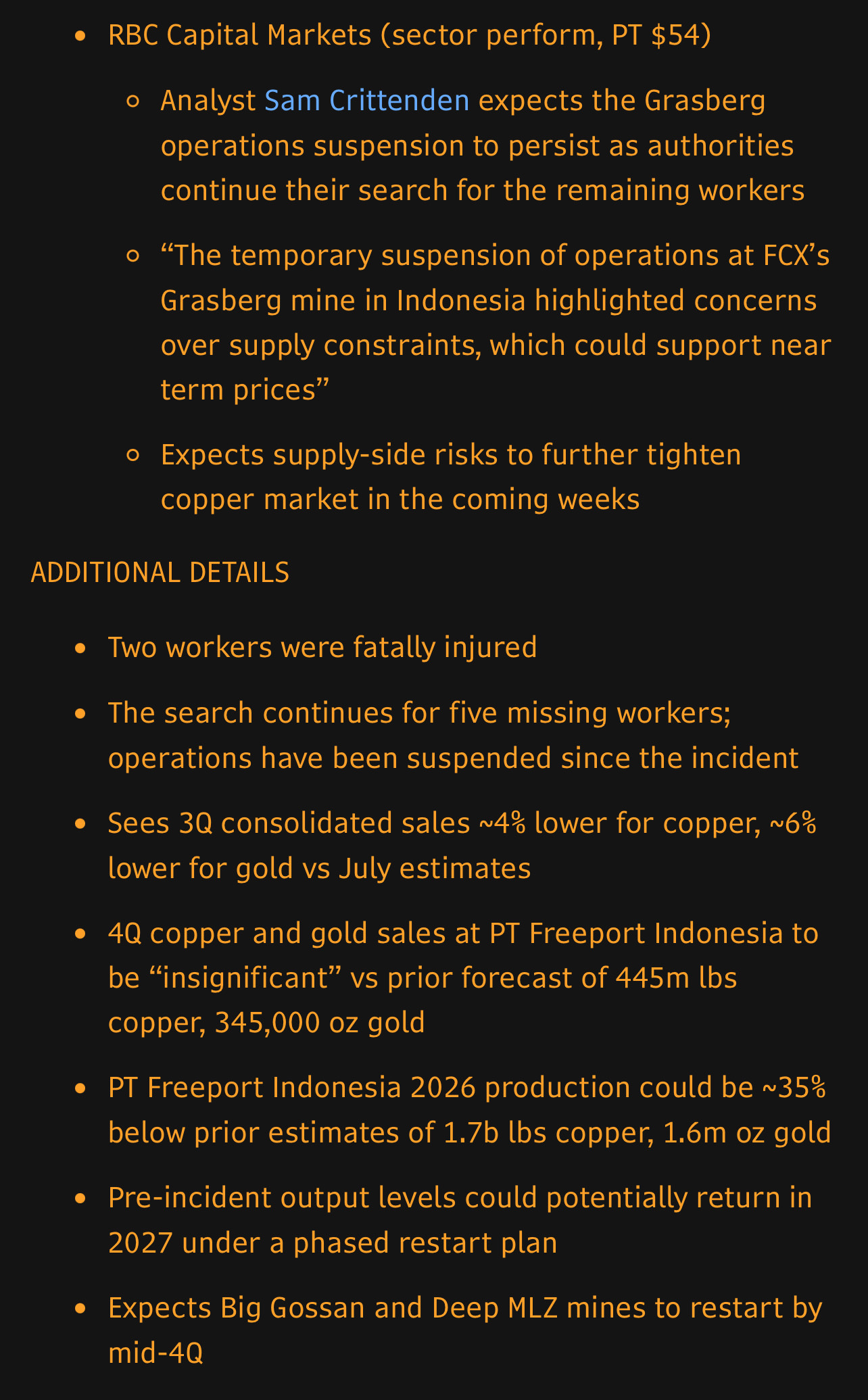

Yet what are analysts saying? Everyone parrots “force majeure” and “back by 2027.” Why is wet muck risk missing from the conversation?